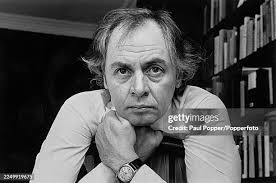

(Gettyimages.com)

“They will try and cure us. Maybe they will succeed. There’s still hope that they will fail.”

–R.D. Laing in The Politics of Experience

R. D. Laing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Ronald David Laing | |

|---|---|

| Laing in 1983, perusing The Ashley Book of Knots (1944) | |

| Born | Ronald David Laing 7 October 1927 Govanhill, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | 23 August 1989 (aged 61) Saint-Tropez, France |

| Known for | Medical model |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Hearne(m. 1952; div. 1966) Jutta Werner(m. 1974; div. 1986) |

| Children | 10 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

Ronald David Laing (7 October 1927 – 23 August 1989), usually cited as R. D. Laing, was a British psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness, particularly psychosis and schizophrenia.[1]

Laing’s views on the causes and treatment of psychopathological phenomena were influenced by his study of existential philosophy and ran counter to the chemical and electroshock methods that had become psychiatric orthodoxy. Laing took the expressed feelings of the individual patient or client as valid descriptions of personal experience rather than simply as symptoms of mental illness. Though associated in the public mind with the anti-psychiatry movement, he rejected the label.[2] Laing regarded schizophrenia as the normal psychological adjustment to a dysfunctional social context.[3]

Politically, Laing was regarded as a thinker of the New Left. He has been theatrically portrayed by Mike Maran, Alan Cox, Billy Mack and by David Tennant in the 2017 film Mad to Be Normal.

Early years

Laing was born in the Govanhill district of Glasgow on 7 October 1927, the only child of civil engineer David Park MacNair Laing and Amelia Glen Laing (née Kirkwood).[4] Laing described his parents — his mother especially — as being somewhat anti-social, and demanding the maximum achievement from him. Adrian, his biographer son discounted much of Laing’s published childhood account, and an obituary by an acquaintance of Laing asserted that about his parents – “the full truth he told only to a few close friends”.[5][6]

He was educated initially at Sir John Neilson Cuthbertson Public School and after four years transferred to Hutchesons’ Grammar School. Described variously as clever, competitive or precocious, he studied classics, particularly philosophy, including through reading books from the local library. Small and slightly built, Laing participated in distance running; he was also a musician, being made an Associate of the Royal College of Music. He studied medicine at the University of Glasgow. During his time in Glasgow, he set up a “Socratic Club”, of which the philosopher Bertrand Russell agreed to be president. Laing failed his final exams. In a partial autobiography, Wisdom, Madness and Folly, Laing said he felt remarks he made under the influence of alcohol at a university function had offended the staff and led to him being failed on every subject including some he was sure he had passed. After spending six months working in a psychiatric unit, Laing passed the re-sits in 1951 to qualify as a medical doctor.[7]

Career

Laing spent a couple of years as a psychiatrist in the British Army Psychiatric Unit at Netley, where, as he later recalled, those trying to fake schizophrenia to get a lifelong disability pension were likely to get more than they had bargained for as insulin shock therapy was being used.[8] In 1953, Laing returned to Glasgow, participated in an existentialism-oriented discussion group, and worked at the Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital.[9] The hospital was influenced by David Henderson‘s school of thought, which may have exerted an unacknowledged influence on Laing; he became the youngest consultant in the country.[10][7] Laing’s colleagues characterised him as “conservative” for his opposition to electroconvulsive therapy and the new drugs that were being introduced.[10]

In 1956, Laing went to train on a grant at the Tavistock Clinic in London, widely known as a centre for the study and practice of psychotherapy (particularly psychoanalysis). At this time, he was associated with John Bowlby, D. W. Winnicott and Charles Rycroft. He remained at the Tavistock Clinic until 1964.[11]

In 1965, Laing and a group of colleagues created the Philadelphia Association and started a psychiatric community project at Kingsley Hall, where patients and therapists lived together.[12] The Norwegian author Axel Jensen contacted Laing at Kingsley Hall after reading his book The Divided Self, which had been given to him by Noel Cobb. Laing treated Jensen, and subsequently, they became close friends. Laing often visited Jensen on board his ship Shanti Devi, which was his home in Stockholm.[13]

In 1967, Laing appeared on the BBC programme Your Witness, chaired by Ludovic Kennedy, on which, alongside Jonathan Aitken and G.P. Ian Dunbar, he argued for the legalisation of cannabis in the first live television debate on the subject.[14] In the same years, his views were explored in the television play In Two Minds, written by David Mercer.

In October 1972, Laing met Arthur Janov, author of the popular book The Primal Scream. Although Laing found Janov modest and unassuming, he considered him a “jig man” (someone who knows a lot about a little). Laing sympathized with Janov but regarded his primal therapy as a lucrative business—one which required no more than obtaining a suitable space and letting people “hang it all out”.[15]

Inspired by the work of American psychotherapist Elizabeth Fehr, Laing began to develop a team offering “rebirthing workshops” in which one designated person chooses to re-experience the struggle of trying to break out of the birth canal represented by the remaining members of the group who surround him or her.[16] Many former colleagues regarded him as a brilliant mind gone wrong.

Laing and anti-psychiatry

Laing was seen as an important figure in the anti-psychiatry movement, along with David Cooper, although he never denied the value of treating mental distress.

If the human race survives, future men will, I suspect, look back on our enlightened epoch as a veritable age of Darkness. They will presumably be able to savour the irony of the situation with more amusement than we can extract from it. The laugh’s on us. They will see that what we call “schizophrenia” was one of the forms in which, often through quite ordinary people, the light began to break through the cracks in our all-too-closed minds.

R.D. Laing, The Politics of Experience, p. 107

He also challenged psychiatric diagnosis itself, arguing that the diagnosis of a mental disorder contradicted accepted medical procedure: the diagnosis was made on the basis of behaviour or conduct of an examination and ancillary tests that traditionally precede the diagnosis of viable pathologies (like broken bones or pneumonia) occurred after the diagnosis of mental disorder (if at all). Hence, according to Laing, psychiatry was founded on a false epistemology: illness diagnosed by conduct but treated biologically.

Laing maintained that schizophrenia was “a theory not a fact”; he believed leading medical geneticists did not accept the models of genetically inherited schizophrenia being promoted by biologically based psychiatry.[17] He rejected the “medical model of mental illness“—according to Laing, diagnosis of mental illness did not follow a traditional medical model—and this led him to question the use of medication such as antipsychotics by psychiatry. His attitude to recreational drugs was quite different; privately, he advocated an anarchy of experience.[18]

Politically, Laing was regarded as a thinker of the New Left.[19]