NOVA PBS Official Dec 22, 2025 Discovering dark energy wasn’t just thrilling—it was terrifying. Nobel Prize Winner Adam Riess explains the nerve-wracking process behind confirming that the universe’s expansion is accelerating and why Einstein’s so-called “biggest blunder” turned out to be anything but. ????️ Watch the full podcast: • Interview: Discovering Dark Energy and the… Adam Riess is an astrophysicist, professor at Johns Hopkins University, and a distinguished astronomer at Space Telescope Science Institute. In 2011, he was named as a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the discovery that the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating. Since then he has continued refining measurements of cosmic expansion and the Hubble constant, aiming to find and measure the most distant type Ia supernovae known, to probe the origin of cosmic acceleration. “Particles of Thought” is hosted by Hakeem Oluseyi, an astrophysicist, author, STEM educator, multi-patented inventor, science journalist, TV personality, science communicator, and inspirational speaker. His research is based on “hacking stars” to understand our universe better and develop innovative new technologies. Oluseyi’s work has resulted in 11 patents and more than 100 publications covering contributions to astrophysics, cosmology, and plasma physics and the development of space missions, observatories, focal plane instruments, detectors, semiconductor manufacturing, and ion propulsion.

Millais: Christ in the House of His Parents

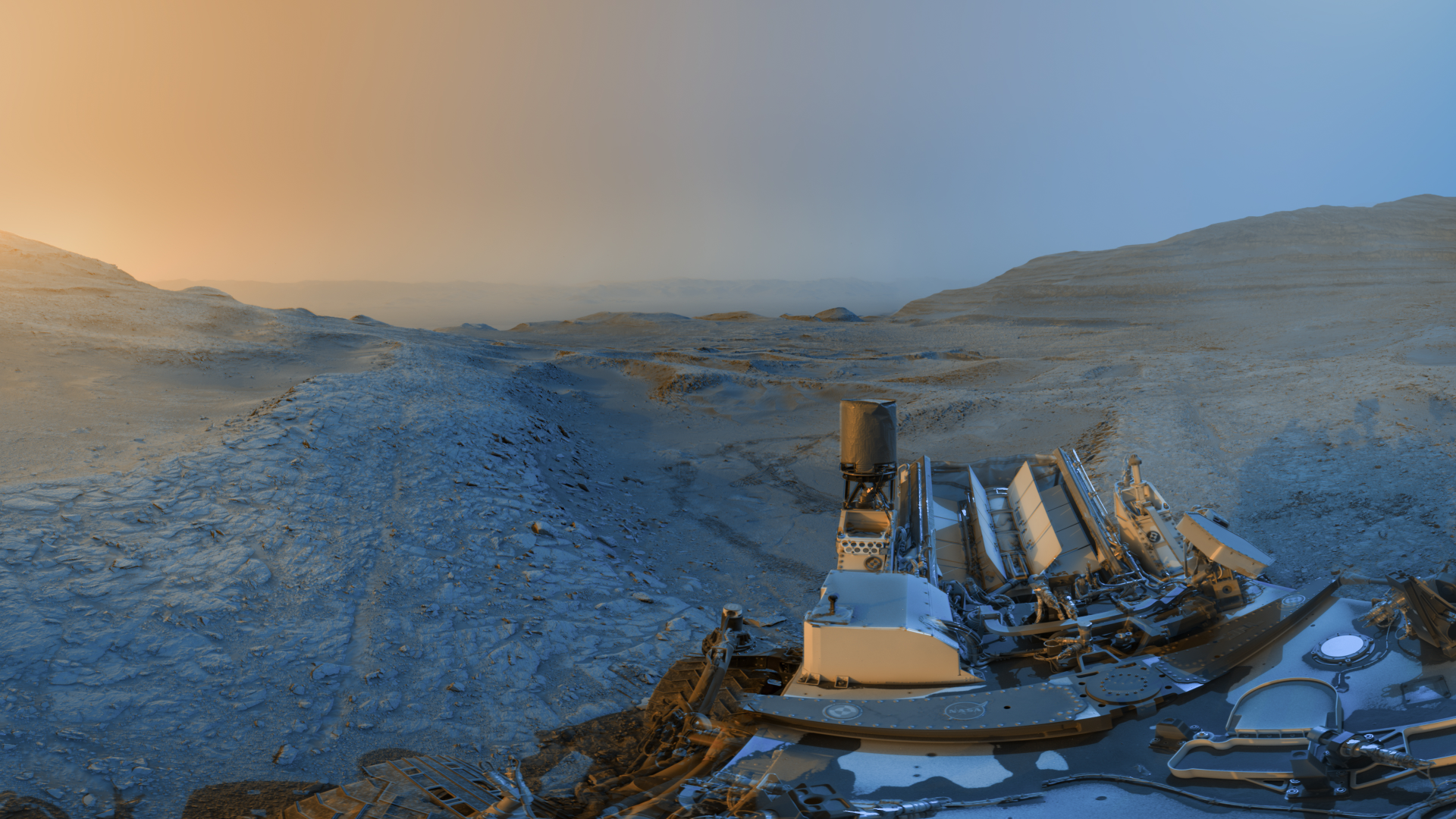

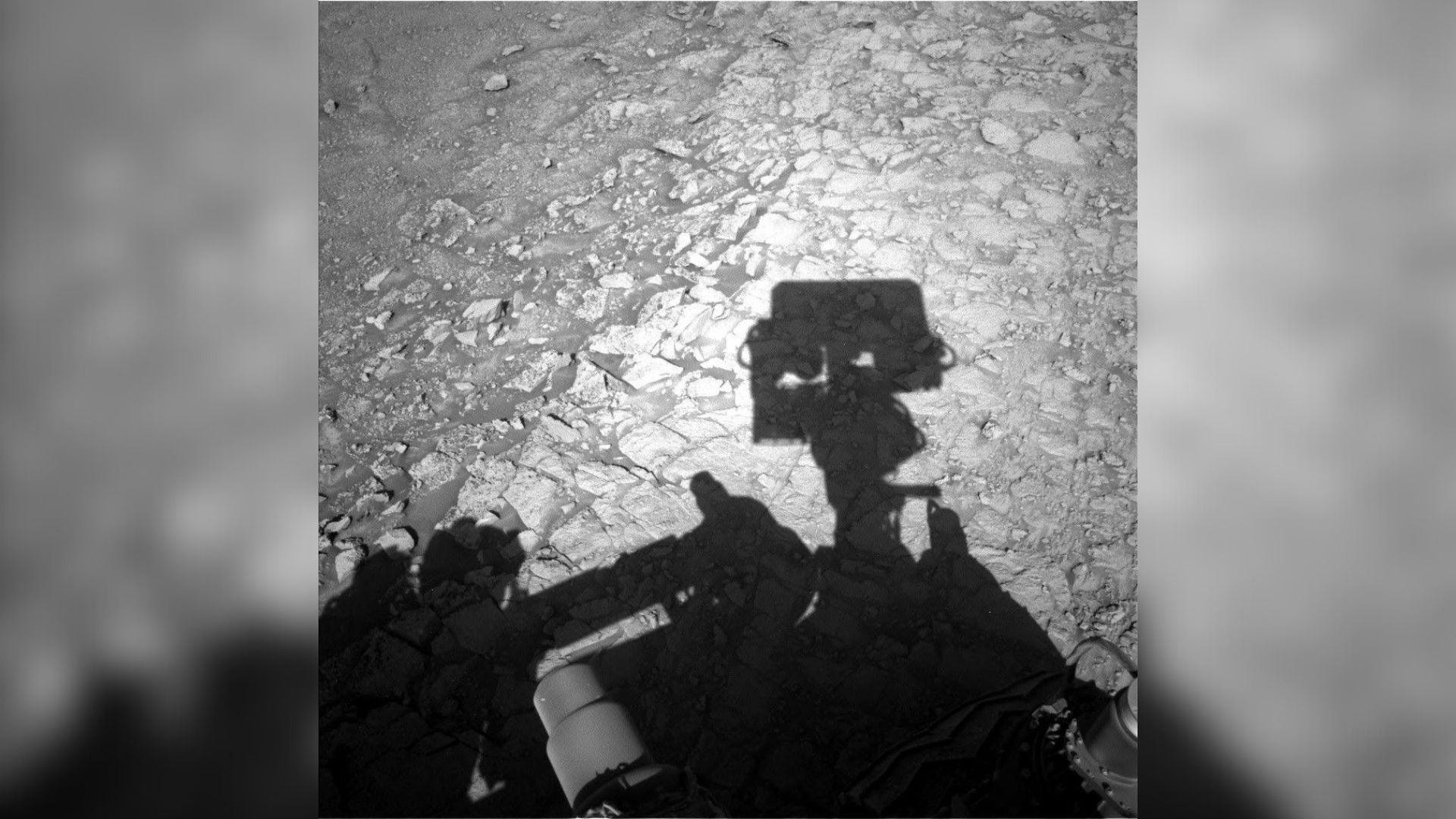

NASA’s Curiosity rover sends stunning new panorama from high on Mars’ Mount Sharp

By Samantha Mathewson published 2 days ago (Space.com)

The image was captured in November 2025, showing how lighting changes throughout the day on Mars.

NASA’s Curiosity rover captured this panoramic view from high on the slopes of Mount Sharp inside Gale Crater, combining images taken on two different Martian days in November 2025 to highlight changing light across ancient, water-shaped terrain. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)Share

NASA’s Curiosity rover has sent back a striking new “postcard” from high on the slopes of the Red Planet’s Mount Sharp, offering a dramatic look at the rugged Martian landscape the robot has been exploring for more than a decade.

The recent image is a composite panorama captured in November 2025 by Curiosity’s navigation cameras, spanning two Martian days, or sols, of the mission — Sols 4,722 and 4,723. Black-and-white images were taken at 4:15 p.m. local Mars time on Sol 4,722 and again at 8:20 a.m. on Sol 4,723.

Both were then combined into a single view that was tinted with cool blue and warm yellow hues to show how lighting conditions change over the course of a Martian day. “Adding color to these kinds of merged images helps different details stand out in the landscape,” NASA officials said in a statement releasing the new image.You may like

- Camera on NASA Mars probe snaps its 100,000th photo of the Red Planet

- NASA Perseverance rover sees megaripples on Mars | Space photo of the day for Jan. 7, 2026.

- NASA tests drones in Death Valley | Space photo of the day for Dec. 15, 2025

Click here for more Space.com videos…

In this new view, Curiosity was positioned on a ridge overlooking a region called the boxwork formation. This region contains intricate networks of mineral-rich ridges left behind when groundwater once flowed through cracks in the rock billions of years ago.

Over time, wind erosion stripped away softer material, leaving the hardened mineral veins exposed. Scientists are interested in these features because they preserve evidence of ancient water activity and changing environmental conditions on Mars, according to the statement.

Wheel tracks visible in the foreground show the rover’s slow, deliberate progress as it continues climbing Mount Sharp, a 3-mile-high (5-kilometer-high) mountain inside Gale Crater that has served as Curiosity’s primary science target since landing in 2012.

The rover has been carrying out hands-on science at this location. Using the drill at the end of its robotic arm, Curiosity recently collected a rock sample from the top of the ridge at a site dubbed “Nevado Sajama.” The panorama looks north across the boxwork formations and down the slopes of Mount Sharp toward the floor of Gale Crater. The crater’s rim is visible on the distant horizon, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) away, while wheel tracks mark a shallow hollow behind the rover where Curiosity previously drilled another sample at a site called “Valle de la Luna.”

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

Curiosity has been focused on studying boxwork terrain and other sedimentary layers that record Mars’ transition from a wetter, potentially habitable world to the cold, arid planet seen today. By analyzing rock chemistry, textures and mineral veins, the rover continues to piece together the story of how water once moved through Gale Crater — and whether those ancient environments could have supported microbial life.

In recent months, the mission team has been making greater use of new multitasking and autonomy capabilities, allowing the rover to conduct science observations while simultaneously communicating with orbiters overhead. These improvements make the rover more efficient, helping to maximize science output from Curiosity’s aging nuclear power source.

More than 13 years after its arrival on Mars, Curiosity is still delivering both breathtaking views and valuable science, proving that the Red Planet has many more stories left to tell.

Contributing Writer

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.

Trump Asks National Intelligence Point-Blank If God Real

Published: January 7, 2026 (TheOnion.com)

WASHINGTON—Cutting off a top security advisor mid-speech as he eagerly posed his question, President Donald Trump reportedly interrupted a briefing Tuesday to ask officials from the National Intelligence Council whether God was real. “So what do we know about Him? Are there any photos?” said a quizzical Trump, adding that he brought the matter up to multiple directors of national intelligence during his previous administration but never received a satisfying answer. “Let’s just cut to the chase here: big guy in heaven. Is He real or not? And if so, have we made contact? You know, there’s a very smart boy who died and says heaven is for real—does the CIA have any files on him? Who here knows? I want every document we have on God released immediately.” At press time, members of the U.S. Intelligence Community were reportedly reassuring Trump that God was real, He had lots of money, and they would immediately look into suing Him for $200 million.

How to See More Clearly and Love More Purely: Iris Murdoch on the Angst of Not Knowing Ourselves and Each Other

By Maria Popova (themarginalian.org.)

One of the hardest things to learn in life is that the heart is a clock too fast not to break. We lurch into loving, only to discover again and again that it takes a long time to know people, to understand people — and “understanding is love’s other name.” Even without intentional deception, people will surprise you, will shock you, will hurt you — not out of malice, but out of the incompleteness of their own self-knowledge, which continually leads them to surprise themselves. More often than not, when someone breaks a promise, it is because they believed themselves to be the kind of person who could keep it and found themselves to be a person who could not. If we live long enough and honestly enough, we will all find ourselves in that position eventually, for in the lifelong project of understanding ourselves, we are all reluctant visitors to the dusky and desolate haunts of our own nature, where shadows we do not want to meet dwell. But in any human association that has earned the right use the word love, we must be in relationship with both the light and the shadow in ourselves and each other. All authentic relationship is therefore a matter of clear sight — of seeing through the shining pane of the other’s self-concealment and removing the mirror of our own projections.

Art from An Almanac of Birds: 100 Divinations for Uncertain Days. (Available as a print and as stationery cards, benefitting The Audubon Society.)

Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) explores this central perplexity of human life with her characteristic intellectual agility and emotional virtuosity in one of the essays found in Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library) — one of my all-time favorite books, which also gave us Murdoch on what love really means, the myth of closure, and the key to great storytelling. She writes:

People are so very secretive. Sometimes it is said, “Those characters and that novel are purely fantastic — nobody in real life is like that.” But people in real life are very, very odd, as soon as one gets to know them at all well, and they conceal this fact because they are frightened of appearing eccentric or shocking… What are other people really like? What goes on inside their minds? What goes on inside their houses?

It is, of course, impossible to ever fully know what it is like to be someone else — this is the cost of consciousness, singular and secretive as it is; impossible, too, to fully convey to another what it is like to be you. The dream of perfectly clear vision is indeed just a dream. But we can always see a little more clearly in order to love a little more purely.

Iris Murdoch

Paradoxically, while our illusions about ourselves and others are the work of fantasy, seeing clearly is the work of the imagination — of the willingness to investigate imaginatively what lives behind the masks people wear, what hides in our own blind spots. Murdoch writes:

Imagination, as opposed to fantasy, is the ability to see the other thing, what one might call, to use those old-fashioned words, nature, reality, the world… Imagination is a kind of freedom, a renewed ability to perceive and express the truth.

In another essay from the book, Murdoch considers the existential jolt of discovering how poorly we know ourselves, for we are always divided between our will and our personality, the conscious and the unconscious. Whenever we face the abyss between the two, we are overcome with an uneasy feeling the existentialists called Angst. Defining it as the “fright which the conscious will feels when it apprehends the strength and direction of the personality which is not under its immediate control,” Murdoch locates Angst in any experience where we feel the discrepancy between our ideals and our personality. She writes:

Extreme Angst, in the popular modern form, is a disease or addiction of those who are passionately convinced that personality resides solely in the conscious omnipotent will.

In a sense, Angst — which often manifests as anxiety, to use a presently fashionable term — is the loss of faith in the omnipotence of the rational will, the discovery that much of our conduct is governed by unconscious tendrils of our personality impervious to our conscious ideals. This makes the project of change far more complex and durational than we would like it to be.

Art from An Almanac of Birds: 100 Divinations for Uncertain Days. (Available as a print and as stationery cards, benefitting the Audubon Society.)

Murdoch writes:

The place of choice is certainly a different one if we think in terms of a world which is compulsively present to the will, and the discernment and exploration of which is a slow business. Moral change and moral achievement are slow; we are not free in the sense of being able suddenly to alter ourselves since we cannot suddenly alter what we can see and ergo what we desire and are compelled by. In a way, explicit choice seems now less important: less decisive (since much of the “decision” lies elsewhere) and less obviously something to be “cultivated.” If I attend properly I will have no choices and this is the ultimate condition to be aimed at… Will continually influences belief, for better or worse, and is ideally able to influence it through a sustained attention to reality.

This is so because pure attention reveals the fundamental necessity of our lives, and where there is necessity there is no need for choice — there is only what Murdoch calls “obedience to reality,” which is always “an exercise of love.” Such attention — “patient, loving regard, directed upon a person, a thing, a situation” — shapes what we believe to be possible and, when coupled with the conscious will, shapes our lives. It is only through obedience to reality that we can ever see clearly enough — ourselves or another — to be in loving relationship, by discovering, in Murdoch’s lovely words, “the real which is the proper object of love.”

Couple this fragment of the altogether superb Existentialists and Mystics with Adam Phillips on the paradoxes of changing, then revisit Iris Murdoch on how attention unmasks the universe and how to see more clearly.

Sun Conjunct Venus And Mars – All Is Fair In Love And War

(Astrobutterfly.com)

Behind the scenes, something important is resetting.

Between January 7th–9th, 2026, we have a rare triple conjunction between the Sun, Venus, and Mars in mid-Capricorn.

First, on January 7th, the Sun conjuncts Venus at 16° Capricorn. This is the turning point in Venus’ synodic cycle, when Venus shifts from a morning star to an evening star.

The following day, Venus catches up to Mars and makes an exact conjunction at 18° Capricorn. On January 9th, the Sun conjuncts Mars at 19° Capricorn, initiating a brand-new 2-year Mars cycle.

The geometry of this configuration is spectacular. We won’t see anything in the sky, with Venus and Mars too close to the Sun and therefore ‘invisible’ – yet there is some serious Game of Thrones-type twist happening behind the scenes.

What might look like a celestial agreement – Sun, Venus, and Mars all aligned – is actually much more complex, with new beginnings and endings happening simultaneously.

Let’s unpack this.

We’ll start with Venus

When the Sun is conjunct Venus and Venus is direct (like it is now) we have a so-called ‘superior’ Venus conjunction.

This is the “Full Moon” – or better said, the “Full Venus” – phase of Venus’ 584-day cycle: a culmination or turning point where something about our values and relationships reaches a peak and then matures into a new phase.

Basically, Venus hits a climax point in her story. After wandering the early-morning sky, doing her own thing, Venus is now connecting with the Sun (our life purpose) and being brought into conscious alignment with it – “let’s drop the nonsense – this is what I actually want”.

This is less about outer events and more about Venus doing something decisive on the inside.

When Venus conjuncts the Sun, something ‘clicks’: and as a result of this ‘click’, we re-rank priorities, rewrite relationship contracts, and redefine what’s worth it – and what’s not.

What about Mars?

Mars cycles are about how we go after what we want. Mars cycles are very important because they describe what we actually do – in the real world.

When Mars is reborn with the Sun, our instinct resets, and we feel motivated to start again with a new set of goals.

A Sun – Mars conjunction marks the beginning of a brand-new hero or heroine’s journey – a time to start afresh with new intentions, and make new commitments.

Sun, Venus And Mars

What’s especially interesting is that right now the Venus and Mars cycles overlap, creating a triple Sun-Venus-Mars conjunction.

This triple conjunction is not accidental, but part of a pattern.

Venus-Mars conjunctions form a broader 32-year rhythm; each conjunction belongs to a “series” – and in the midpoint of each series, there is a Venus-Mars-Sun conjunction.

New series begin in a Venus-led way – she’s “calling the shots” – the whole cycle is basically rooted in these Venusian values and desires that have been stirred inside of us.

So the Sun-Venus-Mars conjunction is the midpoint checkpoint in the Venus-Mars story, where the relationship between desire (Venus) and actions (Mars) is re-coded through the Sun.

What might look like a celestial agreement – Sun, Venus, and Mars all aligned – is actually a high-stakes behind-the-scenes rewrite.

Venus is at a turning point in her cycle (values/desire reorient). Mars is at the start of his cycle (will and action reset). Venus and Mars meet (the lover and the warrior renegotiate the terms).

All of this unfolds under the Sun (identity and purpose become the arbiter).

The Sun is our identity and life purpose, so this checkpoint is a reality check – clarifying how our wants and desires need to be adjusted if they’ve become misaligned, unrealistic, or out of touch with our deeper purpose.

From this adjustment, Mars then takes the lead, translating revised values into action and taking the necessary steps to make these recalibrated goals and desires real.

The conjunction between Venus and Mars is incredibly important, because Venus is the feminine, yin principle, and Mars the masculine, yang principle.

When the 2 meet, creation becomes possible. Something that didn’t exist before takes shape through this ‘chemical’ reaction.

Sun Conjunct Venus Conjunct Mars In Capricorn

The Sun-Venus-Mars conjunction is in Capricorn. Capricorn is the part of the zodiac where the rubber meets the road: goals, systems, deep commitments, contracts, status, and long-term consequences.

When the Sun, Venus, and Mars meet in Capricorn, we become more driven and motivated to clarify our personal wants and desires and find ways to manifest them in the real world. This is when our sense of drive and achievement is at an all-time high.

At the same time, this is a conjunction, and we might not see results externally quite yet. Rest assured though that when Mars opposes the Sun next year, what’s being set in motion now will eventually manifest.

And this is part of an even larger pattern.

Back in February 2022, we had a Venus-Mars conjunction at 16° Capricorn.

While Venus and Mars conjoin roughly every 32 months, a new Venus-Mars conjunction series in a given zodiacal sign begins roughly every 32 years.

The 2022 Venus-Mars conjunction in Capricorn marked the start of a new Capricorn series, with the January 2026 Sun-Venus-Mars conjunction acting as a moment of illumination and alignment for what was seeded then.

Can you recall what was going on in your life back in 2022, when this new 32-year Capricorn Venus-Mars cycle started?

The current Venus-Mars-Sun conjunction is a continuation and activation of that theme.

The Psychology Of Venus And Mars

Venus and Mars are the ‘relationship’ planets, and quite literally so – from Earth’s perspective, they are our closest planetary neighbours. Venus is just before Earth, and Mars after.

First, Venus informs us (Earth) of what’s important – what we value, desire, and are drawn toward – and then we take action (Mars) based on this internal valuation.

When Venus and Mars are activated together, we’re operating simultaneously from desire (Venus: attraction, value, want) and will (Mars: drive, pursuit, action).

Venus+Mars is the “Veni. Vidi. Vici” part of the psyche that says: “I want this. I’m going after it. I will get it.”

It’s pre-rational and pre-moral. Venus and Mars describe what matters to us at a raw, instinctual, survival-instinct level – beyond what the Sun, the king of our solar system, consciously defines as purpose or meaning.

Venus and Mars are not about logic, but about what keeps us moving, what feels right, rather than what sounds right.

Is All Fair In Love And War?

“All is fair in love and war” is a well known expression with roots in classical thought and Roman rhetoric.

The phrase basically describes what people do, not necessarily what they should do in situations when the stakes are high, and outcomes matter more than procedures or etiquette.

Used uncritically, “all is fair in love and war” can become a justification for harm: betrayal, manipulation, or cruelty disguised as necessity.

“All as fair in love and war” doesn’t carry a negative connotation by default. It simply describes moments when the parts of our psyche that defy logic – Venus and Mars – take center stage.

And whether this leads to a constructive or destructive outcome depends entirely on how conscious, healthy, and honest our personal relationship with Venus and Mars is.

This is similar to alcohol. We could ‘blame’ our passions or anger to justify our actions – but they simply reveal our inner state, what we really want, and what we really want to do.

We can say “alcohol made me do it,” to justify bad behavior or a situation that wouldn’t have happened otherwise, when in reality, alcohol doesn’t create anything new – it simply removes inhibitions and filters.

Some people become funnier or more generous after a few glasses; others become harsher or more aggressive.

It’s more that alcohol loosens our Mercury (perception) and Jupiter (moral compass) functions, and what is left is Venus and Mars – our desires and drives.

Again, that’s not to say that there is something inherently wrong with our Venus and Mars.

As Shakespeare puts it, “Brutus, the fault is not in the stars, but in ourselves.”

Sometimes, engaging our Venus and Mars is exactly what we need.

In a ‘what do others think of me?’ or over-analyzing, mentality-driven reality, allowing Venus and Mars to take center stage is the best thing to do. Sometimes, we need that fire under our belly.

Whatever makes us angry, driven, aroused, or compelled does so for a reason. There’s something fundamental about it that wants to be lived and materialized, and it’s through Venus and Mars – our wants and desires – that we access and activate that latent potential.

Psychologically, love (Venus) and war (Mars) activate our primal systems: threat, desire, fear of loss, fight-or-flight. Under these conditions, our ego loosens its usual restraints – and that’s not always a bad thing!

Sun Conjunct Venus And Mars – All Is Fair In Love And War

Sometimes heart and instincts know better than the mind. When life feels dull, alienating, or not truly ours, reconnecting with our primal drives is precisely the reset we need.

Sometimes, indeed, all is fair in love and war – or better said, there is truth in extreme circumstances or intense feelings or drives that are otherwise muted or blocked by our inner critic.

The “all is fair” phrase doesn’t really mean everything is fair – it means that when impulse is allowed to lead, everything becomes possible.

It’s describing what happens when Venus-Mars takes the wheel and Mercury and Jupiter step back, when the psyche prioritizes doing over rationalizing, and immediacy over legitimacy.

All this feeling- and instinct-based momentum could potentially turn reckless. And this is where Capricorn energy comes in – asking not just what feels necessary in the moment, but what holds up over time.

Will we still be proud of what “Venus and Mars made us do” 10 or 20 years from now? Is it something our children and grandchildren would look at with admiration, or would it become just another shameful, buried secret passed down through the lineage?

For all of us, the Sun-Venus-Mars conjunction asks us to align our life purpose (Sun) with our heart and our actions. This is a moment to clarify what truly matters to us – despite shoulds, narratives, conditioning, or inherited rules and expectations.

We might think with our mind, but we “know” with our hearts. There is truth, realness, and aliveness in our desires when we allow ourselves to listen to them:

- What do I want? (Venus)

- What am I willing to do to get it? (Mars)

- How is this aligning with my life’s purpose? Am I showing up for it, yes or not? (Sun)

In other words: what matters enough to move me? What am I willing to risk? When desire, will, and purpose align, something real can be built. Right now, everything else is noise.

UCSF, Stanford to study links between AI use, mental health

- By Troy Wolverton | Examiner staff writer

- Jan 5, 2026 (SFExaminer.com)

Although there have been numerous media reports and a collection of lawsuits over the last two years attempting to link the use of artificial-intelligence chatbots such as ChatGPT to mental-health crises, there has been little scientific examination of their relationship to date.

Researchers at UCSF and Stanford University are planning to study that interaction more systematically soon.

In the near future, UCSF psychiatry and behavioral-sciences patients will likely be asked about their AI chatbot use as part of the regular office visit intake process. And in collaboration with colleagues at Stanford, researchers in the department are planning to ask patients to voluntarily share their chatbot logs to see if the researchers can make any connections between patients’ chatbot conversations and their diagnosed conditions or changes in their mental health.

“We are really interested in looking at the relationship between mental illness and how people use chatbots, and the interplay between those things,” said Dr. Karthik Sarma, a computational-health scientist at UCSF who works in the psychiatry department and is heading up the research effort there.

For the research project, Sarma is working with Stanford’s mental health-focused Brainstorm Lab and the Stanford Intelligent Systems Laboratory, which studies automated decision-making applications. The project was inspired by OpenAI’s disclosure in October that it had detected signs of psychosis and suicide planning or intentions in small fractions of its active weekly users, he said.

Right now, mental-health clinicians don’t generally ask patients about their chatbot use as a matter of routine at UCSF or elsewhere, Sarma said. But after June, when UCSF physicians diagnosed the first of what has become a handful of cases of AI-related delusions there, they started thinking about whether they should begin routinely screening for chatbot use, according to Dr. Joseph Pierre, Sarma’s colleague in the department.

UCSF physicians began making the connection between delusions and the use of chatbots by asking patients about the latter, said Pierre, the chief of the inpatient unit at UCSF’s Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital. They were spurred to do so by media reports about people whose extensive AI use appeared to be inducing psychoses, he said.

The discovery of those cases prompted Pierre and his colleagues to want to study the issue more systematically, he said. Currently, discussion of chatbot use with patients is kind of ad-hoc, he said — it’s not something that he asks of every patient; instead, it typically comes up if a patient mentions it.

That makes it impossible to know how prevalent chatbot use is among patients or often it’s leading to delusions or other problems, he said.

There’s “probably a bunch of people who we never bother asking and don’t detect,” Pierre said.

Sarma’s screening effort would seek to change that. He and his colleagues are still working out the details, but the plan is to pattern the effort after the screenings they already perform when patients walk in the door.

Pretty much every psychiatric patient fills out a survey asking how they are feeling, whether they’re experiencing depression or have thought about harming themselves, Sarma said. Physicians also routinely ask patients about their housing situations, what they’re eating and whether they’ve been exercising.

As Sarma envisions it, they would be asking patients about chatbot use as well with similar regularity. The idea would be to find out if patients are using chatbots, which ones they’re using and how frequently and for how long they are using the systems, he said. Clinicians also would like to get a sense of the purposes for which patients are using chatbots, such as whether patients are turning to the systems for assistance with their mental or emotional health.

Such data could be linked to patients’ ages to see if any trends emerge, he said. And patients would be asked about their chatbot use with every visit to track changes over time, he said.

“It’s seeming like using AI chatbots may become a part of everyday life that we should be talking to everybody about, or at least finding out from everybody about what’s going on,” he said.

At least initially, the effort would likely focus on people who visit the department on an outpatient basis, Sarma said. That’s because they represent the vast majority of UCSF’s psychiatric and behavioral patients, he said. Additionally, patients who are checked into the hospital are often suffering from symptoms that are so severe that it isn’t feasible to screen them, he said.

Sarma said he didn’t know when UCSF will begin regularly asking patients about their chatbot use, but said he’s hopeful it will start soon. UCSF will likely launch the effort by putting together a prototype survey, testing it and then revising it over time, he said. Eventually, the goal would be to do near-universal screening, he said.

“It may be some time before we get to the point where everyone is screened,” he said. “But … it’s easy to imagine, if it turns out to be useful, that someday we might screen everybody for how they’re using AI.”

While OpenAI and other AI chatbot developers have access to their users’ chat conversations, they don’t have access to patients’ clinical histories, so it can’t definitively tie their interactions to diagnosed mental-health problems, Sarma said. By contrast, UCSF physicians know their patients’ clinical histories, but don’t know what they’re discussing with their chatbots.

Sarma and his colleagues plan to ask patients for access to their chatbot conversations. They want to look at how those conversations developed over time and their patients’ symptoms to see if there’s a relationship between the two, he said.

The researchers are going into the potential study assuming from previous research that they’ll find widespread use of chatbots, Sarma said. But they aren’t going into it with a particular hypothesis about the nature of the relationship between that use and mental health, he said.

For some people at some times, chatbot use could be beneficial to their mental health, he said. At other times or with other people, it could be associated with a worsening of their symptoms. It could also be that different types of people are affected differently by similar chatbot use, he said.

“We’re going in with our eyes open and our hearts open to what we might find,” Sarma said.

Duncan Eddy said that he and his colleagues at SISL have been studying how particular prompts can cause the large-language models that underlie ChatGPT and other chatbots to fail. They’ve looked at how small or subtle changes to prompts can induce toxic or harmful responses from such models.

They’ve also begun to study how the models react to inputs that indicate mental-health conditions. An outgrowth of that research was the work Eddy’s colleagues at Stanford Brainstorm performed with Common Sense Media that found that chatbots struggle to detect signs of mental-health crises in longer interactions. In response to that finding, Common Sense advised parents not to let their kids use chatbots for companionship or mental-health conversations.

Eddy said that thus far, his research has focused on how the chatbots respond to synthetic prompts, ones generated by the researchers themselves or an automated system. Using input from mental-health experts, he and his Stanford colleagues have been working on a way to automatically evaluate the chatbots’ responses to related prompts.

Eddy said he met Brainstorm founder Nina Vasan through Stanford’s Center for AI Safety, where Vasan is a faculty member and Eddy is a postdoctoral scholar. Vasan connected Eddy with Sarma — who is her partner — and his team at UCSF when Sarma came to give a talk at Stanford.

The collaboration with UCSF represents an opportunity to take the system they’re developing and use it to analyze and evaluate the conversations the chatbots are having with actual mental-health patients, he said. They’ll be looking for risk factors and early warning signs in the prompts and responses that can be linked to changes in patients’ mental health. They’ll also potentially be looking at whether people who are showing signs of mania are more likely to be using one chatbot or another, he said.

Essentially, though, they’ll be trying to figure out where the conversations go off track in ways that have been linked to delusions.

“I think it’s going to be one of the first studies, hopefully, of really trying to understand these types of incidents from a research perspective,” Eddy said.

“There seems to be something there, but no one has actually done … the rigorous work to see what the causes of the relationship are, and then what we can actually do about it,” he said.

The Stanford researchers already have funding for their AI-safety efforts via a grant from the family foundation of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife, Wendy, Eddy said. They’ve applied for a grant from OpenAI to fund the study involving clinical data, but haven’t yet heard whether they will receive it, he said.

Like Sarma, Eddy said he isn’t going into the study with any particular hypothesis about what they’ll find. At this point, he and his team are looking for “reliable signals” of problems.

“I’m trying to keep an open mind right now and let the data speak for itself right now,” he said.

That said, he said he suspects that such a signal that people are in distress might be simply the frequency with which they are interacting with a chatbot or the duration of their conversations. It could be that a reliable indicator that someone is having a harmful conversation with a chatbot is whether they are sending thousands of prompts or interacting with it for hours on end, he said.

“It might even be the detection actually is independent of the actual quality or input of the responses,” he said.

If you have a tip about tech, startups or the venture industry, contact Troy Wolverton at twolverton@sfexaminer.com or via text or Signal at 415.515.5594.

Vermeer: Woman Holding a Balance

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS isn’t an alien spacecraft, astronomers confirm. ‘In the end, there were no surprises.’

By Robert Lea published yesterday (Space.com)

“We all would have been thrilled to find technosignatures coming from 3I/ATLAS, but they’re just not there.”

(Image credit: Robert Lea (created with Canva))Share

Space fans hoping that the intruder from beyond the solar system known as Comet 3I/ATLAS is actually an alien spacecraft may be disappointed by new research that could close the book on this speculation once and for all.

Astronomers used the Green Bank Telescope, employed in the Breakthrough Listen extraterrestrial signal-hunting astronomy project, to search 3I/ATLAS for measurable signs of technology from extraterrestrial civilizations, or “technosignatures.”

Though this hunt came up empty, the fact that 3I/ATLAS is only the third known object found in the solar system after entering from interstellar space (the others being 1I/’Oumuamua, seen in 2017, and 2I/Borisov, detected in 2019) means that it is still an object of great fascination, albeit a natural one.You may like

- 4 key things NASA just revealed about the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

- How did interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS capture our imagination in 2025?

- NASA reveals new images of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS from across the solar system: ‘It looks and behaves like a comet’

Click here for more Space.com videos…

“We all would have been thrilled to find technosignatures coming from 3I/ATLAS, but they’re just not there,” lead researcher Benjamin Jacobson-Bell from the University of California, Berkeley, told Space.com. “Finding no signals was the result we expected, due to the significant evidence for 3I/ATLAS being a comet with only natural features.

“The evidence was against 3I/ATLAS being one such probe, but we would have been remiss not to check.”

Jacobson-Bell explained that scientists have even discussed conducting this exact kind of exploration using probes of our own. An example of this is the Breakthrough Starshot initiative, a concept that proposes to launch thousands of extremely lightweight probes toward Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to our sun.

“There are compelling reasons to think a spacefaring species would send probes to other star systems as a way to learn more about their stellar neighborhood,” Jacobson-Bell added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

Tuning in to radio 3I/ATLAS

The team behind this research theorized that if we find them, the brightest extraterrestrial technosignatures are likely to be narrowband radio signals, because these take comparatively little energy to produce and travel well over long distances.

“Breakthrough Listen searches for life beyond Earth in a variety of ways. The Green Bank Telescope is a radio dish 100 meters wide, situated in a zone federally regulated to be free of most radio interference,” Jacobson-Bell said. “Its sensitivity enables us to verify the absence of transmitters down to 0.1 watts, the strongest evidence against technology of any 3I/ATLAS observation to date.”

For comparison, modern cell phones typically emit radio waves at roughly the 1-watt level.You may like

- 4 key things NASA just revealed about the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

- How did interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS capture our imagination in 2025?

- NASA reveals new images of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS from across the solar system: ‘It looks and behaves like a comet’

“This is to say that if there were any transmitters on 3I/ATLAS up to ten times weaker than a cell phone, we would have found them,” Jacobson-Bell continued.

“Humans produce a lot of narrowband radio signals, including for communication with our own spacecraft,” Jacobson-Bell said. “However, by modeling our search strategy on human technological output, we end up detecting a lot of human-made signals! Therefore, we run any detections through filters to distinguish probable human-made interference from possible extraterrestrial signals.”

The Green Bank Telescope covers a very broad range of radio frequencies, meaning the team is unlikely to have missed any signals purely because they were looking in the wrong part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

“We did find nine ‘events,’ which is our term for signals that pass certain filters in our search strategy, but on closer inspection, we could readily attribute all nine of them to known radio transmitters here on Earth,” Jacobson-Bell said. It’s very common to find, then discard, false alarms like this.

“Past work has shown that 3I/ATLAS looks like a comet and behaves like a comet, and our observations show that, like a comet, 3I/ATLAS is not a source of technological signals. In the end, there were no surprises.”

As Jacobson-Bell pointed out, this may be perhaps slightly disappointing, but it doesn’t mean that 3I/ATLAS isn’t still hugely scientifically significant.

“There is considerable excitement around 3I/ATLAS because it’s only the third-ever discovery of an interstellar object within our solar system,” he continued. “Sending spacecraft to other star systems could be very informative, so it’s tempting to imagine that some interstellar objects might be intentional probes.”

Jacobson-Bell believes that discoveries of interstellar objects are likely to become much more common as the recently completed Vera C. Rubin Observatory begins its 10-year-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

“Whereas each individual interstellar object is currently an anomaly, future surveys will amass such a population of interstellar objects that we’ll start to be able to tell which are typical and which are actually anomalous,” he said. “Some of these objects will merit follow-up observations — could their anomalies be due to technology?”

This new research and its findings regarding 3I/ATLAS thus pave a path toward answering that question.

“We hope our search helps dispel the idea that this object is artificial, but likewise we hope that public interest in interstellar objects remains strong — they’re very interesting whether they’re spacecraft or comets, and it’s entirely possible that one day, one of them will indeed be transmitting technological signals,” Jacobson-Bell concluded. “If we don’t look, we’ll never know.”

The team’s research is available as a pre-peer-reviewed paper on the repository site arXiv.

Senior Writer

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

Lost Jan. 6 Rioter Still Searching Capitol Building For Mike Pence

Published: January 6, 2026 (TheOnion.com)

WASHINGTON—As he wandered aimlessly through the halls of the U.S. Capitol building, lost Jan. 6 rioter Alex Morris told reporters Tuesday that he was still searching for former Vice President Mike Pence. “Oh my God, how am I back in Statuary Hall again? Where the hell is Pence?” said Morris, tucking a noose under his arm while opening Google Maps and reorienting himself in the direction of the National Mall. “At this point, I can barely remember why I wanted to hang the guy in the first place. It feels like I’ve circled the Senate Chamber a million times. Does anyone know where Ashli Babbitt is? She knows her way around here.” At press time, Morris reportedly attempted to jog his memory by taking a shit in the office of Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA).