- By Margaret Hetherwick | Examiner staff writer |

- Mar 28, 2023 Updated Apr 4, 2023 (SFExaminer.com)

Molecular biologists at UCSF have made a breakthrough in understanding the human sense of smell — a notoriously ephemeral process that has evaded precise description until now.

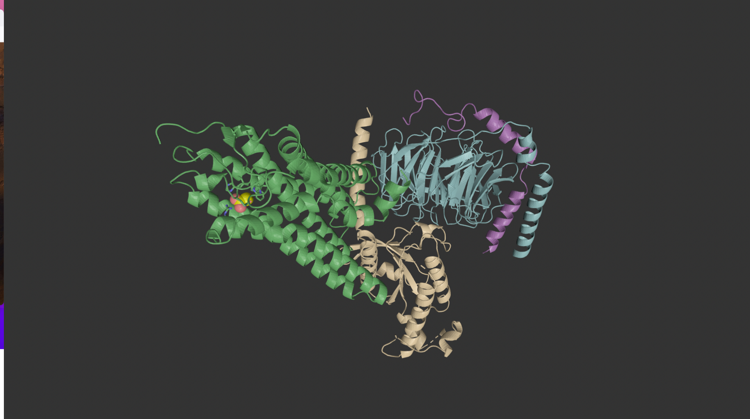

This month, for the first time, researchers were able to capture how a human odor receptor detects a scent molecule. Click here to view the interactive 3D model.

Aashish Manglik, an associate professor of pharmaceutical chemistry, explained that this is just the first piece of a very large map. The human sense of smell is the least understood of the physical senses and one of the most complex.

“This has been a huge goal in the field for some time,” he said. “But we haven’t been able to make this map because, without a picture, we don’t know how odor molecules react with their corresponding odor receptors.”

The team started out with a distinct, instantly recognizable scent — Swiss cheese — but eventually, as the scent map grows, a chemist could design a molecule and predict what it would smell like, said Manglik.

Scents, like flavors, are usually a harmony of molecules. Humans can detect hundreds of thousands of scents, and we use over 400 unique olfactory receptors to pick apart a smell when we detect one. The information we pick up from a scent can indicate whether or not something is edible or dangerous.

Propionate — the molecule that gives Swiss cheese its rich, pungent scent and taste — is very harsh by itself. First, Manglik’s team had to isolate the human protein that detects it — a nigh impossible task — then watch it closely to see the magic.

They found that the odor detectors only interacted with the propionate molecules in a very specific way — like a white blood cell catching germs.

“This receptor is laser-focused on trying to sense propionate and may have evolved to help detect when food has gone bad,” said Manglik. Detector proteins for pleasing smells like menthol or caraway might interact more loosely with the odors, he speculated, because they indicate medicinal or edible uses.

The effects of smells are not just knee-jerk “don’t eat that” repulsions or a pleasant reaction. The human microbiome is becoming more relevant in modern medicine, and the way smell interacts with it could mean big strides.

A positive association with a smell can be linked to serotonin release in the gut, for example. A negative smell may kick-start a form of prostate cancer.

With a comprehensive scent map, Manglik envisions new avenues in medicine, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food.

“We’ve dreamed of tackling this problem for years,” he said. “We now have our first toehold, the first glimpse of how the molecules of smell bind to our odorant receptors. For us, this is just the beginning.”

Molly Hetherwick

Margaret is a general assignment reporter for The Examiner and a graduate of UC Santa Cruz.