is a theatre, film and television actor living in New York City. Some of his notable performances feature in the HBO TV series John Adams (2008), the Showtime TV series Billions (2016-), and the films American Splendor (2003) and Sideways (2004).

is professor of philosophy at Columbia College Chicago and a member of the Public Theologies of Technology and Presence programme at the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley, California. He is the author of many books, including The Evolution of Imagination (2017), Why We Need Religion (2018) and his latest, The Emotional Mind: Affective Roots of Culture and Cognition (2019), co-authored with Rami Gabriel. Listen here

Brought to you by Curio, an Aeon partner

23 March 2021 (aeon.co)

Edited by Brigid HainsSYNDICATE THIS ESSAYTweet1,3238 Comments

Aeon for Friends

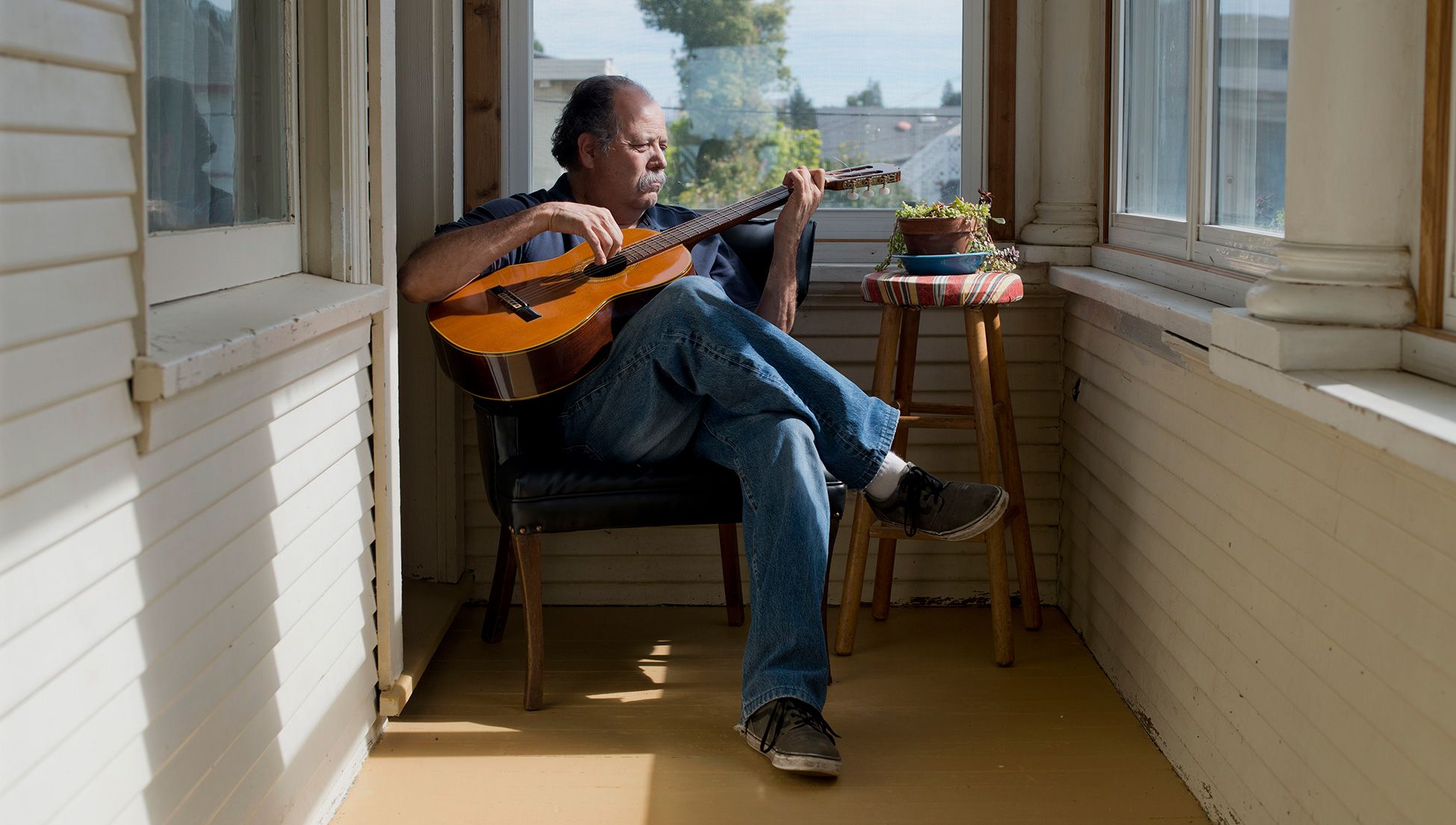

When I performed in the play The Iceman Cometh (1946) by Eugene O’Neill, I played a character who stands up near the end and pours his heart out on stage. My character was almost like a messenger in a Greek tragedy but, instead of describing some nightmarish battle, he had to recount the horror of his own failures and the regrets of his life. It was an intense, emotionally draining experience, and I had to do it night after night. Each night I wondered if I could do it again, but somehow the energy of the room, the other actors and the story itself helped me to dial in some deep emotional frequency from my own history. It feels like you’re a shaman because you kind of lose yourself and channel something. And that activates deep emotions in the audience, too. So there’s a weird connection – I’m losing myself, and the audience is losing themselves. Then we come down together, having shared something powerful.

– Paul Giamatti

Like other artists, the actor is a kind of shaman. If the audience is lucky, we go with this emotional magician to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional. How do actor and audience achieve this shared mysterious transportation? This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before us. Now they guide us like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of us.

Aristotle called this imaginative power phantasia. We might mistakenly think that phantasia is just for artists and entertainers, a rare and special talent, but it’s actually a cognitive faculty that functions in all human beings. The actor might guide us, but it’s our own imagination that enables us to immerse fully into the story. If we activate our power of phantasia, we voluntarily summon up the real emotions we see on stage: fear, anxiety, rage, love and more. In waking life, we see this voluntary phantasia at work but, for many of us, the richest experience of phantasia comes in sleep, when the involuntary imagination awakes in the form of dreams.

In The Descent of Man (1871), Charles Darwin writes:

The Imagination is one of the highest prerogatives of man. By this faculty he unites, independently of the will, former images and ideas, and thus creates brilliant and novel results … Dreaming gives us the best notion of this power; as Jean Paul [Richter] … says, ‘The dream is an involuntary art of poetry.’

The dreaming brain isn’t aware that the monster chasing us is unreal. During REM sleep, your body is turned off by the temporary paralysis of sleep atonia, but your limbic brain is running hot. In waking life, the limbic system is responsible for many of the basic mammalian survival aspects of our existence: emotions, attention and focus, and is deeply involved in the fight-or-flight response to danger. The dreaming brain isn’t just faking a battle but actually fighting one in our neuroendocrine axis. That’s why we sometimes wake up sweating with our heart racing. The involuntary imagination of dreaming creates an episode of emotional reality – not sham emotions. The same is true in the theatre, the movie, the novel. We’re really stirred by the St Crispin’s Day speech in William Shakespeare’s Henry V, really terrified by Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Pit and the Pendulum (1842), and really haunted by Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979).

The intensity of these emotions is not just felt by the audience. For an actor, embodying a scene with another actor – who reveals, say, a deep vulnerability from losing a child – can mean that a scripted fiction enacted by two strangers on a stage actually bonds the actors themselves in real intimacy long after the play or film is over. Like in a dream, the limbic mind experiences art as real. An actor or writer embodies the deepest traumas and joys of life so the audience can experience them vicariously. Acting (and other collective artistic work) can be a kind of mainlining of intimacy, and the audience partakes of this intimacy too.

There’s a lot of subtle embodied communication going on. There’s an intense awareness between the actors themselves, and between the audience and actors – especially in theatre. The most obvious feedback happens in comedies of course, because you can hear the laughs or the lack of them. But much more subtle stuff is happening too. Once, when I was playing Hamlet, there was an early scene with the Player King. His prop beard was slowly falling off his face – unbeknown to him – just as I was saying a line about beards. And there was this amazing energy in the whole place from the collective recognition that we were all playing in a play, but also a play that knows it’s a play. And sometimes when something goes wrong on stage – like a mistake, or a prop thing – it actually brings in a fresh energy by breaking the normal patterns, and everyone becomes more present in the room.

At other times, the emotional awareness is more intimate. Once I was playing the husband opposite the actor Kathryn Hahn in a scene where another character is inadvertently saying something insulting to her, and she doesn’t know what to say in response, and I’m trying to sort of cover it over, and then we just share this quiet moment together as we listen to the other character continue talking. They shot the scene many times, but then after one particular take we both looked at each other and said: ‘Wow, I really felt that one.’ And I think the authenticity of these kinds of connections can shine through to observers. For example, I think that was the take the director eventually used as well.

To prepare a role, the actor must function as an empathy sponge: they work to ingest and ingurgitate all the social nuances of power, vulnerability, hope and despair. This is a sensory osmosis – the actor must cultivate this like a sixth-sense organ. It happens ‘in the dark’ of the mind so to speak, beneath the radar of conscious thinking.

Nor does this rely on direct observations of human behaviour alone. According to the extended mind theory, humans offload much of who they are into the environment. The philosophers David Chalmers and Andy Clark argue that our minds don’t reside exclusively in our brains or bodies, but extend out into the physical environment (in diaries, maps, calculators and now smartphones, etc). Consequently, you can learn a great deal about someone by spending time in their home – not deducing facts like Sherlock Holmes, but absorbing subtle understandings of character, taste, temperament and life history. When an actor prepares to play a historical figure, he might find deep insights in the extended mind – the written record, the physical environs, the clothing and so on. A small detail can turn the key and open up a real ‘visitation’ from the past.

When I played President John Adams in the 2008 miniseries for HBO, I studied many historical records, but the key that helped me find his character was an amazing compilation of his health complaints. Someone had culled all his letters for any references to his health, and produced this giant record of elaborate and hypochondriacal health complaints. The man was a wreck with digestive problems, toothaches, headaches, bowel troubles and more. After manic periods of high energy, he would ‘take to his bed’ for a couple of weeks. In reading all this, I began to see how to play the everyday John Adams.

This capacity to get inside the emotional landscape of another person draws on a deep, evolutionary cognitive ability, a way of absorbing or reading what the psychologist James J Gibson called ‘affordances’. Gibson’s affordances can be understood as all the things that surround an organism in their environment, with potential to be understood, grasped and exploited. An affordance is relational: it depends on the ecological relationship between the animal and its lifeworld, rather than having an objective value. A freshly baked baguette is to a baker a proud symbol of her art; to the hungry child, it’s a meal; to the assistant at the boulangerie, an object to be arranged in the window. An affordance has meaning depending where you stand, and much of our grasp of affordances runs beneath conscious analysis. For social mammals, including humans, many of the affordances in our environment are social in nature, and thus we spend a huge amount of perceptual energy in processing signals of behaviour, demeanour and emotion from our fellows, much of which never surfaces to our conscious mind.

For Plato, the imagination produces only illusion. For Aristotle, it’s a necessary ingredient to knowledge

A chimpanzee, for example, sees the posture of the new guy as dominant – the dominance and subordinance exist in the real-time relationship between the two animals’ bodies and behaviours. The chimp doesn’t need to reason about the relationship, because the perception itself contains a great deal of information and prediction about status, disposition, character and possible behaviours. Stage actors ‘read the room’ in a similar way to our primate cousins reading their social world of dominance. A lifetime of subconsciously reading rooms (reading people) gives artists a rich palette of insights, feelings and behaviours. Unlike other animals, humans use phantasia to expand these affordances and create alternative behaviours – alternative realities – in the real-time present, as well as in the future. We take social affordances from our existing lifeworlds and spin new worlds out of them. That is the power of phantasia, but also, as we will see, its danger.

Some people think that the imagination is just a frivolous fantasy-making ability. For Plato, the imagination produces only illusion, which distracts from reality, itself apprehended by reason. The artist is concerned with producing images, which are merely shadows, reflecting, like a mirror, the surface of things, while Truth lies beyond the sensory world. In the Republic, Plato places imagery and art low on the ladder of knowledge and metaphysics, although ironically he tells us this in an imaginary allegory of the cave story.

By contrast, Aristotle saw imagination as a necessary ingredient to knowledge. Memory is a repository of images and events, but imagination (phantasia) calls up, unites and combines those memories into tools for judgment and decision-making. Imagination constructs alternative scenarios from the raw data of empirical senses, and then our rational faculties can evaluate them and use them to make moral choices, or predict social behaviours, or even build better scientific theories. For Aristotle, phantasia (which comes from the Greek word for ‘light’), is as important to knowledge as light is to seeing. Although Aristotle was careful to distinguish phantasia from the ordinary five senses, because it can occur without any stimulus from outside, we could understand phantasia as a kind of sixth sense, shared by humans and many animals, a way to know the world, to which humans return in dreams. Here, Aristotle is thinking of imagination as something like the involuntary process; the associational mashups of dreams, the subconscious tracking of affordances, the conditioned memories we use to evaluate and make sense of our experience. When we bring this process under executive control – that is, when we harness it to our waking, speculative and creative mind – we transform the involuntary imagination to voluntary, and this ‘phantasia 2.0’ is unique to humans. Perhaps a chimpanzee might dream of a hippo it once saw, but only a Walt Disney can bring the hippo to mind whenever he wants, dress it in a tutu in his mind’s eye, draw it, animate it dancing, and release it as a film called Fantasia (1940).

Contemporary science of the mind sides with Aristotle, not Plato. Phantasia is adaptive and helps us know others and ourselves better. Art is not just great for therapeutic emotional management and catharsis, but also produces knowledge, generating new ways of understanding and manipulating the world. Contemporary neurocognitive theory argues that the mind is a ‘prediction processor’. It builds mental models of the world, and tests predictions, always updating the model to reduce future errors. These cognitive processes are not possible without the imaginative faculty. The imagination helps us create possible futures (new architecture, medical breakthroughs, new political possibilities) but also helps us model other minds.

When art is good – when the acting and the script are on point, or a character in a novel is nuanced – the audience actually learns more about human behaviour than real-life observation provides. This is because the interior of the character is articulated in art, whereas it remains submerged in real social interaction.

We are, then, running a constant ‘simulator’ in our own minds, whether we’re consciously aware of it or not. Because of this involuntary sixth sense, we seem to know things without having figured them out. The dark processing (reading affordances, absorbing impressions from the extended minds around us, involuntarily combining narratives in headspace, and just simulating things) serves up ‘reality’ to us without revealing its hand in the construction. The mind is always incubating an alternative or supplemental reality. Our experience is always imagination-laden. Yet the vivid, and often unconscious, nature of this cognitive process isn’t always enriching. If imagination is an involuntary creative act of cognition before downstream rationality uses it, it can also be dangerous.

Without properly understanding imagination’s role in cognition, our views can present themselves to us as straightforward, accurate assessments of the world. People who disagree with us seem just ‘irrational’ (bad at weighing evidence and logic) or crazy. But once we take account of the imaginative layer of mind (the filtering and modelling we do between the raw data and the reasoned conclusions or beliefs), we see that the world itself really is different for the atheist as opposed to the Christian; the Republican as opposed to the Democrat; the rationalist versus the QAnon devotee.

The legal scholars Cass R Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule argue that conspiracy theories arise when people suffer from a ‘crippled’ knowledge base because they have ‘limited’ informational sources. If you watch only one news network, or get your ‘facts’ from a crank website or radio show with no peer review, then you’re going to be highly susceptible to conspiracy and this will likely be exacerbated if you received limited school instruction in logic and critical thinking in your formal education. Thus, the answer to conspiracy theories is more education and more rational weighing of information sources.

Conspiracy theories aren’t, however, just the result of alternative ‘information sources’ or limited information – we’re all awash in information. Rather, a potent conspiracy is a narrative arc in which the believer is a heroic character. Phantasia is a potent ingredient here. The persuasiveness of imagination consists in its embodied quality – the conspiratorial mind feels and sees itself as a protagonist in a drama. A dramatic story such as the QAnon theory is reinforced by a charismatic leader (politician/actor/clergy/celebrity), creating a phantasia layer that feels real, just as the dream feels real to the limbic system and the movie feels real to the audience member.

No wonder then that conspiracy theorists like to dress up. The conspiracy-minded Trump supporters who smashed into the Capitol Building in Washington, DC in January 2021 included half-naked ‘Ur-Americans’ with painted faces and buffalo headdresses, carrying signs that said ‘Q Sent Me’. A charismatic leader is like the shaman/actor on stage. They have ‘gone before’ into the embodied belief, they evoke the emotions, they involve the watcher/audience so intensely that everybody gets deeply invested. The insurrectionists in their dress-up costumes at the Capitol are less like actors and more like fully immersed audience members. The insurrection was a kind of malevolent cosplay convention in which superfans who had intensely internalised the narratives themselves took over the stage, only the ‘convention’ in this case was at the Capitol. Obviously, this makes them no less dangerous, because their guns are not props, and mob violence is wildly contagious.

Can we turn that awesome power of imagination toward humanising ourselves and others?

Our phantasia is not just ‘in our heads’ but actually extended and distributed into our environment. Just as the actor changes into costume and transforms into a new persona, so too the jingoist drapes himself in flags and paraphernalia becoming a new persona – one that feels righteous and empowered, in this case, to do violence. There is ‘magic’ in the accoutrement. Anthropologists and social psychologists have long recognised the unique dynamics in ritual adornment and behaviour. Ritualised collective imaginings help to produce what the French sociologist Émile Durkheim in 1912 called ‘collective effervescence’ – a feeling state or force that excites individuals and unifies them into a group. It’s a similar phenomenon in political crowds, religious ceremonies, music concerts and theatre experiences.

In our current climate of partisan paranoia, we’ve all ramped up imaginative demonisation of the other. This leaves us vulnerable to dark imaginings. The Chinese American philosophical geographer Yi-Fu Tuan states it plainly in his book Landscapes of Fear (2013): ‘If we had less imagination, we would feel more secure.’ Yes, there are real threats and enemies out there, but not as many as our active imagination produces. Alas, we can’t stop fantasticating if it’s the root of human cognition, and we wouldn’t want to give it up if we could. But can we turn that awesome power of imagination toward humanising ourselves and others?

Imagination recruits our natural empathy system and can amplify it. We see fear or joy in another person’s face, and we catch it like an emotional contagion. The actor has made a career of this natural human ability to recreate another’s feelings and perspectives within one’s self. Properly cultivated, this emotional mimicry can become ethical care, and art and artists play a crucial role in this cultivation.

I have played some sinister characters doing some ethically dubious things in dark storylines. I’m not someone who thinks art must be ‘moral’ per se. A lot of art with really overt moral pretensions is usually pretty bad art. Having said that, we could be making better use of the imagination, making genuinely smart and nuanced characters. A lot of contemporary entertainment seems to me to have lazy renderings of characters. There’s a kind of shorthand going on: a character beats up someone in one scene, then kisses his mom in the next to show complexity and ambiguity, but it all feels too simple and easy sometimes.

There’s a lot of contempt and cynicism in contemporary entertainment. The characters are contemptuous and cynical, and the impulses creating the characters are too. And there’s contempt for the audience: just give them crud. That’s always been a problem; I sound like an old-man moral scold. I’m all for the occasional mindless, nihilistic narrative, but the imagination is a hugely powerful tool and therefore weapon: if you’re gonna go morally dark or ambiguous, you’re gonna lacerate people, you better know why you are. You better be damn good at what you do, like Herman Melville good. It’s oddly easy to crank out something risky and edgy, we all think we know what that is, but most of it doesn’t really risk anything important, make real critiques of injustice or power. For sure: there’s really good stuff out there. But a lot of it’s weak, masquerading, performing its importance.

It’s really difficult to be ‘true’ as in ‘authentic’. Believe me, I know, I’m shooting for it myself and frequently missing the mark. It’s difficult to show how real friendships form or end, how real grief is processed, real horror and pain are inflicted and borne, so on.

You gotta be careful with the imagination. It matters how it’s wielded. There’s a lot of opportunity for critique, but hope too.

Acting is like a ‘laboratory of identity’ because the actor gets to try on many different selves. Some of them are sinister and some saintly, with all points in between. The movie industry and the arts generally are also large-scale laboratories of identity for audiences. Such power carries some responsibility. But all of us have this power of phantasia – in fact we can’t escape it – so it’s on all of us to be better actors and even directors of our stories, individual and shared.

To read more about the imagination, visit the Poiesis section on Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophical understanding and the arts.

Dorothy, Paul and a young Dorlie Fong dancing the cha cha during an encore performance. Courtesy of Dorlie Fong.

Dorothy, Paul and a young Dorlie Fong dancing the cha cha during an encore performance. Courtesy of Dorlie Fong.