Published in The Infinite Universe

1 day ago (Medium.com)

Modern scientism denies the existence of a soul because it fails to understand what is meant by the human soul from a philosophical perspective. Because religion adopts the concept of the soul for its own purposes, it is considered to exist within the realm of belief in the supernatural. Yet, the human soul is both a theological and a philosophical concept.

The Encyclopedia Britannica says that the soul is

the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being, that which confers individuality and humanity, often considered to be synonymous with the mind or the self.

There is no hint of religion or the supernatural in this definition. And it is reasonable to ask these four questions:

- Is there an immortal, immaterial aspect to a human person?

- Is that aspect a uniquely human essence or Soul?

- What is that essence?

- What happens to it upon the death of the body?

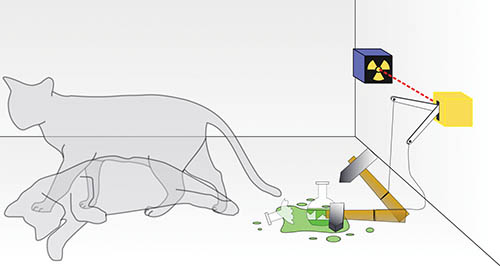

Quantum physics provides some answers to how a person’s essence could survive the death of the body. In fact, whole books have been written on Quantum Immortality.

Most authors have focused on the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics to construct a speculative narrative for human immortality based on world splitting.

It is sometimes called the Quantum Suicide thought experiment but need not include actual suicide. Examples include Robert Lanza of Biocentrism fame who argues that our consciousness cannot die but only appears to die because of quantum world splitting.

Even more fanciful mystical ideas have been tied to quantum theory, the only outcome being to enrich the authors at the expense of the scientifically and philosophically illiterate.

Such arguments as quantum immortality and the melding of eastern mysticism with quantum theory, however, are entirely speculative and make for better science fiction than philosophy.

The soul is fundamentally a body’s “lifeforce”. Indeed, the word for soul used in the New Testament is psuche which means “breath of life”.

From a modern physics perspective, inanimate bodies require two general things to be animate: energy and information. Energy is physical in that it has mass. Information, however, is immaterial. It and its cousin entropy have no mass.

Information gives matter its substantial form and is at the heart of how energy and matter self-organize into life.

If anything can be called “the breath of life” it is information, particularly information that enables emergent phenomena, that which is more than the sum of its parts.

But can the soul be considered to be made of information?

First let’s ask if people even have souls.

No-Self means no Soul

Many Buddhists claim to deny the existence of a Self or Soul. This is the concept of “no-self” or anatman in Sanskrit. This was a major departure from Hinduism, the ancestor religion of Buddhism.

On the other hand, Buddhists also largely believe in reincarnation, which supposes some element of a person survives death.

Buddhists don’t deny that a person’s consciousness can inhabit other bodies. Rather, No-Self derives from two beliefs (1) our inability to perceive anything that can be considered to be the Self and (2) the compound nature of what we think of as the Self.

No thought, perception, or physical object is part of the Self. What we consider to be the Self is an illusion based on a combination of constantly changing perceptions.

Then, do Buddhists believe that consciousness is the Soul or Self? No, because consciousness itself has no uniqueness and is universal.

Take as an example, if you say, “I see the red car”. Nowhere in this statement is an expression of Self. “I” is an artificially constructed ego that the brain uses to differentiate itself from the rest of the world. “To see” expresses the type of conscious experience, vision. And the red car is clearly not the self.

Conscious experience, sometimes called qualia, for example, what it is like to see something, may not distinguish you from anyone else. Thus, while you have existence, i.e., Dasein or “Thatness” your “Whatness” or Sosein has nothing to do with you! It is sort of like a movie playing in a theater with nobody watching.

Not all things in the universe are impermanent and changeable, however. As far as we know from quantum theory, information can change, but it is always conserved and recoverable.

Information conservation is a feature of all “complete” interpretations of quantum theory that assume that Schrodinger’s equation is fundamentally correct (including the MWI.)

Thus, the information content of the universe is changeless. It is merely the form it takes that changes. One can always apply processes to move that information forward and backward in time.

Thus, the information that becomes you, your body and your mind, always existed and always will exist.

Assuming that information conservation is an absolute law of the universe, i.e., quantum theory is “unitary”, then, we can answer the first question: is there an immortal, immaterial aspect of you, in the affirmative.

While Buddhists would deny that this immortal aspect carries personal uniqueness, they don’t deny it exists. Rather they claim it means you are just part of everything else.

Is our information theoretic essence a human soul?

To address the second question, that a unique essence or Soul exists, we have to look at Aristotle with a little help from Thomas Aquinas.

In order for the Self to be unique, it has to have distinguishing features which, in Aristotlean philosophy, are called its “substantial form”. These are features that are part of the object itself and not mere names that we give to those features.

More over, these are features that give a thing its identity. They are part of its essence.

While many modern philosophers, taking after Immanuel Kant, believe that substantial form is an illusion and that all properties of objects are subjective, that idea may be based on faulty premises derived from a classical, rather than quantum, mindset.

Unlike classical systems, where information is a bit of a fuzzy concept, quantum systems encode information within themselves in very specific ways (as sequences of qubits or quantum bits based on discrete quantum properties). Information is not subjective but objectively real and measurable.

This suggests that substantial form is real at the quantum level and, if it is real in the quantum realm, it must scale up to the human scale and beyond.

When you scale up, there is so much information in trillions of atoms that the substantial form is far too complex to put into human language.

Long before quantum theory, we developed broad linguistic categories in order to simplify those trillions of atoms, e.g., dog or cat instead of referring to the total information content of those creatures.

This abbreviated way of conceiving of the world made philosophers believe, mistakenly, that because those categories are artificial, there are no objective concrete categories!

There are but they are exceedingly complex.

The body manifests you as a whole, unique person but can’t be considered your essence or soul. Your essence must be much less.

Since the brain is part of the body, you need your body in order to have uniqueness. If your mind were to inhabit another body, it would have a whole new set of differentiating features. What would be left of the “you” you were before?

That is why I laugh at the concept of movies like Freaky Friday where people swap minds, as if that can be accomplished without physical changes. This is a good example of Platonism or Cartesian dualism.

What is actually being swapped here? All the unique neural circuitry so that the people still understand who they are, even their memories, is swapped but the brain continues to know how to operate the body, so that part hasn’t been swapped. The swapped part, however, is not only a swap of information. It is a physical modification of the brain.

The body needs to have physical substance to manifest in the world of course but its physical substance is not what makes it unique. Rather, it is its organization. Its organization is an immaterial aspect that includes the information encoded in DNA as well as life experiences that make each person unique.

This information not only encompasses the whole person or animal or plant, but has a unity and completeness that allows that person, animal, or plant to be a distinct individual.

All of this information is what makes you, you.

Therefore, the information content in you is immortal, immaterial and makes you unique.

What we have not established is whether there is one soul or many and whether the soul can be cut into pieces.

Is the soul divisible?

Aquinas rejected the common medieval notion that the soul is made of many parts. But it seems as if, by asserting that the soul is quantum information, we are supporting that the soul contains many, many parts.

Therefore, we need to restrict what we call the soul to an emergent property and not every quantum state of your body.

An emergent property is the embodiment of the motto E Plurbus Unum, from many one.

A good example is a tornado. A tornado is made a trillions upon trillions of air molecules. Each molecule has a position and velocity. Normally, in calm air, the positions of velocities of air molecules are random, but in a tornado they all align into a circular motion. How can that be? How can every molecule “know” which way to go?

The reason is because of temperature, pressure, and humidity differences that encourage the molecules to travel in a circular direction.

The tornado therefore has a unity that obtains from something external (warm moist air interacting with cool dry air and a wind shear caused by pressure differential).

Humans, animals, and plants are the same. Their components, down to the quantum level, have a unity that makes the individual emerge.

Yet, in the case of a tornado, what is the essence of that tornado as molecules drift in and out, it changes size and shape, and moves about?

Aquinas would say that the essence of the tornado is not everything about it, but rather its “tornadoness”. In other words, essence is generic not specific, and it has unity, not parts.

The same goes for human beings.

Thus the soul is not all your quantum information but a higher level derivative of it that, unlike individual qubits, has unity.

We observe phenomena like this in superfluids like liquid helium as well as superconductors. Many atoms or pairs of electrons suddenly behave like one big atom or pair of electrons. Unlike the tornado example such phenomena are true physical examples of from many one.

Entanglement, where multiple individual bits of matter and their qubits become connected to one another in a way that is subject to interpretation, is another example.

This is why the late Sir Roger Penrose proposed the idea that consciousness may be a quantum phenomenon. It appears to have an indivisible character reminiscent of quantum effects such as entanglement.

What separates us from the animals?

Aquinas further argued that at death all living things lose their soul except for human beings. Human beings, through their capacity for abstract thought, continue on.

Aquinas therefore considered the mind or intellect to be this essence. In other words, the action of the fundamental principle by which the human emerges versus something else like a cow is the intellect.

Modern neuroscience doesn’t give a clear answer but does point out that the mind appears to be an emergent process.

Aquinas supports a type of dualism in the Cartesian sense that he does not identify the mind with the body although he argues the mind is both inherent and separate from the body.

His concept of the mind is much smaller than Descartes’s or Plato’s.

Aquinas claims that animals do not have this dualism because they do not think. Neuroscience, however, contradicts him. Animals do think, but they lack the human capacity for abstraction.

This is a small matter, however, because Aquinas hits on a more important point which is that “it is clear that a human being is not a soul alone, but something composed of a soul and a body.”

He reasons that the soul alone is “human being” in a generic sense “but that a particular human being ── Socrates, say ── is not the soul”. (Summa Theologicae, Question 75, Article 4).

Here Aquinas carves a middle way between the generic consciousness of reincarnation and Plato’s assertion that the soul is a particular person.

He claims instead that human souls are unique to humans as a species but otherwise generic. Your soul and my soul are like two identical electrons. They are the same until placed in a body.

He is not however arguing for a “world soul”. Each soul belongs to a single person and can act like a diminished sort of person even without a body.

Can the soul be destroyed?

Aquinas argues that our soul is “incorruptible” meaning indestructible and unchangeable. He argued this because thinking is carried out “without a bodily organ”.

It is hard to understand what he means by this. A knee-jerk reaction would be to say that those medievals didn’t understand what the brain’s function was.

Later philosophers have in fact been frustrated with Aquinas because he wants to have his cake and eat it too. He wants the soul to need the body to be a person but also be separable from the body and still work like a mind.

His reasoning is that, because the mind can contemplate universal abstractions which are immaterial and non-sensory, the mind is an immaterial thing that contemplates immaterial things and therefore is completely separate from the body. Anything material like how an apple tastes or what a rainbow looks like is handled by the brain.

Because, he says, the mind operates on its own, with or without a body, therefore, it must be incorruptible. It must never die.

A modern paper gives a rough outline of Aquinas’ argument. It says that because consciousness is simple and unchanging it must be unable to fall apart into pieces and so must be incorruptible.

From a quantum perspective, this is not true. Any statement about incorruptibility is really a statement about conservation not indivisibility. Even stable fundamental particle or group of entangled particles such as electrons are simple and unchanging but nevertheless they can become other particles or can break their entanglement. Only the information content in them remains unchanging.

For Aquinas the incorruptibility of the soul is important because the soul is essential for salvation. If a human being were without a soul, he or she would have no hope beyond this life.

Do we remember anything of our past life after we die?

You would think from all this that Aquinas would argue that the soul, separated from the body, knows nothing, but he says that is not true.

When the soul is separated from the body, it understands the world differently, albeit no less muddled than a human would.

Here Aquinas distinguishes from sensory and intellectual knowledge. The disembodied soul loses all sensory knowledge upon death. This means that how things look, taste, smell, sound, and feel are no longer a part of it. That includes most memories.

If you have seen how a person with dementia such as Alzheimer’s slowly loses their memory, the soul does not recover those sensory memories after death.

It does retain, however, intellectual knowledge. For example, it would not remember what a person it saw in life looked like or felt like but would retain universal, abstract ideas about that person, in particular, knowledge of that other person’s soul.

Does the soul sleep after death?

Aquinas argues that the soul, meaning the intellect, is still “alive” after death. It continues to think, suffer, delight, make choices, and contemplate universals.

Aquinas is a survivalist in the philosophical sense of someone who believes the mind survives death intact.

A person who believes the soul sleeps until its body is resurrected is called a corruptionist.

Quantum immortality arguments based on the MWI are a kind of survivalist philosophy because they propose that consciousness cannot cease but they also don’t assume that the mind can separate from the body.

Quantum mystics such as Deepak Chopra are even more strongly survivalist and have claimed that the “quantum soul” can persist outside the body, existing nonlocally.

If this is true, then that would mean your soul persists as entangled quantum information spread over light years and also time.

For example, if you fell into a black hole, you would die and your matter and information, including any information theoretic soul, would be integrated into the singularity. According to the latest research on the black hole information paradox, your soul would be radiated back out over a googol years as Hawking radiation.

That Hawking radiation would remain entangled with the black hole.

If your soul is incorruptible, no matter what quantum processes are applied to it, it persists. Your mind could be composed of quantum information that is contained in matter that has been transformed into other particles and spread over lightyears.

I remain skeptical of this until I see a mathematical proof of exactly how an emergent process can survive any quantum transformation. This would require that the individual mind be a conserved property of the universe deriving from a symmetry group.

Aquinas, however, doesn’t concern himself with how the soul persists as our scientific age demands, only that it persists in a metaphysical sense.

While I haven’t read Chopra’s book on this idea, I will say that such an intellect would have to obey Aquinas’s restrictions in that it would have no sensory experience. It wouldn’t perceive itself as spread over light years because it would have no concept of space and time at all.

Many modern philosophers solve this problem by proposing panpsychism, that all matter is conscious to some extent. I think Aquinas would strongly disagree with that since it is very close to the idea of a universal soul that he fought hard to disprove.

Conclusion

We live in an age of materialism as well as Cartesian mind-body dualism, and we find it hard to escape from thinking about mechanisms, what things are made of, processes and so on.

While ours is the age of “how does it work?”, the past was an age of “what exists?”.

That is important because often when we try to answer how something works, we find that things we thought existed don’t and things we didn’t know existed, do.

For Aquinas and pre-Cartesian philosophers the world was divided into matter and form. It was perfectly reasonable for something immaterial such as a form to exist independently of any matter.

The big question for philosophy, particularly those who study Aquinas, who are called Thomists, has been: what is the interface between the material and the immaterial? How does that work?

Information theory, particularly quantum information theory with the addition of entanglement information and emergent phenomena, answers this question.

What isn’t clear is whether St. Thomas’s conclusions will survive being integrated into quantum theory. That would be a miracle.

Written by Tim Andersen, Ph.D.

·Editor for The Infinite Universe

1.2M views. Principal Research Scientist at Georgia Tech. The Infinite Universe (2020). andersenuniverse.com; https://timandersen.substack.com/