Lauren Carroll Harris on the Sober Spectacle of The Day After Trinity and The Strangest Dream

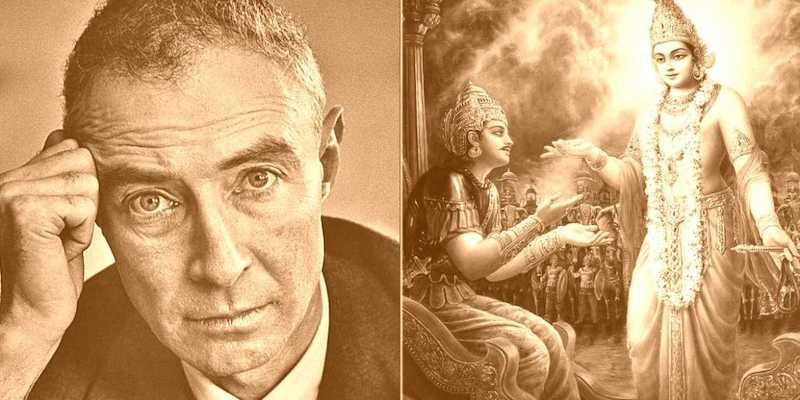

“Genius is no guarantee of wisdom,” says government official Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. It could be the blockbuster’s banner statement. Since the release of Nolan’s thrilling, bombastic film, the culture has been caught in the firestorm about how to explain the personality of the eloquent, esoteric J. Robert Oppenheimer and his creation of the first and only people-destroying atomic weapon to be used against civilians. Where Hollywood traffics in Oppenheimer’s ambiguity as a historical character, two small but potent nonfiction forebears ask a more pointed question: what is the responsibility of scientists to their societies?

The Day After Trinity (1981) and The Strangest Dream (2008) evacuate the mythical tropes of the tortured genius biopic that Hollywood loves to rehearse in films like The Imitation Game, Hawking, and A Beautiful Mind. Now enjoying a renaissance, the films are neither unforgiving nor hardline, but offer sharper moral clarity to the Oppenheimer dilemma, presenting a more complex (and condemning) portrait of the father of the atomic bomb: a patriot, philosopher-king, skilled public administrator, scientific collaborator with military and government, emotional naif, egotist, and polyglot.

Nolan’s story arcs towards Oppenheimer losing his naivete upon realizing that he has given humanity the power to destroy itself. Designed to wrap around each filmgoer’s own worldview and politics, the film is as politically open-ended as you might expect from a major blockbuster. In his press tour, Nolan articulated a more explicitly conservative stance that chimes both with the Great Man theory of history (another biopic favorite) and the Cold War military doctrine that justified the development and use of atomic arsenals against civilians.

“Is there a parallel universe in which it wasn’t him, but it was somebody else and that would’ve happened?” Nolan said in the New York Times. “Quite possibly. That’s the argument for diminishing his importance in history. But that’s an assumption that history is made simply by movements of society and not by individuals. It’s a very philosophical debate…. he’s still the most important man because the bomb would’ve stopped war forever. We haven’t had a world war since 1945 based on the threat of mutual assured destruction.”

That’s also the idea behind the official policy of the nuclear superpowers: deterrence. Horror, in other words, was necessary to prevent even greater horror. The very same doublethink led to Harry Truman’s honorary degree, conferred for ending the war.

How reluctant was Oppie? In Jon Else’s The Day After Trinity, a documentary originally made for public television in 1980, Oppenheimer’s collaborators deliver ambivalent, guilty testimony to a static, non-judgmental camera. Screening on the Criterion Channel, Else’s doc points to the great pleasure its subject took in being appointed the leader of the grandiose bomb project, with the cosmic job title of “Coordinator of Rapid Rupture.” The lens pans patiently across grainy, grayscale photographs that have the natural air of science fiction; the film feels more of a piece with Chris Marker’s La Jetee (1962) than a typical historical documentary. After all, Oppenheimer was not just the enabler of the weapons that could annihilate us all, but of the high-stakes hallmarks of modern spectacle itself. The awe-inspiring images of mushroom clouds over Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki are now instantly recognizable in the core visual grammar of contemporary entertainment and media. It’s hard to imagine an idea better suited to Nolan’s exalted, maximalist esthetic and his stories of obsessive male protagonists pressurized within towering patriarchal systems of power.

Oppenheimer positions the atomic bomb as the creation of a brilliant, creative personality. But The Day After Trinity revels in the administrative scale of the Los Alamos project necessary to make a mechanism to trigger, in a millionth of a second, a violent chain reaction with a flare brighter than a hundred suns. A walled city of six thousand staff, at a cost of $56 million. Seven scientific divisions: theoretical physics, experimental physics, ordinance, explosives, bomb physics, chemistry, and metallurgy. All of America’s industrial might and scientific innovation connected in this secret lab with its billions of dollars of military investment.

The Day After Trinity and The Strangest Dream evacuate the mythical tropes of the tortured genius biopic that Hollywood loves to rehearse.

“Somehow Oppenheimer put this thing together. He was the conductor of this orchestra. Somehow he created this fantastic esprit. It was just the most marvelous time of their lives,” says Freeman Dyson, a rather eccentric theoretical physicist who became Oppie’s colleague at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. “That was the time when the big change in his life occurred. It must have been during that time that the dream somehow got hold of him, of really producing a nuclear weapon.”

In this vision of the A-bomb narrative, Dyson posits that Oppie’s aims switched from finding out “the deep secrets of nature” to producing “a mechanism that works. It was a different problem, and he completely changed to fit the new role.” We begin to see more clearly a portrait of an outsider with a wild desire to be at the center. All the work the whiz kids were doing over the years was always designed to contribute to the war. (All the films remove Oppie’s more demonstrably radical tendencies, his belief in a world government, for instance, which he mentioned offhandedly in the New York Review of Books in 1966.)

The closest we get to Oppenheimer himself is his pale-eyed, doppelganger brother, Frank, who gives the impression of a visionary living in a purely abstract realm. He stammers a little when he speaks of the moment when he and Oppie heard on the radio of their great bomb in action. “Thank God it wasn’t a dud… thank God it worked… Up to then, I don’t think we’d really, I’d really, thought about all those flattened people.” He still seems stunned. If nothing else, Frank gives weight to the storytelling trope of scientists as hyperintelligent but flakey space cadets at a remove from the humanity of it all. “Treating humans as matter,” as Los Alamos collaborator Hans Bethe puts it appallingly. Another contributing scientist says he vomited and lay down in depression. “I remember being just ill,” he says. “Just sick.”

The doc swirls with clips accumulated from Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories, National Atomic Museum, American Institute of Physics, and Fox and NBC newsreels, while Paul Free’s authoritative narration hovers like an omniscient voice from the depths of the Cold War itself. Then, there is Oppie: a figure of stricken elegance in his rakish pork pie hat. Typical of documentaries constructed in a postmodern style, what it all means is never explicated. Ambiguity presides over clarity.

Most directive is Dyson’s testimony. “He made this alliance with the United States Army and the person of General Groves who gave him undreamed-of resources, huge armies of people, and as much money as he could possibly spend in order to do physics on the grand scale,” Dyson says with his flashlight perceptiveness. “We are still living with it. Once you sell your soul to the devil, there’s no going back on it.” Los Alamos, in this counternarrative, was not just an ivory tower but an irresistible paradise for genius-level scientists simply interested in new discoveries and mega-gadgets.Oppenheimer was not just the enabler of the weapons that could annihilate us all, but of the high-stakes hallmarks of modern spectacle itself.

Dyson is a dubious fellow to emerge as the truthteller, given the inconsistency of his own legacy. His unorthodox theories are worthy of their own Nolan-esque treatment. He advocated growing genetically modified trees on comets, so that they might land on other planets and create human-supporting atmospheres, and eventually became a climate change denier based on his distrust of mathematical models. But his intelligence is irrefutable, and his distance from the Manhattan Project gives him a guiltless perspective and authority absent in Oppie’s other colleagues. Dyson, a greater antagonist than can be found in any mere Marvel movie, diagnoses Oppie as the self-induced victim of a “Faustian bargain.”

“Why did the bomb get dropped?” Dyson asks, his tie a little too big, his combover a little too combed over. “It was almost inevitable. Simply because all the bureaucratic apparatus existed at that time to do it. The Air Force was ready and waiting… The whole machinery was ready.”

Dyson also refutes the refrain of Oppenheimer’s responsibility for the catastrophe. “It was no one’s fault that the bomb was dropped. As usual, the reason it was dropped was that nobody had the courage or the foresight to say no.” Dyson pauses to let this sink in, then looks down and wobbles his head tragically. “Certainly not Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer gave his consent in a certain sense. He was on a committee that advised the Secretary of War, and that committee did not take any kind of a stand against dropping the bomb.” This measured oral history is fatal to the view of Oppie as a gentle humanist.

Dorothy McKibben, who ran the Manhattan Project’s office, chimes in with crystal clarity: “I don’t think they would have developed that [bomb] to show at a garden party. I think they were going to do it.” In archival footage, General Leslie Groves plays the role of plainspoken pragmatist: “It would have come out, sooner or later, at a Congressional hearing, if nowhere else, just when we could’ve dropped the bomb if we didn’t use it. And then knowing American politics, you know as well as I do, if there had been an election fought on the basis of every mother whose son was killed after such-and-such a date, the blood is on the hands of the President.”

Through these testimonies, the convention of the conflicted scientist and the myth of an A-bomb created in self-defense give way to a mantra of winning the war, and winning quickly. Valuing American lives over other lives. Avoiding a bloody invasion of the Japanese mainland. Months before Hiroshima, orders had been given to leave several Japanese cities untouched, to provide virgin targets where the impact of the new bomb could be clearly seen. Afterwards, a scientific team from the US was sent to Japan to study the effects. Footage rolls, in The Day After Trinity, of news clips of hospitalized burn victims.This measured oral history is fatal to the view of Oppie as a gentle humanist.

In films on the Manhattan Project, questions of conscience are commonly seen through the assenting viewpoint—that of the scientists who continued to work on the bomb, even after Hitler’s defeat. One essential perspective is obscured, black-holed in subterfuge, even. Physicist and European refugee Joseph Rotblat made crucial discoveries in the fission process, and went on to specialize in nuclear fallout. He moved to Los Alamos in 1944 but defected from the project on grounds of conscience upon learning that the Nazis could not build such a bomb. He was the only scientist to turn his back.

“If my work is going to be applied, I would like myself to decide how it is applied,” Rotblat says in the 2008 Canadian documentary The Strangest Dream. Streaming on the National Film Board of Canada’s platform, the film traces his renunciation of A-bomb development and his role in the Pugwash Conferences, where scientists and statesmen gathered to discuss the reversal of nuclear proliferation. The film renders a fairly straight treatment of its quiet subject, with the visually rich backing of a vertiginous collage of disparate forms, including spooky Cold-War era footage and clips of the Trinity mushroom cloud. Oppie is not in the film, but the narrative takes place in the fissures he helped wrench open; he lurks like an ever-present ghost behind the character of Rotblat, who stands as his angelic nemesis as he tries to transform physics into a humanitarian project. Like Oppenheimer, Rotblat was also accused of espionage, but he was eventually awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his contributions to the disarmament campaign.

Notably, Rotblat is entirely absent from Oppenheimer, despite being described as a brilliantly offbeat individual—a “mad Polish scientist”—by a former student in The Strangest Dream. It’s a curious historical erasure and a missed chance for a dramatic clash. Then again, perhaps Rotblat is too steady and untragic, incorruptible and unmemeable for his own big moment, let alone the blockbuster treatment. Oppie’s genius wasn’t just in his Faustian bargain but in the way that he spoke and the way he held himself, quoting Hindu philosophy and smoking till the end of time. I suppose film culture is more interested in the flawed, tortured luminary than the staunch, principled dissenter or the morally engaged scientist.

Prosecuting the melancholic drama of the ingenuous mastermind requires substantial historical selectivity. Most cinema narratives hew to the oft-cited rationale for the A-bomb’s development: its function as a deterrent to a Nazi explosive. But in his essay “Leaving the Bomb Project,” Rotblat wrote, “Groves said that, of course, the real purpose in making the bomb was to subdue the Soviets… Until then I had thought that our work was to prevent a Nazi victory, and now I was told that the weapon we were preparing was intended for use against the people who were making extreme sacrifices for that very aim.” With more than a dash of elegiac melancholy, the working thesis of The Strangest Dream is that Rotblat’s moral strength insulated him against Oppie-style tragedy.

Insofar as the The Strangest Dream and The Day After Trinity position the Manhattan Project as an unholy alliance of physics and the openly violent arm of the state, they do so via the absent presence of Oppenheimer, who, flush with government cash, personifies the uneasy collision of science and military. Today’s ventures in AI offer the same science-ethics conundrum, and we don’t seem to be any closer to resolving it than at the moment of Oppenheimer’s mythic quandary. Looking at the images of the Los Alamos exertions, you can almost faintly hear the words of today’s STEM bros: disruption, innovation, brilliance. Wondrous and diabolical, the A-bomb is presented in these documentaries as the freakish outcome of public-bureaucratic entrepreneurialism. (They are weaker on the tangled history of superpower competition and atomic technology.) It all depends, of course, on what humans do with the technology we develop.

If there’s such a thing as sober, mournful spectacle, these films manifest it.

Given what we know about capitalist society at present, things aren’t exactly looking up. Just a decade after The Day After Trinity, the Cold War victory lap was being run at the box office. A new, end-of-history generation of studio filmmakers was writing a euphoric, Fukuyama-esque version of reality into pop-culture lore: in blockbusters like Independence Day (1996), The Core (2003), and Armageddon (1998), American pluck saves humanity from wholesale destruction; anxiety surrounding US dominance over the international order is undetectable, and the US military is either prominent or necessary. Before them all, The Day After Trinity suggested that technology’s triumph is the very crux of the problem.

Today, Oppenheimer reifies a political crisis—superpower competition for atomic arsenal—as a conundrum of personality, tech, and naive genius, even as it centers the wild fraternity of science, military, and government vital to create the A-bomb. But the political arrangement of power and resources seems like more of an objective, inevitable fact about the world in The Day After Trinity and The Strangest Dream. If there’s such a thing as sober, mournful spectacle, these films manifest it.

Oppenheimer is long gone, but his legacy—the capacity of a self-destroying humanity, and the late-capitalist spectacle of that mushroom cloud’s bright flash of light—lingers. He did not sign the Einstein-Russell Manifesto against nuclear war. He never apologized for his role in bringing the bomb to life. Atomic technology is now standard. The world’s nuclear powers currently possess an estimated 12,512 active warheads. More than enough to wipe out the planet.

Lauren Carroll Harris

Lauren Carroll Harris has been published in LA Review of Books, Sydney Review of Books, Lit Hub, The Baffler, Mubi Notebook, Cineaste, and the Open Secrets book anthology (Giramondo) among others. She is the founding curator of the Prototype experimental film platform and has programmed moving image for the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial and Carriageworks. She has a PhD in film studies.