By Teju Ravilochan (contributing editors: Vidya Ravilochan and Colette Kessler)

Apr 4, 2021 (gatherfor.medium.com)

Author’s Note: This is a complete revision of the post originally titled “Maslow Got It Wrong.” My earlier version included inaccuracies, as some readers pointed out, like the assumption Maslow depicted his theory in a pyramid shape. I have documented and attempted to correct these errors in this companion post called What I Got Wrong: Revisions to My Post About Maslow and the Blackfoot. I’ve updated the post you’ll read below, so it is more focused on what we can learn from the Blackfoot and from other Native cultures. I have retitled this post to reflect this emphasis more clearly.

Some months ago, I was telling my friend and GatherFor Board Member Roberto Carlos Rivera that I had come across unpublished papers by Abraham Maslow suggesting changes to his famous Hierarchy of Needs. Roberto, Executive Director of Alliance for the 7th Generation, was familiar with the subject and turned me on to something else I didn’t know: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs may have been inspired by the Siksika (Blackfoot) way of life. In reading follow-up materials he sent me, I learned Maslow spent six weeks living at Siksika — which is the name of the people, their language, and the Blackfoot Reserve — in the summer of 1938. His time there upended some of his early hypotheses and possibly shaped his theories. While I initially came to believe Maslow appropriated and misrepresented the teachings of the Blackfoot, I have learned that this narrative, while held by some, may not be accurate even according to Blackfoot scholars. Yet what has been far more valuable for me in this inquiry was learning what Maslow witnessed at Siksika. Whereas mainstream American narratives focus on the individual, the Blackfoot way of life offers an alternative resulting in a community that leaves no one behind.

Research Methodology

Ryan Heavy Head (also known as Ryan FirstDiver) and the late Narcisse Blood, members of the Blackfoot Nation, received a grant from the Canadian Government’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council to research Blackfoot influences on Maslow. Their lectures summarize their findings and are stored in the Blackfoot Digital Library. Dr. Cindy Blackstock — a member of the Gitxsan First Nation tribe, a professor at McGill, and Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society — has conducted similar research. My primary investigation into this topic involved watching Blood and Heavy Head’s lectures; reading the works of and corresponding with Cindy Blackstock; speaking to and reviewing the writings and podcasts of the world’s foremost Maslow expert, Dr. Scott Barry Kaufman; speaking to Ryan Heavy Head on the phone; and consulting the sources cited at the end of this article.

What Maslow Encountered at Siksika

According to Blood and Heavy Head’s lectures (2007), 30-year-old Maslow arrived at Siksika along with Lucien Hanks and Jane Richardson Hanks. He intended to test the universality of his theory that social hierarchies are maintained by dominance of some people over others. However, he did not see the quest for dominance in Blackfoot society. Instead, he discovered astounding levels of cooperation, minimal inequality, restorative justice, full bellies, and high levels of life satisfaction. He estimated that “80–90% of the Blackfoot tribe had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in 5–10% of his own population” (video 7 out of 15, minutes 13:45–14:15). As Ryan Heavy Head shared with me on the phone, “Maslow saw a place where what he would later call self-actualization was the norm.” This observation, Heavy Head continued, “totally changed his trajectory.” (For the reader wondering what self-actualization is, Maslow offered this definition, influenced by Kurt Goldstein, in his 1943 paper: “This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.” The word itself does not exist in the Siksika language, but the closest word is niita’pitapi, which Ryan Heavy Head told me means “someone who is completely developed, or who has arrived.”)

Deeply curious about the reason for the stark difference between Blackfoot culture and his own culture, Maslow sought out positive deviants, or unusually successful individuals. He started with the wealthiest members of the Blackfoot tribe. He discovered that “for the Blackfoot, wealth was not measured by money and property but by generosity. The wealthiest man in their eyes is one who has almost nothing because he has given it all away” (Coon, 2006). Maslow witnessed a Blackfoot “Giveaway” ceremony in his first week at Siksika. During the Giveaway, members of the tribe arranged their tipis in a circle and publicly piled up all they had collected over the last year. Those with the most possessions told stories of how they amassed them and then gave every last one away to those in greater need (Blood & Heavy Head, 2007, video 7 out of 15, minutes 13:00–14:00). By contrast, as shared by Maslow’s biographer Edward Hoffman, Maslow observed different qualities in members of his own culture:

To most Blackfoot members, wealth was not important in terms of accumulating property and possessions: giving it away was what brought one the true status of prestige and security in the tribe. At the same time, Maslow was shocked by the meanness and racism of the European-Americans who lived nearby. As he wrote, “The more I got to know the whites in the village, who were the worst bunch of creeps and bastards I’d ever run across in my life, the more it got paradoxical.”

Maslow continued his investigation by looking into negative deviants. He was curious how the Blackfoot might deal with lawbreakers without the strategy of dominance that he’d seen in his own culture. He found that “when someone was deviant, [the Siksika] didn’t peg them as deviant. A person who was deviant could redeem themselves in society’s eyes if they left that behavior behind” (Blood & Heavy Head, 2007, video 7 out of 15, minutes 15:44–16:08).

Maslow then wondered whether the answer to producing high self-actualization might lie in child-rearing. He found that children were raised with great permissiveness and treated as equal members of Siksika society, in contrast to a strict, disciplinary approach found in his own culture. Despite having great freedom, Siksika children listened to their elders and served the community from a young age (ibid, minutes 16:35–17:07).

According to Heavy Head, witnessing the qualities of self-actualization among the Blackfoot and diving into their practices led Maslow to deeper research into the journey to self-actualization, and the eventual publishing of his famous Hierarchy of Needs concept in his 1943 paper.

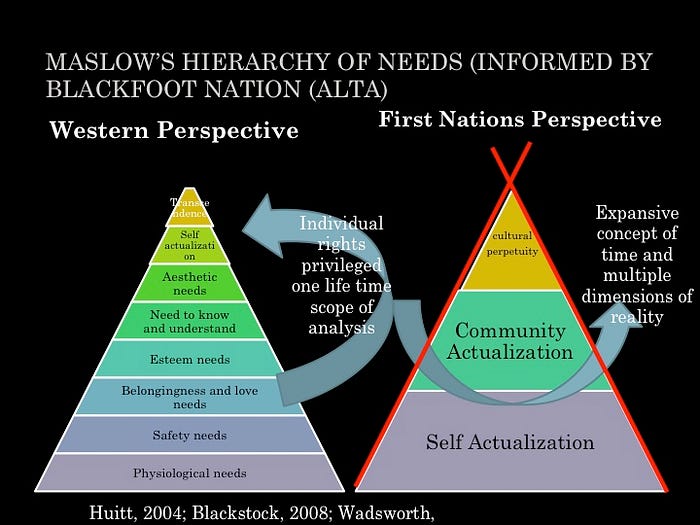

Differences Between Maslow’s Theories and Blackfoot Beliefs

Ryan Heavy Head shared with me that, while there are strong belief systems and long standing traditions in place, the Blackfoot don’t have a “model” for their worldview, neatly codified in a paper like Maslow’s. But to help explain the different emphases of the Western worldview and the views of First Nations, Dr. Cindy Blackstock, herself a member of the Gitxsan tribe who interviewed members of the Blackfoot Nation, created the illustration below (Michel, 2014):

Blackstock makes clear that there is great diversity among First Nations, but the above diagram captures some of the similarities she’s found in her study of them, including the Blackfoot. I summarize my understanding of her diagram below.

Self-Actualization

Maslow appeared to ask, “how do we become self-actualized?”. Many First Nation communities, though they would not have used the same word, might be more likely to believe that we arrive on the planet self-actualized. Ryan Heavy Head explained the difference through the analogy of earning a college degree. In Western culture, you earn a degree after paying tuition, attending classes, and proving sufficient mastery of your area of study. In Blackfoot culture, “it’s like you’re credentialed at the start. You’re treated with dignity for that reason, but you spend your life living up to that.” While Maslow saw self-actualization as something to earn, the Blackfoot see it as innate. Relating to people as inherently wise involves trusting them and granting them space to express who they are (as perhaps manifested by the permissiveness with which the Siksika raise their children) rather than making them the best they can be. For many First Nations, therefore, self-actualization is not achieved; it is drawn out of an inherently sacred being who is imbued with a spark of divinity. Education, prayer, rituals, ceremonies, individual experiences, and vision quests can help invite the expression of this sacred self into the world. (As some readers have commented, this concept appears in other belief systems, such as Paulo Freire’s challenge to the “banking concept of education” and the Buddhist notion that all beings contain Buddha-nature.)

Community Actualization

As Maslow witnessed in the Blackfoot Giveaway, many First Nation cultures see the work of meeting basic needs, ensuring safety, and creating the conditions for the expression of purpose as a community responsibility, not an individual one. Blackstock refers to this as “Community Actualization.” Edgar Villanueva (2018) offers a beautiful example of how deeply ingrained this way of thinking is among First Nations in his book Decolonizing Wealth. He quotes Dana Arviso, Executive Director of the Potlatch Fund and member of the Navajo tribe, who recalls a time she asked Native communities in the Cheyenne River territory about poverty:

“They told me they don’t have a word for poverty,” she said. “The closest thing that they had as an explanation for poverty was ‘to be without family.’” Which is basically unheard of. “They were saying it was a foreign concept to them that someone could be just so isolated and so without any sort of a safety net or a family or a sense of kinship that they would be suffering from poverty.” (p. 151)

Ryan Heavy Head explains that such communal cooperation is especially important for the Blackfoot because of their relationship to place, something Maslow entirely omitted in his theories:

the one thing that [Maslow] really missed was the Indigenous relationship to place. Without that, what he’s looking at as self-actualization doesn’t actually happen. There’s a reason people aren’t critical of their tribe: you’ve got to live with them forever.

In other words, having your life bound up with those around you for its whole duration can support creating a culture of generosity, trust, and cooperation, rather than one of inequality and individualism. Being in conflict with permanent neighbors, while also living in such a communal culture, can prove costly and stressful. Learning to cooperate, forgiving wrongdoing, and pursuing the sharing of resources and wisdom make life much more tolerable in these conditions.

Cultural Perpetuity

The skillfulness to nourish a community-wide family, keep each person fed, live in harmony with the land, and minimize internal and external conflicts is handed down from generation to generation in First Nations. Because knowledge can vanish as people pass on, each generation sees it as their responsibility to perpetuate their culture by adding to the tribe’s communal wisdom and passing on ancestral teachings to children and grandchildren. As Cindy Blackstock (2019) explains:

First Nations often consider their actions in terms of the impacts of the “seven generations.” This means that one’s actions are informed by the experience of the past seven generations and by considering the consequences for the seven generations to follow.

Many First Nations have developed both formal rituals and informal apprenticeships for the transfers of wisdom from elders to youngsters to ensure the community is able to support self-actualization and community-actualization in perpetuity.

As Blackfoot scholar Billy Wadsworth (of the Blood, or Kanai Tribe) summarizes in dialogue with Cindy Blackstock (2011), Maslow did not “fully situate the individual within the context of community.” If he had done so, and also more deeply integrated the Blackfoot perspective, “the model would be centered on multi-generational community actualization versus on individual actualization and transcendence.”

Maslow himself may have agreed with this critique. Scott Barry Kaufman (2020) shares an excerpt from an unpublished Maslow essay from 1966, 23 years after he published his paper on the Hierarchy of Needs, called “Critique of Self-Actualization Theory”,

self-actualization is not enough. Personal salvation and what is good for the person alone cannot be really understood in isolation. The good of other people must be invoked as well as the good for oneself. It is quite clear that purely inter-psychic individualist psychology without reference to other people and social conditions is not adequate.

What else emerges when we see the individual as deeply situated in community?

Circles, Not Triangles

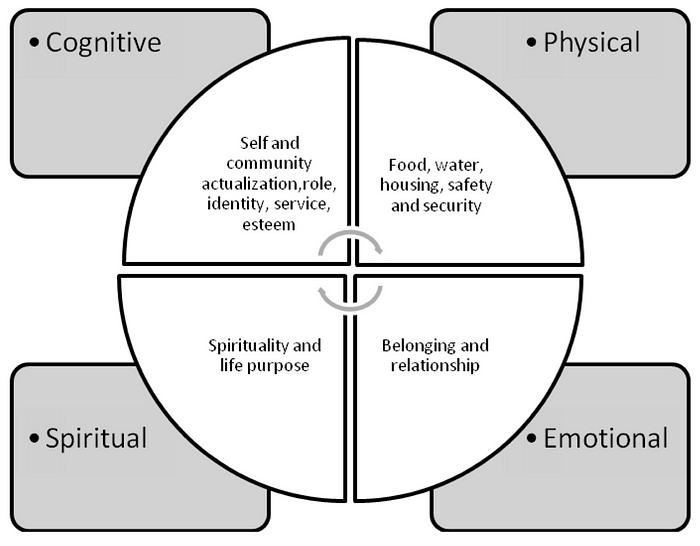

The triangular models above suggest that there’s a place to start meeting our needs and a place we end up. But is it true that our needs follow Maslow’s hierarchy of “prepotency”, where some needs consistently take priority over others? Maslow (1943) himself indicates there are many exceptions to his hierarchy and Blackstock (2011) agrees, citing Seneca First Nation member and psychologist Terry Cross:

Cross (2007) argues that human needs are not uniformly hierarchical but rather highly interdependent […] [P]hysical needs are not always primary in nature as Maslow argues, given the many examples of people who forgo physical safety and well-being in order to achieve love, belonging, and relationships or to achieve spiritual or pedagogical objectives. The idea of dying for country is an example of this as men and women fight in times of war.

Blackstock represents Cross’ ideas in the circular model below:

This circular model reveals thinking in line with many First Nations: depending on the situation, the order in which our needs must be met is subject to change. A circular model captures the inter-relatedness of our needs and helps highlight that we can experience needs simultaneously and in changing order. This way of viewing needs makes more sense when seeing an individual as deeply rooted in a community, especially because a community is capable of meeting multiple needs in parallel. While one individual is cooking, another may be keeping children safe, while another may be negotiating peace with people from other tribes.

When we organize a society as though each individual is primarily responsible for meeting their own needs, we may see results like Maslow predicted in his 1943 paper:

In actual fact, most members of our society who are normal, are partially satisfied in all their basic needs and partially unsatisfied in all their basic needs at the same time. A more realistic description of the hierarchy would be in terms of decreasing percentages of satisfaction as we go up the hierarchy of prepotency, For instance, if I may assign arbitrary figures for the sake of illustration, it is as if the average citizen is satisfied perhaps 85 per cent in his physiological needs, 70 per cent in his safety needs, 50 per cent in his love needs, 40 per cent in his self-esteem needs, and 10 per cent in his self-actualization needs.

In this hierarchical view and the subsequent execution of it in society, it’s rare to see individuals who have met their needs. Here’s Maslow again:

We shall call people who are satisfied in these needs, basically satisfied people […] Since, in our society, basically satisfied people are the exception, we do not know much about self-actualization, either experimentally or clinically.

But Maslow seemed to discover that basically satisfied people were the norm at Siksika, where community was primarily responsible for meeting the needs of its members.

Why Haven’t We Heard About The Blackfoot Worldview Before?

Though Maslow saw full bellies, low-inequality, and rates of self-actualization at 80–90%, why didn’t he alert the world to all we could be learning from the Blackfoot? He clearly held them in high regard, as he indicated in journals and in his biography.

It’s possible that Maslow may have faced dismissal if he had publicized Blackfoot teachings. Dr. Richard Katz, author of Indigenous Healing Psychology: Honoring the Wisdom of First Peoples, Harvard professor, and personal friend of Maslow’s speaks to this point in a podcast conversation with Scott Barry Kaufman (minutes 28:50–32:20). He says he never spoke directly with Maslow about this, but postulates that Maslow may have been concerned that elevating Siksika teachings might diminish the validity of the ideas he was putting forth. Such barriers to Indigenous contributions have remained in academia until today (Blackstock, 2019).

Despite the fallibility of our mainstream institutions, publicly challenging prevailing worldviews is risky business. Galileo’s elevation and defense of the Copernican heliocentric solar system, for example, led to his being labeled a heretic by the Catholic Church and placed under permanent house arrest.

By offering compelling alternatives, Indigenous worldviews pose a threat to our status quo. Lakota Medicine Man John Fire Lame Deer offers one poignant contrast between the world he grew up in and the world of “the white man”:

Before our white brothers came to civilize us we had no jails. Therefore we had no criminals. You can’t have criminals without a jail. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves. If a man was so poor that he had no horse, tipi or blanket, someone gave him these things. We were too uncivilized to set much value on personal belongings. We wanted to have things only in order to give them away. We had no money, and therefore a man’s worth couldn’t be measured by it. We had no written law, no attorneys or politicians, therefore we couldn’t cheat. We really were in a bad way before the white men came, and I don’t know how we managed to get along without these basic things which, we are told, are absolutely necessary to make a civilized society. (Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions, p. 70)

Consider Lame Deer’s description and what Maslow witnessed at Siksika. Then consider the repetition of the idea that “the United States of America is the greatest country in the world” despite the facts that one in four US households experience food insecurity, 4 in 10 Americans can’t afford a $400 emergency, the richest 0.1 percent make 196x as much as the bottom 90 percent, and with 40 million in poverty, the US may be the most unequal nation in the Western world.

Precisely for whom is the United States the greatest country in the world?

The wealthiest Americans, unlike the Blackfoot during the Giveaway Ceremony — devote the smallest portion of their income to supporting those in need. As Ken Stern writes in The Atlantic:

In 2011, the wealthiest Americans — those with earnings in the top 20 percent — contributed on average 1.3 percent of their income to charity. By comparison, Americans at the base of the income pyramid — those in the bottom 20 percent — donated 3.2 percent of their income. […] Some experts have speculated that the wealthy may be less generous [than other classes] — that the personal drive to accumulate wealth may be inconsistent with the idea of communal support.

Since its inception, mainstream US culture has consistently failed to meet the basic needs of so many of its people. Who wins when, despite this shortcoming, we tell tales of American greatness? Who is left out?

Waking up from Our American Dream

As Seneca First Nation member and psychologist Terry Cross defines it in this keynote presentation, “culture is one group or people’s preferred way of meeting their basic human needs.” The American Dream tells us that we meet our basic needs by working hard to “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.” That way, we become free from having to depend on anyone else.

Who benefits from this story being told? Is it even true? As Daniel Suelo says in The Man Who Quit Money, “There’s not a creature or even a particle in the universe that’s self-sufficient. We’re all dependent on everybody else” (p. 133). Who sewed the clothes you’re wearing right now? How many materials from how many different parts of the world are inside the device you’re reading this post on? How many hands touched the food you ate for lunch on its way to your table? How many living beings participated in the creation of your home, in your education, and in your emotional state? Even if you purchased these goods with money you earned, you are relying on a community to care for you. Our lives are inextricably tied up with one another. Indigenous communities offer us an example of what is possible when we embrace this reality.

Because it has affected us all and exposed fissures in our structural underpinnings, this pandemic may be our moment to interrupt our old story. It’s prompted us to embrace previously heretical ideas like reparations, universal basic income in the form of stimulus checks, and mutual aid. This is our moment to step out of our lonely struggle to fend for ourselves, a story maintained by those winning in the status quo. This is our moment not to create something new, but to return to an ancient way of being, known to the Blackfoot, the Lakota, the Natives of the Cheyenne River Territory, and other First Nations. It’s a story that leaves no one without family: a story in which we begin by offering each other belonging, and continue by teaching our descendants how we lived: together.

About the Author

For years, I’ve been wrestling with the American Dream — especially the part that tells us we should all be self-made. My parents immigrated to the US from India with $200 in their pockets. While they worked hard, they might not have been able to navigate life in a brand-new country if my Uncle Suresh hadn’t given them a place to stay or if a kind stranger named Dr. Bob Selker had made a call that landed my dad his first job at a hospital in Denver. My own family’s experience taught me that no one makes it on their own. My belief that no one makes it on their own led to creating GatherFor. We organize and resource teams of neighbors experiencing unemployment, housing and food insecurity, and other socioeconomic challenges to support each other like a family would. We provide them direct cash assistance and workshops as requested on the way to supporting them cultivate a “neighborhood safety net.” We’re currently piloting in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and you can learn more at gatherfor.org and support our direct cash assistance efforts here if you’d like.

Acknowledgements

Writing this post, especially after receiving a great deal of public feedback, involved multiple drafts, rewrites, and conceptual reorientations. You can see another post detailing my earlier inaccuracies and corrections here. I am sincerely grateful to Colette Kessler and Vidya Ravilochan for serving as thought partners and diligent editors for multiple drafts of this post. I also want to thank Roberto Rivera for teaching me about many of the concepts presented here; Ryan Heavy Head for his phone call with me and reviews of this draft; Scott Barry Kaufman for compassionate corrections to nuances about Maslow’s work; and Abby Nimz, Kamasamudram Ravilochan,

Etan Kerr-Finell, and

Sheryl Winarick for feedback. This post would not be possible without the work of Ryan Heavy Head and Narcisse Blood for telling the story of Maslow’s time at Siksika and Cindy Blackstock for the development of her Breath of Life Theory. Lastly, I want to convey my deepest thanks to the Siksika and other Native peoples for sharing the teachings that I believe we have so much to learn from.

Sources:

Barney, Anna. (2018, May 22). 40% of Americans can’t cover a $400 emergency expense. CNN Money.

Blackstock, Cindy. (2011). The Emergency of the Breath of Life Theory. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8, 1.

Blackstock, Cindy. (2019). Revisiting the Breath of Life Theory. British Journal of Social Work, 49, 854–849.

Blood, N., & Heavyhead, R. (2007). Blackfoot influence on Abraham Maslow (Lecture delivered at University of Montana). Blackfoot Digital Library. Accessed 25 April 2021.

Cross, T. (2007, September 20). Through indigenous eyes: Rethinking theory and practice. Paper presented at the 2007 Conference of the Secretariat of Aboriginal and Islander Child Care in Adelaide, Australia.

Coon, D. (2006). Abraham H. Maslow: Reconnaissance for eupsycia. In D.A. Dewsbury, L.T. Benjamin Jr. & M. Wertheimer (Eds). Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology, Vol. 6 (pp. 255–273). Washington, D.C. & Mahwah, N.J.: American Psychological Association and Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Government of Canada (2007, December 17). Rediscovering Blackfoot Science, How First Nations Helped Develop a Keystone of Modern Psychology. Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Accessed on 26 April 2021.

Kaufman, S.B. (2019). Who Created Maslow’s Iconic Pyramid? Scientific American. Accessed on 24 April 2021.

Kaufman, S.B (Host), & Katz, R (Guest). (2019, January 10). Honoring the Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples with Richard Katz [Audio podcast episode]. In The Psychology Podcast. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

Kaufman, S.B. (2020). Transcend. TarcherPerigee.

Feigenbaum, K. D., & Smith, R. A. (2020). Historical narratives: Abraham Maslow and Blackfoot interpretations. The Humanistic Psychologist, 48(3), 232–243.

Lame Deer, J. F., & Erdoes, R. (1994). Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions. Simon & Schuster.

Lokensgard, K.H. (2014). Blackfoot Nation. In: Leeming D.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer, Boston, MA.

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. Accessed on 27 April 2021.

Michel, K. L. (2014). Maslow’s Hierarchy Connected to Blackfoot Beliefs. Accessed on April 2, 2021.

Silva, Christina. (2020, September 27). Food Insecurity in the U.S. By the Numbers. NPR.

Villanueva, Edgar. (2018). Decolonizing Wealth. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.