Views from the Real World

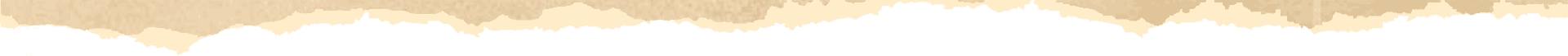

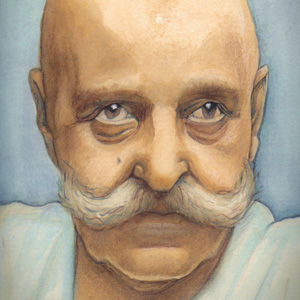

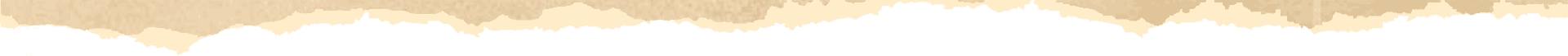

G.I. Gurdjieff

First published in 1975, this book has established itself as an authentic source for those interested in Gurdjieff’s ideas and his approach to practical “work on oneself”.

(Goodreads.com)

First published in 1975, this book has established itself as an authentic source for those interested in Gurdjieff’s ideas and his approach to practical “work on oneself”.

(Goodreads.com)

Ebayed • Jan 18, 2024 • Explore the life and teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff, a mystic and spiritual teacher whose profound philosophy, known as the Fourth Way, has inspired seekers of self-realization. This video delves into key aspects of Gurdjieff’s life, his transformative teachings, and the impact of The Work on spiritual development. ? Key Points: Gurdjieff’s early life in the Russian Empire. The Fourth Way: A unique spiritual teaching integrating mysticism, psychology, and esotericism. The Work: Emphasizing self-observation, self-awareness, and breaking free from mechanical behavior. Influences from Eastern philosophies and extensive travels in the East. Notable books like “Meetings with Remarkable Men” and “Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson.” The establishment of spiritual communities and schools. Gurdjieff’s lasting legacy and diverse interpretations of his teachings.

Dec 25, 2023 (mitch-horowitz-nyc.medium.com)

One of the most seminally important and enigmatic spiritual figures of the twentieth century was Greek-Armenian philosopher G.I. Gurdjieff (1866–1949). His essential teaching is that man lives in a state of sleep — not metaphorically but actually.

Human existence, the teacher observed, is not only passed in sleep but man himself is in pieces, at the passive bidding of his three brains or centers: thinking, emotional, and physical, all of which function in disunity leaving a “man-machine” incapable of authentic activity.

“Man cannot do,” Gurdjieff said. He meant this in the fullest sense.

Nearly all of Gurdjieff’s statements — including his 1950 literary giant Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson — were intended to disrupt rote thought. He instructed that the magisterial allegory be read three times.

Author P.L. Travers, best known for the Mary Poppins books, noted aptly, “In Beelzebub’s Tales, soaring off into space, like a great, lumbering, flying cathedral, Gurdjieff gathered the fundamentals of his teaching.”

There is no neat summarizing the breadth of Gurdjieff’s system, which extended to sacred dances, self-observation, rigorous and challenging training and confrontation with obstacles, and what might be considered a cosmological-existential-spiritual psychology, explored by one of his greatest students, P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947), who produced an invaluable record of his experiences with Gurdjieff, In Search of the Miraculous, posthumously published in 1949. A brief, though daunting, analysis also appears in Ouspensky’s The Psychology of Man’s Possible Evolution, published in 1950.

Appearing in Russia shortly before World War I, Gurdjieff assembled a remarkable circle of students, some of whom followed him in a harrowing escape across the continent amid the chaos and danger of war and revolution.

A sense of Gurdjieff’s relationship to his students and manner of teaching appears in an episode from Fritz Peters’ haunting and powerful 1964 memoir Boyhood with Gurdjieff.

In Peters’ book, the author recounts the commitment Gurdjieff exacted from Fritz at age eleven. The young adolescent met Gurdjieff in June 1924 when he was sent to spend the summer at the teacher’s school, the Prieuré, a communal estate in Fontainebleau-Avon outside of Paris.

Speaking to Fritz on a stone patio one day, Gurdjieff banged the table with his fist and asked, “Can you promise to do something for me?” The boy gave a firm, “Yes.” The teacher gestured to the estate’s vast expanse of lawns. “You see this grass?” he asked. “Yes,” Fritz said again. “I give you work. You must cut this grass, with machine, every week.”

Fritz agreed — but that wasn’t enough. Gurdjieff “struck the table with his fist for the second time. ‘You must promise on your God.’ His voice was deadly serious. ‘You must promise that you will do this thing no matter what happens.’” Fritz replied, “I promise.” Again, not enough. “Not just promise,” Gurdjieff said. “Must promise you will do no matter what happens, no matter who try stop you. Many things can happen in life.”

Fritz vowed again.

Very soon, in the lives of Fritz and his teacher, something seismic and upending did occur. Gurdjieff suffered a severe car accident and for several weeks laid in a near-coma recovering at the Prieuré.

Fritz, feeling that the whole thing seemed almost foreordained, honored his commitment to keep mowing the lawns. But he met with stern resistance. Several adults at the school insisted that the noise would disturb Gurdjieff’s convalescence and could even result in the master’s death.

Fritz recalled how unsparingly the promise had been extracted and how fully it had been given. He refused to relent. He kept mowing — no one physically stopped him. One day while Fritz was cutting the lawns, he spied the recovering master smile at him from his bedroom window.

One of the greatest benefits students receive from Gurdjieff’s teaching (to which I can personally attest) is how it punctures, immediately and sometimes devastatingly, one’s cherished images of self.

We in the modern West are suffused with contradictions. People are filled with puffed up views of themselves. They are also filled with the opposite. But take one person and give him or her an unfamiliar task at an inconvenient hour and you will see how powerful or special we are. Not very.

Gurdjieff constantly pushed people to surpass their limits of perceived strength. In his posthumous memoir, Meetings with Remarkable Men, the teacher described episodes from when he and a band of students fled civil war-torn Russia. In an epilogue, “The Material Question,” he addressed their need for money.

In the summer of 1922, after a dangerous flight across Eastern Europe, Gurdjieff and his students reached Paris with razor-thin resources. Procuring an estate, the Prieuré, to function as living quarters and school, Gurdjieff used every means possible to foster his circle’s financial survival.

“The work went well,” he wrote, “but the excessive pressure of these months, immediately following eight years of uninterrupted labours, fatigued me to such a point that my health was severely shaken, and despite all my desire and effort I could no longer maintain the same intensity.”

Seeking to restore his strength through a dramatic change in setting as well as fundraise for the institute, Gurdjieff devised a plan to tour America with forty-six students. The troupe would put on demonstrations of the sacred dances they practiced and present Gurdjieff’s lectures and ideas to the public. Although intended to attract donors, the ocean voyage and lodgings entailed significant upfront expenses. Last-minute adjustments and unforeseen costs consumed nearly all the teacher’s remaining resources.

“To set out on such a long journey with such a number of people,” he wrote, “and not have any reserve cash for an emergency was, of course, unthinkable.”

The trip itself, so meticulously prepped and planned for, faced collapse. “And then,” Gurdjieff wrote, “as has happened to me more than once in critical moments of my life, there occurred an entirely unexpected event.” He continued:

What occurred was one of those interventions that people who are capable of thinking consciously — in our times and particularly in past epochs — have always considered a sign of the just providence of the Higher Powers. As for me, I would say that it was the law-conformable result of a man’s unflinching perseverance in bringing all his manifestations into accordance with the principles he has consciously set himself in life for the attainment of a definite aim.

As Gurdjieff sat in his room pondering their troubles, his elderly mother entered. She had reached Paris just a few days earlier. His mother was part of the group fleeing Russia but she and others got stranded in the Caucasus. “It was only recently that I had succeeded,” Gurdjieff wrote, “after a great deal of trouble, in getting them to France.”

She handed her son a package, which she told him was a burden from which she desperately wished to be relieved. Gurdjieff opened the package to discover a forgotten brooch of significant value that he had given her back in Eastern Europe. He intended it as a barter item used to pass a border or secure food and shelter. He assumed it was long since sold or otherwise traded and never again thought of it. But there it was. At the precipice of ruin, they were saved.

“I almost jumped up and danced for joy,” he wrote. This was the lawful result of “unflinching perseverance.”

As with all Gurdjieff wrote and said, there is at the back of his statement a level of gravitas and lived experience that makes this teaching warranting of deep pause. Things that might appear homiletic in the mouth of a lesser figure took on life-and-death seriousness from this teacher.

Iclose this brief consideration with a statement of Ouspensky’s. It is not, perhaps, considered one of his most remarkable observations, but it is useful and instructive insofar as it demonstrates how his and Gurdjieff’s ideas cannot be contextualized within familiar categories.

Philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934–2022), a student of the Gurdjieff work, remarked, “It’s not like anything.”

Ouspensky made a valuable observation about the nature of a “positive attitude” in a talk reproduced in the posthumously published book, A Further Record: Extracts from Meetings 1928–1945. In its lowest and least useful iteration, Ouspensky told students,

. . . a positive attitude does not really mean a positive attitude, it simply means liking certain things. A really positive attitude is something quite different. Positive attitude can be defined better than positive emotion, because it refers to thinking. But a real positive attitude includes in itself understanding of the thing itself and understanding of the quality of the thing from the point of view, let us say, of evolution and those things that are obstacles. Things that are against, i.e., if they don’t help, they are not considered, they simply don’t exist, however big they may be externally. And by not seeing them, i.e., if they disappear, one can get rid of their influence. Only, again it is necessary to understand that not seeing wrong things does not mean indifference; it is something quite dif- ferent from indifference.

What the teacher is saying, albeit on a great scale, is that the individual must seek to understand forces that develop or erode his or her humanity, itself an immense question.

We are unconcerned with coordinates of good or bad, happy or sad, but rather with questions of developmental forces and what they mean to us.

This article is adapted from the author’s Modern Occultism (2023):

“Treats esoteric ideas & movements with an even-handed intellectual studiousness”-Washington Post | PEN Award-winning historian | Censored in China

Jul 1, 2023

127,085 views • Jul 1, 2023A documentary on George Gurdjieff with Armenian sub-titles. Contains original and rare footage of the Gurdjieff movements and music from the 1920’s and covers the basis of his teaching in his own words. George Gurdjieff was born in 1867 in Gyumri (formerly Alexandropol) in Armenia. His father Ivan was Greek and his mother Yeva was Armenian. The film was made by Jean-Claude Lubtchansky, a close associate of Madame de Salzmann, with the support of the Gurdjieff Institute in France and is best viewed in full screen on a television or laptop. Osho described Gurdjieff as one of the most significant spiritual masters of this era and indeed this is a film well worth watching. Gurdjieff’s teaching is fully described in the book called “In Search of the Miraculous” which can be read at http://www.gurdjieff.am Your comments are welcome. We live on a wonderful and possibly unique planet in the universe and can only be grateful for every second of life that is granted to us.

(Contributed by Zoë Robinson, H.W., M.)

In the summer of 1947, Ouspensky retires to Lyne Place with a small circle of followers, embarking on a series of excursions to landmarks of significance during his life in England, with the apparent aim to retrace and reconstruct his memory of all of the episodes to which they were connected. Those who join Ouspensky on these trips view it in the air of an expedition which requires that they continually work to string together meaning by his enigmatic clues and hints in order to navigate.

[OUSPENSKY] What is this place?

[MISS P] Lyne Place.

[OUSPENSKY] What is it connected with?

[MISS P] It is connected with everything.

[OUSPENSKY] That’s it – exactly. xiii

By September 4, 1947, much preparation is underway on both sides of the Atlantic for Ouspensky’s return to America, with his people at Lyne Place arranging for his departure while those at Franklyn Farms make ready for his arrival. Yet at the very point of boarding the ship, Ouspensky cancels the whole voyage and requests to return to Lyne Place, a decision that immediately reveals itself to have been his plan all along.

[OUSPENSKY] You know I never intended to go to America – not for a minute.xiii

This sudden reversal of plans makes room for a sequence of extraordinary and strange events in which Ouspensky’s companions accustom themselves to meet with near unconditional acceptance, no matter how unusual the request or unreasonable the demand. He compels the household to break all routines, blurring day with night, continuing the scavenger hunt throughout England as he demonstrates an astonishing command of will over his frail and severely weakened state.

[OUSPENSKY] Do you understand that everything can only be done by effort, or do you think that things can happen right? xiii

[STUDENT] How do I find real “I”?

[OUSPENSKY] By making demands on oneself. I show you the way. xiii

Those among his inner circle account of continual supernatural phenomena taking place amid these last days. They ascribe to Ouspensky the faculty to orchestrate people and events by means of telepathy, how he is able to induce special conditions and scenarios as if directing and producing a theatrical performance with his own conscious death as the central plot, and by which each of his peers, through the part they play, is instructed on the future of their own personal work.

[OUSPENSKY] This is not a dress rehearsal. This is not miracle. This is preparation for preparation for a miracle.xiii

Ouspensky dies on October 2, 1947 in Lyne Place, with those with him at the end left with the steadfast conviction that he continued onwards, in the spirit of his lifelong adherence to the Theory of Recurrence, to find himself returned once again a newborn infant in Moscow on March 5, 1878. The conscious design of this final period serves as a testament to his embodiment of the teaching to which he dedicated his life.

[OUSPENSKY] Think about death. You do not know how much time remains to you. And remember that if you do not become different, everything will be repeated again, all foolish blunders, all silly mistakes, all loss of time and opportunity — everything will be repeated with the exception of the chance you had this time, because chance never comes in the same form.xiv

IN 2022/3, BEPERIOD WILL BE CREATING A FULL-LENGTH DOCUMENTARY ON GEORGE GURDJIEFF

Part I:

Gurdjieff

Part II:

Teaching

Part III:

School

Part IV:

Initiation

Part V:

Fourth Way

(ggurdjieff.com)

When Ouspensky arrives in London in August 1921, he is greeted with the popularity of the English translation of Tertium Organum, which, unknown to him, was published a year earlier in New York and England. Some key members of London’s intellectual circles find his work spellbinding and through their influence and financial support he has a platform to expound Gurdjieff’s teaching.

The final break with Gurdjieff in 1924 marks the point at which Ouspensky resolves to establish his own independent school. But in spite of his access to ample material resources and receptive audiences, he intentionally keeps growth in check during the 1920s, restricting the number of students to be admitted, and focuses much of his time on his publications, often including the London group in the writing process.

[OUSPENSKY] The system is waiting for workers. There is no statement and no thought in it which would not require and admit further development and elaboration. But there are great difficulties in the way of training people for this work, since an ordinary intellectual study of the system is quite insufficient; and there are very few people who agree to other methods of study who are at the same time capable of working by these methods.viii

The 1930s ushers in a new climate of expansion. Ouspensky publishes A New Model of the Universe in 1931, restrictions are removed which allows more students to join the school, and larger properties are secured where they can live and work together. The farm at Lyne Place is purchased in 1935, and Colet Gardens in London in 1938, which prompts the establishment of the school’s outer form, the ‘Historico-Psychological Society’.

The society’s constitution outlines the chief aims of the Ouspensky school:

The study of problems of the evolution of man and particularly of the idea of psycho-transformism.

The study of psychological schools in different historical periods and in different countries, and the study of their influence on the moral and intellectual development of humanity.

Practical investigation of methods of self-study and self-development according to principles and methods of psychological schools.

Research work in the history of religions, of philosophy, of science, and of art with the object of establishing their common origin when it can be found and different psychological levels in each of them.ix

At the same time that a momentum is building in the school with more activities and more ambitious plans – his students now numbering over one thousand – there is also an escalation of the war in Europe, which by 1939 forces Ouspensky to bring all the school’s work to an abrupt halt and make the decision to move to the United States. By 1941, he begins holding meetings in New York, and Franklin Farms, a large house and estate in New Jersey, is acquired the following year to serve as his new home and a teaching center for the students who followed him from England and for the American students he will attract.

To be continued…

IN 2022/3, BEPERIOD WILL BE CREATING A FULL-LENGTH DOCUMENTARY ON GEORGE GURDJIEFF

Part I:

Gurdjieff

Part II:

Teaching

Part III:

School

Part IV:

Initiation

Part V:

Fourth Way

(ggurdjieff.com)

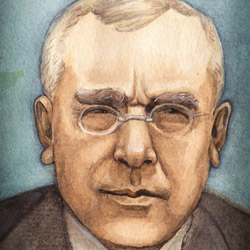

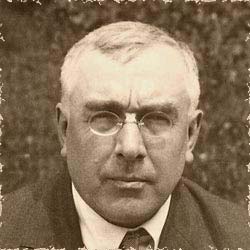

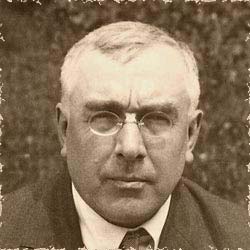

Piotr Demianovich Ouspensky (March 4, 1878–October 2, 1947) was a Russian philosopher who rejected the science and psychology of his time under the strong suspicion that there had to exist superior systems of thought. In his youth, he studied mysticism and esotericism and traveled extensively in search of ancient wisdom, sensing that past ages knew more than his present one. “I felt that there was a dead wall everywhere,” he commented in one of his early biographical notes. “I used to say at that time that professors were killing science in the same way as priests were killing religion.”

When Ouspensky met George Gurdjieff and was introduced to the Fourth Way in 1915, he realized that the barrier towards knowledge lay in oneself; one couldn’t find the truth without simultaneously laboring to live the truth. Real knowledge could only come with sufficient preparation for receiving it. Ouspensky spent the rest of his life laboring to make the Fourth Way principles his own and to share them with like-minded people. In so doing, he became an agent of truth for his age, carrying the wisdom of the pre-World War era into the middle of the twentieth century.

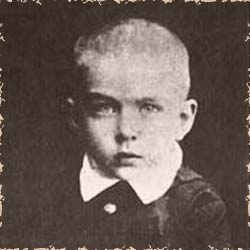

Ouspensky was born in Moscow in 1878 in a middle class household that was fond of the arts. In his autobiographical accounts he describes himself as atypical, a disinterest in behaving like other children, and an early inclination towards more mature topics like the natural sciences. His lucid memory of these very early years extended to even before the age of two:

Peter Ouspensky

[MAURICE NICOLL] But I am sure that you remember your life far better than I remember mine, and that your life has had more meaning.

[OUSPENSKY] Yes, but not quite in the way you mean. I have noticed how much you have forgotten. In my case, as a child I did not play with toys. I was less under imagination. I saw what life was like at a very early stage. i

Maurice Nicoll

These precocious qualities appear to have crystallized in his youth both a steadfast dissatisfaction with the schooling system and, later in his adolescence, an unwavering sense of disapproval towards the academic and scientific establishment. The impulse to take personal ownership of his studies began to be apparent as early as the age six, with Ouspensky choosing to be self-taught in the sciences instead of pursuing formal education, with a particular fascination with the theory of the fourth dimension.

Behind this impulse, however, lay the more indelible mark left on his psyche in repeated experiences of déjà vu between Ouspensky and his younger sister, then five and three years of age, in which he recounts how they were able to remember small events before them having yet occurred.

[OUSPENSKY] How can you speak to mother, grandmother, about former lives even when you learn to talk? They will lock you up. I remembered very well. I was very lonely. I had to wait for sister to be born and then to learn to speak, three, four years perhaps, before I had someone to talk to.

Then it used to happen often like this: she used to look out of window and tell me about people she saw. There was very good combination in our street, policeman first, then postman, like that. She used to know who would come round corner because she remembered.

She would say (only we used our own baby language), “Now there will be policeman.” I say, “And now will come tax collector,” and he came. When we did this often I said to her, “Shall we tell mother, grandmother?” And little sister would say, “What use to tell mother, grandmother? They don’t know, they don’t understand anything.” Just think, I was five, she was three. ii

Ouspensky in Childhood

These experiences undoubtedly contributed to the very early conviction in the young Ouspensky of the existence of a veiled reality behind which stood a much different world with radically different meanings towards life than what was ordinarily understood by the adults around him. It was the inherent seed in him that expressed itself in later years of studies and personal development, and never in fact ceased.

The theory that we live and repeat the same life over and over again represented to the young Ouspensky a living truth, and was inextricably linked and energized by his fascination with higher dimensions. By the age of 27, he wrote a novel titled A Strange Life of Osokin which encapsulated his understanding of the laws governing eternal recurrence and the possibility of change.

Two years later, Ouspensky discovered Theosophy and was introduced to the many branches of esotericism, with entirely new approaches to the pursuit of higher realities. His study of Theosophical literature drew him into psychology, personal experiments, and exotic travels, all of which was conveyed in a series of publications and lectures on topics including the Tarot and Yoga, attracting a considerable audience.

[OUSPENSKY] I discovered the idea of esotericism, found a possible angle for the study of religion and mysticism, and received a new impetus for the study of “higher dimensions”. iii

Ouspensky’s acclaim reached new heights with the publication of Tertium Organum, hailed as a masterpiece in addressing the problem of higher dimensions, and established the now 34 year old as a preeminent philosopher. However, these worldly achievements always appeared to be of secondary interest to him, as the deeper yearning ingrained in his character since childhood made it impossible to settle for the commonplace. Throughout his life, Ouspensky would constantly insist on reaching for nothing short of direct access to the miraculous.

Ouspensky in 1912

Ouspensky’s literary success did not blind him to the fact that experiencing higher dimensions was altogether superior to writing a bestseller on them. He resolved to seek out the miraculous in actual practice, by coming in direct contact with schools that possessed knowledge and practical methods. And so his search continued.

[OUSPENSKY] When I went away I already knew I was going to look for a school or schools. I had arrived at this long ago. I realized that personal, individual efforts were insufficient and that it was necessary to come into touch with the real and living thought which must be in existence somewhere but with which we had lost contact. This I understood; but the idea of schools itself changed very much during my travels and in one way became simpler and more concrete and in another way became more cold and distant. I want to say that schools lost much of their fairy-tale character. iv

From 1913 to 1914, Ouspensky traveled in search of a school, the majority of this time devoted to India, and while he was successful in obtaining a better understanding of the types of schools that existed, he remained no closer to discovering one suitable to his search. He had planned to continue his search in the Middle East when the trip was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War, requiring him to return home.

Soon after his return to a politically-turbulent Russia, Ouspensky organized lectures to share what he had discovered in India with the aim of gathering like-minded people who were interested in his spiritual pursuits. At one such lecture, held in Moscow, he was approached by two of Gurdjieff’s pupils, who informed him of a group engaged in occult investigations and experiments. They invited him to meet their teacher. While Ouspensky had a poor first impression about the prospect and responded with disinterest, he agreed to the meeting after some insistence by one of the pupils.

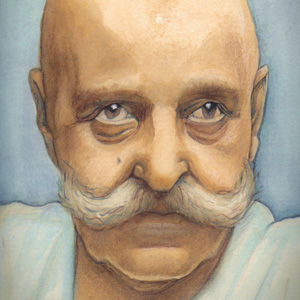

Gurdjieff (1908-1910?)

[OUSPENSKY] In the spring of 1915 I met in Moscow a strange man who had a kind of philosophical school. This was George I. Gurdjieff. He and his ideas produced a very great impression on me. Very soon I realized that he had found many things for which I had been looking in India. I realized that I had met with a completely new system of thought surpassing all I knew before. This system threw quite a new light on psychology and explained what I could not understand before in esoteric ideas and ‘school principles’. iii

[OUSPENSKY] In his explanations I felt the assurance of a specialist, a very fine analysis of facts, and a system which I could not grasp, but the presence of which I already felt because Gurdjieff’s explanations made me think not only of the facts under discussion, but also of many other things I had observed or conjectured. iv

[OUSPENSKY] I saw without hesitation that in the domain [psychology] which I knew better than any other and in which I was really able to distinguish the old from the new, the known from the unknown, Gurdjieff knew more than all European science taken as a whole. v

Gurdjieff and Ouspensky Circa 1915

Ouspensky immediately recognized in Gurdjieff the quality of teacher and school that had eluded him throughout all his personal study and seeking abroad. He soon helped form the early St. Petersburg group that Gurdjieff would regularly travel to from Moscow, and became a member of Gurdjieff’s inner circle for several years, playing a key role in establishing the school from the Russian Revolution up until the formation of the institute at Fontainebleau.

Ouspensky’s recollection of this period has been meticulously documented in his book In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, published posthumously, and widely held to serve as a masterful introduction to the teachings of Gurdjieff.

Ouspensky’s life is forever altered in the summer of 1916 when he finds himself immersed in a week of miracles. Among a small group of Gurdjieff’s closest pupils in a country house in Finland, his inner work intensifies to an inflection point. The combination of personal and group exercises cultivates in him a heightened state of emotional tension, leading up to the shock of engaging in telepathic conversations with Gurdjieff.

[OUSPENSKY] It all started with my beginning to hear his thoughts. We were sitting in a small room with a carpetless wooden floor as it happens in country houses. I sat opposite G., and Dr. S. and Z. at either side. G. spoke of our “features,” of our inability to see or to speak the truth. His words perturbed me very much. And suddenly I noticed that among the words which he was saying to us all there were “thoughts” which were intended for me. I caught one of these thoughts and replied to it, speaking aloud in the ordinary way. G. nodded to me and stopped speaking. There was a fairly long pause. He sat still saying nothing. After a while I heard his voice inside me as it were in the chest near the heart. He put a definite question to me. I looked at him; he was sitting and smiling. His question provoked in me a very strong emotion. But I answered him in the affirmative.iv

It dawns on Ouspensky that this state of unusual tension is the key to all higher perception, and that higher phenomena is impossible to investigate without this strange emotion as the precondition. The subjective yet extraordinary discovery is the answer to his search for the miraculous, contextualizing Gurdjieff’s teaching up until this point as having prepared the ground for it.

[OUSPENSKY] There is something in phenomena of a higher order which requires a particular emotional state for their observation and study. And this excludes any possibility of “properly conducted” laboratory experiments and observations.iv

[OUSPENSKY] This state, which is emotional, is exactly what we do not understand, that is, we do not understand that it is indispensable and that facts are not possible without it.iv

[OUSPENSKY] It is necessary to create a certain particular energy or point (using it in the ordinary sense), and that can be created only at a moment of very serious emotional stress. All the work before that is only preparation of the method.vi

The miracles do not end in Finland but continue for weeks afterwards, in which Ouspensky encounters “sleeping people” traveling past him on the street, a higher perception that he observes lasts as long as he himself does not fall asleep. While these facts of a higher order are of immeasurable value to him, the unusual tension that accompanies the experience is constant and often challenging to endure.

[OUSPENSKY] How can this be got rid of? I cannot bear it any more.

[GURDJIEFF] Do you want to go to sleep?

[OUSPENSKY] Certainly not.

[GURDJIEFF] Then what are you asking about? This is what you wanted, make use of it. You are not asleep at this moment! iv

In the following summer of 1917, Gurdjieff gathers 13 of his students in a small house on the fringes of Essentuki, a city at the base of the Caucasus mountains in Russia. The group undergoes six-weeks of an exhausting program, night and day, that Ouspensky recounts as deeply significant in his understanding of the knowledge and practical methods of Gurdjieff’s teaching.

Then, abruptly, in connection to an incident involving one of his senior students, Gurdjieff announces that the group is disbanded and all work abandoned.

[OUSPENSKY] And suddenly everything changed. For a reason that seemed to me to be accidental and which was the result of friction between certain members of our small group, Gurdjieff announced that he was dispersing the whole group and stopping all work.iv

[OUSPENSKY] All this surprised me very much. I considered the moment most inappropriate for “acting,” and if what Gurdjieff said was serious, then why had the whole business been started? During this period nothing new had appeared in us. And if Gurdjieff had started work with us such as we were, then why was he stopping it now?iv

The degree of shock, confusion, and disappointment naturally have a dramatic effect on the group, but with Ouspensky it also plants a seed of disillusionment towards Gurdjieff, compelling him from that moment to begin drawing a distinction between the teacher and the teaching.

[OUSPENSKY] And I have to confess that my confidence in Gurdjieff began to waver from this moment. What the matter was and what particularly provoked me is difficult for me to define even now. But the fact is that from this moment there began to take place in me a separation between Gurdjieff himself and his ideas. Until then I had not separated them.iv

The rift continues to widen as Ouspensky refuses two invitations to join Gurdjieff in Tiflis in 1919 and participate in the initial debut of his ‘Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man’. Ouspensky is unimpressed by the nature of its establishment.

[OUSPENSKY] Gurdjieff was obviously obliged to give some sort of outward form to his work having regard to outward conditions, [but] I was not very enthusiastic about the program of the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man… whose outward form was somewhat in the nature of a caricature. iv

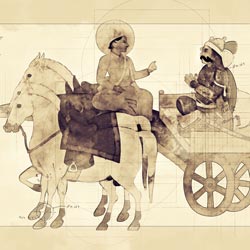

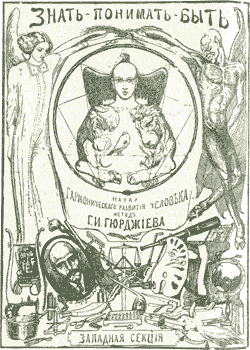

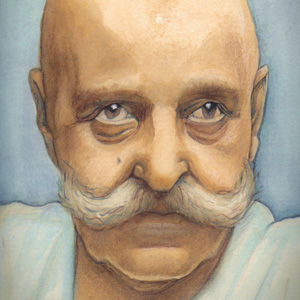

Prospectus of the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man (Circa 1919)

The break is not immediate but gradually marked through a series of events in Constantinople, London, and Paris. Ouspensky repeatedly makes efforts to resume work with his former teacher, only to come back to the same realization of its impossibility. Once Gurdjieff establishes the Château du Prieuré in France, and following his near-fatal car accident in 1924, Ouspensky severs ties with him completely.

[OUSPENSKY] I have asked you to come because I must tell you that I have decided to break off all relations with Mr. Gurdjieff. This means that you have to choose. Either you can go and work with him, or you can work with me: but if you remain with me, you must give an undertaking [understanding] that you will not communicate in any way with Mr. Gurdjieff.vii

[OUSPENSKY] When I met Gurdjieff I began to work with him on the basis of certain principles which I could understand and accept. He said: ‘First of all you must not believe anything, and second you must not do anything you don’t understand.’ I accepted him because of that. Then after two or three years, I saw him going against these principles. He demanded from people to accept what they did not believe and to do what they did not understand. Why this happened I don’t pretend to offer any theory. v

[OUSPENSKY] Question: Has it ever crossed your mind to regret having ever met Gurdjieff?

Ouspensky: Never. Why? I got very much from him. I am always very grateful to myself that after the first evening I asked him when I could see him next time. If I had not, we would not be sitting here now.

Question: But you wrote two very brilliant books.

Ouspensky: They were only books. I wanted more. I wanted something for myself. v

To be continued…

IN 2022/3, BEPERIOD WILL BE CREATING A FULL-LENGTH DOCUMENTARY ON GEORGE GURDJIEFF

Part I:

Gurdjieff

Part II:

Teaching

Part III:

School

Part IV:

Initiation

Part V:

Fourth Way

(ggurdjieff.com)

New Thinking Sep 1, 2023 This video is a special release from the original Thinking Allowed series that ran on public television from 1986 until 2002. It was recorded in about 1988. The average human is functioning in an unawakened state, according to Russian philosopher and mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. Psychologist Kathleen Speeth, Ph.D., author of The Gurdjieff Work and Gurdjieff: Seeker of the Truth, was raised by parents who were students of Gurdjieff, whom she met as a child. She discusses the history and present status of the Gurdjieff movement and the fundamental exercise of “remembering oneself.” Now you can watch all of the programs from the original Thinking Allowed Video Collection, hosted by Jeffrey Mishlove. Subscribe to the new Streaming Channel (https://thinkingallowed.vhx.tv/) and watch more than 350 programs now, with more, previously unreleased titles added weekly. Free month of the classic Thinking Allowed streaming channel for New Thinking Allowed subscribers only. Use code THINKFREELY.

Piotr Demianovich Ouspensky (March 4, 1878–October 2, 1947) was a Russian philosopher who rejected the science and psychology of his time under the strong suspicion that there had to exist superior systems of thought. In his youth, he studied mysticism and esotericism and traveled extensively in search of ancient wisdom, sensing that past ages knew more than his present one. “I felt that there was a dead wall everywhere,” he commented in one of his early biographical notes. “I used to say at that time that professors were killing science in the same way as priests were killing religion.”

When Ouspensky met George Gurdjieff and was introduced to the Fourth Way in 1915, he realized that the barrier towards knowledge lay in oneself; one couldn’t find the truth without simultaneously laboring to live the truth. Real knowledge could only come with sufficient preparation for receiving it. Ouspensky spent the rest of his life laboring to make the Fourth Way principles his own and to share them with like-minded people. In so doing, he became an agent of truth for his age, carrying the wisdom of the pre-World War era into the middle of the twentieth century.

Ouspensky was born in Moscow in 1878 in a middle class household that was fond of the arts. In his autobiographical accounts he describes himself as atypical, a disinterest in behaving like other children, and an early inclination towards more mature topics like the natural sciences. His lucid memory of these very early years extended to even before the age of two:

Peter Ouspensky

[MAURICE NICOLL] But I am sure that you remember your life far better than I remember mine, and that your life has had more meaning.

[OUSPENSKY] Yes, but not quite in the way you mean. I have noticed how much you have forgotten. In my case, as a child I did not play with toys. I was less under imagination. I saw what life was like at a very early stage. i

Maurice Nicoll

These precocious qualities appear to have crystallized in his youth both a steadfast dissatisfaction with the schooling system and, later in his adolescence, an unwavering sense of disapproval towards the academic and scientific establishment. The impulse to take personal ownership of his studies began to be apparent as early as the age six, with Ouspensky choosing to be self-taught in the sciences instead of pursuing formal education, with a particular fascination with the theory of the fourth dimension.

Behind this impulse, however, lay the more indelible mark left on his psyche in repeated experiences of déjà vu between Ouspensky and his younger sister, then five and three years of age, in which he recounts how they were able to remember small events before them having yet occurred.

[OUSPENSKY] How can you speak to mother, grandmother, about former lives even when you learn to talk? They will lock you up. I remembered very well. I was very lonely. I had to wait for sister to be born and then to learn to speak, three, four years perhaps, before I had someone to talk to.

Then it used to happen often like this: she used to look out of window and tell me about people she saw. There was very good combination in our street, policeman first, then postman, like that. She used to know who would come round corner because she remembered.

She would say (only we used our own baby language), “Now there will be policeman.” I say, “And now will come tax collector,” and he came. When we did this often I said to her, “Shall we tell mother, grandmother?” And little sister would say, “What use to tell mother, grandmother? They don’t know, they don’t understand anything.” Just think, I was five, she was three. ii

Ouspensky in Childhood

These experiences undoubtedly contributed to the very early conviction in the young Ouspensky of the existence of a veiled reality behind which stood a much different world with radically different meanings towards life than what was ordinarily understood by the adults around him. It was the inherent seed in him that expressed itself in later years of studies and personal development, and never in fact ceased.

The theory that we live and repeat the same life over and over again represented to the young Ouspensky a living truth, and was inextricably linked and energized by his fascination with higher dimensions. By the age of 27, he wrote a novel titled A Strange Life of Osokin which encapsulated his understanding of the laws governing eternal recurrence and the possibility of change.

Two years later, Ouspensky discovered Theosophy and was introduced to the many branches of esotericism, with entirely new approaches to the pursuit of higher realities. His study of Theosophical literature drew him into psychology, personal experiments, and exotic travels, all of which was conveyed in a series of publications and lectures on topics including the Tarot and Yoga, attracting a considerable audience.

[OUSPENSKY] I discovered the idea of esotericism, found a possible angle for the study of religion and mysticism, and received a new impetus for the study of “higher dimensions”. iii

Ouspensky’s acclaim reached new heights with the publication of Tertium Organum, hailed as a masterpiece in addressing the problem of higher dimensions, and established the now 34 year old as a preeminent philosopher. However, these worldly achievements always appeared to be of secondary interest to him, as the deeper yearning ingrained in his character since childhood made it impossible to settle for the commonplace. Throughout his life, Ouspensky would constantly insist on reaching for nothing short of direct access to the miraculous.

Ouspensky in 1912

Ouspensky’s literary success did not blind him to the fact that experiencing higher dimensions was altogether superior to writing a bestseller on them. He resolved to seek out the miraculous in actual practice, by coming in direct contact with schools that possessed knowledge and practical methods. And so his search continued.

[OUSPENSKY] When I went away I already knew I was going to look for a school or schools. I had arrived at this long ago. I realized that personal, individual efforts were insufficient and that it was necessary to come into touch with the real and living thought which must be in existence somewhere but with which we had lost contact. This I understood; but the idea of schools itself changed very much during my travels and in one way became simpler and more concrete and in another way became more cold and distant. I want to say that schools lost much of their fairy-tale character. iv

From 1913 to 1914, Ouspensky traveled in search of a school, the majority of this time devoted to India, and while he was successful in obtaining a better understanding of the types of schools that existed, he remained no closer to discovering one suitable to his search. He had planned to continue his search in the Middle East when the trip was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War, requiring him to return home.

Soon after his return to a politically-turbulent Russia, Ouspensky organized lectures to share what he had discovered in India with the aim of gathering like-minded people who were interested in his spiritual pursuits. At one such lecture, held in Moscow, he was approached by two of Gurdjieff’s pupils, who informed him of a group engaged in occult investigations and experiments. They invited him to meet their teacher. While Ouspensky had a poor first impression about the prospect and responded with disinterest, he agreed to the meeting after some insistence by one of the pupils.

Gurdjieff (1908-1910?)

[OUSPENSKY] In the spring of 1915 I met in Moscow a strange man who had a kind of philosophical school. This was George I. Gurdjieff. He and his ideas produced a very great impression on me. Very soon I realized that he had found many things for which I had been looking in India. I realized that I had met with a completely new system of thought surpassing all I knew before. This system threw quite a new light on psychology and explained what I could not understand before in esoteric ideas and ‘school principles’. iii

[OUSPENSKY] In his explanations I felt the assurance of a specialist, a very fine analysis of facts, and a system which I could not grasp, but the presence of which I already felt because Gurdjieff’s explanations made me think not only of the facts under discussion, but also of many other things I had observed or conjectured. iv

[OUSPENSKY] I saw without hesitation that in the domain [psychology] which I knew better than any other and in which I was really able to distinguish the old from the new, the known from the unknown, Gurdjieff knew more than all European science taken as a whole. v

Gurdjieff and Ouspensky Circa 1915

Ouspensky immediately recognized in Gurdjieff the quality of teacher and school that had eluded him throughout all his personal study and seeking abroad. He soon helped form the early St. Petersburg group that Gurdjieff would regularly travel to from Moscow, and became a member of Gurdjieff’s inner circle for several years, playing a key role in establishing the school from the Russian Revolution up until the formation of the institute at Fontainebleau.

Ouspensky’s recollection of this period has been meticulously documented in his book In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, published posthumously, and widely held to serve as a masterful introduction to the teachings of Gurdjieff.

To be continued…

(ggurdjieff.com)