From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Chief Joseph | |

|---|---|

| Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it | |

| Chief Joseph in 1877 | |

| Born | March 3, 1840 Wallowa Valley, Nez Perce territory (claimed as Oregon Country by the United States and as the Columbia District by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) |

| Died | September 21, 1904 (aged 64) Colville Indian Reservation, Washington, United States |

| Resting place | Chief Joseph Cemetery Nespelem, Washington  48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″WCoordinates: 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″WCoordinates:  48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W |

| Other names | In-mut-too-yah-lat-latChief JosephJoseph the YoungerYoung Joseph |

| Known for | Nez Perce leader |

| Predecessor | Joseph the Elder (father) |

| Spouses | Heyoon YoyiktSpringtime |

| Children | Jean-Louise |

| Parents | Tuekakas (father)Khapkhaponimi (mother) |

| Relatives | Sousouquee (older brother), Ollokot (younger brother), four sisters |

| Signature | |

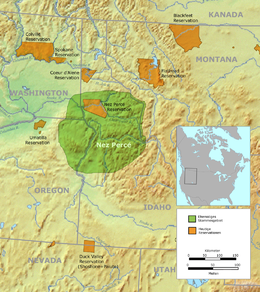

Original Nez Perce territory (green) and the reduced reservation of 1863 (brown)

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt (or Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe of the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States, in the latter half of the 19th century. He succeeded his father Tuekakas (Chief Joseph the Elder) in the early 1870s.

Chief Joseph led his band of Nez Perce during the most tumultuous period in their history, when they were forcibly removed by the United States federal government from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley of northeastern Oregon onto a significantly reduced reservation in the Idaho Territory. A series of violent encounters with white settlers in the spring of 1877 culminated in those Nez Perce who resisted removal, including Joseph’s band and an allied band of the Palouse tribe, to flee the United States in an attempt to reach political asylum alongside the Lakota people, who had sought refuge in Canada under the leadership of Sitting Bull.

At least 700 men, women, and children led by Joseph and other Nez Perce chiefs were pursued by the U.S. Army under General Oliver O. Howard in a 1,170-mile (1,900 km) fighting retreat known as the Nez Perce War. The skill with which the Nez Perce fought and the manner in which they conducted themselves in the face of incredible adversity earned them widespread admiration from their military opponents and the American public, and coverage of the war in U.S. newspapers led to popular recognition of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce.

In October 1877, after months of fugitive resistance, most of the surviving remnants of Joseph’s band were cornered in northern Montana Territory, just 40 miles (64 km) from the Canadian border. Unable to fight any longer, Chief Joseph surrendered to the Army with the understanding that he and his people would be allowed to return to the reservation in western Idaho. He was instead transported between various forts and reservations on the southern Great Plains before being moved to the Colville Indian Reservation in the state of Washington, where he died in 1904.

Chief Joseph’s life remains an iconic event in the history of the American Indian Wars. For his passionate, principled resistance to his tribe’s forced removal, Joseph became renowned as both a humanitarian and a peacemaker.

Background

Chief Joseph was born Hinmuuttu-yalatlat (alternatively Hinmaton-Yalaktit or Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt [Nez Perce: “Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain”], or Hinmatóoyalahtq’it [“Thunder traveling to higher areas”])[1] in the Wallowa Valley of northeastern Oregon. He was known as Young Joseph during his youth because his father, Tuekakas,[2] was baptized with the same Christian name and later become known as “Old Joseph” or “Joseph the Elder”.[3]

While initially hospitable to the region’s white settlers, Joseph the Elder grew wary when they demanded more Indian lands. Tensions grew as the settlers appropriated traditional Indian lands for farming and livestock. Isaac Stevens, governor of the Washington Territory, organized a council to designate separate areas for natives and settlers in 1855. Joseph the Elder and the other Nez Perce chiefs signed the Treaty of Walla Walla,[4] with the United States establishing a Nez Perce reservation encompassing 7,700,000 acres (31,000 km2) in present-day Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. The 1855 reservation maintained much of the traditional Nez Perce lands, including Joseph’s Wallowa Valley.[5] It is recorded that the elder Joseph requested that Young Joseph protect their 7.7-million-acre homeland, and guard his father’s burial place.[6]

In 1863, however, an influx of new settlers, attracted by a gold rush, led the government to call a second council. Government commissioners asked the Nez Perce to accept a new, much smaller reservation of 760,000 acres (3,100 km2) situated around the village of Lapwai in western Idaho Territory, and excluding the Wallowa Valley.[7][8] In exchange, they were promised financial rewards, schools, and a hospital for the reservation. Chief Lawyer and one of his allied chiefs signed the treaty on behalf of the Nez Perce Nation, but Joseph the Elder and several other chiefs were opposed to selling their lands and did not sign.[9][10][11][12]

Their refusal to sign caused a rift between the “non-treaty” and “treaty” bands of Nez Perce. The “treaty” Nez Perce moved within the new reservation’s boundaries, while the “non-treaty” Nez Perce remained on their ancestral lands. Joseph the Elder demarcated Wallowa land with a series of poles, proclaiming, “Inside this boundary all our people were born. It circles the graves of our fathers, and we will never give up these graves to any man.”

Leadership of the Nez Perce

Joseph the Younger succeeded his father as leader of the Wallowa band in 1871. Before his death, the latter counseled his son:

“My son, my body is returning to my mother earth, and my spirit is going very soon to see the Great Spirit Chief. When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never sold his country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. A few years more and white men will be all around you. They have their eyes on this land. My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.”[13]

Joseph commented: “I clasped my father’s hand and promised to do as he asked. A man who would not defend his father’s grave is worse than a wild beast.”

The non-treaty Nez Perce suffered many injustices at the hands of settlers and prospectors, but out of fear of reprisal from the militarily superior Americans, Joseph never allowed any violence against them, instead making many concessions to them in the hope of securing peace. A handwritten document mentioned in the Oral History of the Grande Ronde recounts an 1872 experience by Oregon pioneer Henry Young and two friends in search of acreage at Prairie Creek, east of Wallowa Lake. Young’s party was surrounded by 40–50 Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph. The Chief told Young that white men were not welcome near Prairie Creek, and Young’s party was forced to leave without violence.[14]

An 1889 photograph of Joseph speaking to ethnologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher and her interpreter James Stuart

In 1873, Joseph negotiated with the federal government to ensure his people could stay on their land in the Wallowa Valley. But in 1877, the government reversed its policy, and Army General Oliver O. Howard threatened to attack if the Wallowa band did not relocate to the Idaho reservation with the other Nez Perce. Joseph reluctantly agreed. Before the outbreak of hostilities, General Howard held a council at Fort Lapwai to try to convince Joseph and his people to relocate. Joseph finished his address to the general, which focused on human equality, by expressing his “[disbelief that] the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do.” Howard reacted angrily, interpreting the statement as a challenge to his authority. When Toohoolhoolzote protested, he was jailed for five days.

The day following the council, Joseph, White Bird, and Looking Glass all accompanied Howard to examine different areas within the reservation. Howard offered them a plot of land that was inhabited by whites and Native Americans, promising to clear out the current residents. Joseph and his chieftains refused, adhering to their tribal tradition of not taking what did not belong to them. Unable to find any suitable uninhabited land on the reservation, Howard informed Joseph that his people had 30 days to collect their livestock and move to the reservation. Joseph pleaded for more time, but Howard told him he would consider their presence in the Wallowa Valley beyond the 30-day mark an act of war.

Returning home, Joseph called a council among his people. At the council, he spoke on behalf of peace, preferring to abandon his father’s grave over war. Toohoolhoolzote, insulted by his incarceration, advocated war. In June 1877, the Wallowa band began making preparations for the long journey to the reservation, meeting first with other bands at Rocky Canyon. At this council, too, many leaders urged war, while Joseph continued to argue in favor of peace. While the council was underway, a young man whose father had been killed rode up and announced that he and several other young men had retaliated by killing four white settlers. Still hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Joseph and other non-treaty Nez Perce leaders began moving people away from Idaho.