Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.

1 John 4:7-21 (KJV)

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.

1 John 4:7-21 (KJV)

Published in Original Philosophy

3 days ago (Medium.com)

Karl Marx published Das Kapital in 1867, almost eight years after the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. Both were momentous in changing our way of thinking about relationships, particularly that between society and science. But more importantly, they got us thinking about what relationship nature has to science. While both authors were similarly interested in how the social could be extracted from the scientific, they each had their personal trajectory when it came to analyzing how the science figured in the social, and vice-versa. But the focus in this story will be on Marx and the parallels between his thinking about scientific knowledge and that of the natural scientists making up his contemporaries.

The mid-nineteenth century also saw increased divergence between the biological and physical sciences, probably because physics was becoming more of a mathematically-abstract investigation into nature while biology remained largely concerned with describing nature as they could be humanly observed, even if instrumental extensions, such as the microscope and field glasses, were used. Even when the physicists and biologists worked together, it was still about adapting physical models to biological issues rather than vice-versa. And these physical and mathematical models would become foundational to the materialist philosophical discourse on science and technology, without reducing the discourse to pure models.

Marx was eager to ensure that his work would have scientifically solid foundations, and he dived into mathematics, economics, and the physical sciences to give his work a more rigorous padding [1]. The correspondences between Engels and Marx demonstrated their continuous interest in keeping abreast of developments in the different disciplines of the natural sciences from the mid to late nineteenth century. They desired to comprehend the relationship between ‘scientific’ developments and the idealist philosophy of nature that was dominant during their time. Their areas of interests included examining the physical forces at work in nature and how quantification operated in heat, electricity, and magnetism [2].

In his 1856 speech delivered at the anniversary celebration of the People’s Paper, Marx made metaphorical references to geological features while declaring that the revolution of a social nature was ephemeral and incapable of holding a candle to technological revolution. He warned that ignorance over the interactions between scientific discovery and society, and the subsequent deployment of science without awareness to serve the desire of capital, could lead to the enslavement of humans.

That social revolution, it is true, was no novelty invented in 1848. Steam, electricity, and the self-acting mule were revolutionists of a rather more dangerous character than even citizens Barbés, Raspail and Blanqui… On the one hand, there have started into life industrial and scientific forces, which no epoch of the former human history had ever suspected. On the other hand, there exist symptoms of decay, far surpassing the horrors recorded of the latter times of the Roman Empire. [3]

The critique on physics and metaphysics that Engels and Marx had engaged in were increasingly reified with the rise of logical positivism, starting from the late nineteenth to the first half of the twentieth century, specifically in Vienna, Cambridge, London, and later, North America. It was a historical irony that some of the important scholars in the philosophy of science during the early twentieth century were concerned with differentiating the perceived affectations of metaphysics from the natural sciences. On the other hand, physicists, including the pioneers of quantum physics, were less concerned about separating their ideological beliefs from their scientific work. Indeed, there were conflicts in how the pioneers of quantum mechanics saw as extensions to interpretations in the new physics they pioneered — many were not against contemplating the philosophical and political implications of their work [4].

While Marx and his fellow philosophers (and sociologists) were raising consciousness around the superstructures of capitalism, value, and (asset) accumulation, the pioneers of modern science were busy reconciling the theorization of ‘atoms’ (electricity) with paradoxes observed in the thermodynamics of heat. One of the latter, Lord Kelvin, had thought that the atomic spectra might have a role to play in making time more precise because of the observable discrete behaviors of the atoms[5]. Time became a valuable commodity from the time it had been used to plot the financial graphs of loss and profits as embodied by the Stock Exchange. The increasing complexity of stock manipulation and the financial markets made the need for greater precision in measuring time inevitable.

Time as the subject of measurement became pre-eminent in philosopher Antonio Negri’s analyses of productivity, circulation, and collectivity under capital, in his book Time for Revolution. In fact, the notion that time could have an evolutionary role to play came about when Galilean/Newtonian physics, with its arbitrary constitution of time, had to be revised against the idea that the position, direction, and momentum of a static and dynamic object in relation to each other could make time less fixed but not necessarily more fluid, especially with the onset of the theory of relativity.

Through the emergence of quantum time, driven by the interpretation of atomic wave properties against its discrete values, we are able to re-conceptualize the operation of time at the intersection of what is visible to our world and that which exists at the subatomic scale. Each scale of visibility is represented by the different dimensions of attention in classical physics (with the center of reference being our world of direct experience) and quantum physics (whose conceptualization is non-intuitive and mediated by hidden actors).

It is not coincidental that the rise of scientific knowledge as we know it, after breaking ranks with natural philosophy, occurred at the coming-of-age of the industrial revolution in Europe and the industrialization of North America as well as Japan, as the latter third was also an actor in the construction of scientific modernity during the 19th century. After all, the time for industrial revolution represented the formalization of techno-scientific labor, as that labor moved from the artisanship of the cottage industry to the specifications of machine-driven productivity.

Development in engineering and the applied natural sciences led the more observant and curious of the practitioners, who were not necessarily university-trained, to formulate principles and laws to account for their observations. The players of the new sciences were educated men with footholds in the various scientific academies and royal societies of their countries, as well as autodidacts who apprenticed themselves to other men of science, such as in the case of Humphrey Davy and Michael Faraday.

In the nineteenth century, it was still possible to be an amateur scientist without the academic credentials greasing today’s scientific enterprise, as long as one could find ways of attaining sufficient intellectual capital to enable one’s scientific paper to be accepted and given the stamp of approval by the national academies of science. Of course, an imbalance of power was still at play, in that the learned members of the elite class would still act as gatekeepers. Such attitudes shaped the development of the kind of science Negri refers to as bourgeoisie science — a science that is not about dispelling superstition and terror, but generative of its own collective arbitrary pronouncements in contending with the presuppositions of science as legitimate knowledge[6]. Nevertheless, scientific knowledge was still able to disseminate rapidly not just among the elite circles, but also to members of the public[7].

It is still important to keep in mind the probable fallacies and contradictions that can emerge when we consider how science’s modernizing imperative went hand-in-hand with aggressive imperial expansionism. Most of the colonial men of science had been condescending towards the indigenous knowledges they came into contact [8]. For the colonized, access to the scientific knowledge of the colonizers became the tools for claiming emancipation and nation-building.

The elite class of the group might adopt an attitude of condescension toward knowledge heritage perceived as pseudo-scientific without questioning the rationale, or intellectual conditioning, underlying their attitudes. However, the colonized ‘proleteriats’ were still able to resist at some level.

Take for instance the case of India and her staunch claim regarding the pre-eminence of her intellectual traditions in mathematics and the physical sciences. Even if that heritage knowledge bore little resemblance to modern science, India was not discouraged. Marxism, having contributed ideologically to India’s independence movement, not without some resistance from some of the agitators for India’s independence [9], had also become a big part India’s humanistic scholarship, as Indian scholars became major contributors to postcolonial theories. They also contributed immensely to thinking about postcolonial science and technology that are crucial to the critique of scientific imperialism and commoditization.

The revolution in publishing is a revolution in capitalism and a form of socialistic subversion where knowledge was pried from the firm grip of the bourgeoisie. The rise of mass publishing parallels today’s impetus for open access scientific publishing, as did particular sentiments with regard to the nature of knowledge and the importance of its availability to the public.

The rise of mass publication (such as the penny presses) was supposed to democratize knowledge and encourage social mobility. For the first time, scientific treatises and popular science writings that were considered too much of a luxury even by the rising middle class were now within reach of most of the literate class except the poorest. Readers could read political tracts in tandem with the science books, and writers had been known to dissect them in equal measure.

Among the most active popularizers of the new sciences were women, who were writing mainly to a female market. However, some also wrote to other men less knowledgeable than themselves and to children.[10] After all, women had been involved, as invisible actors, in the scientific enterprise for some centuries. While they were known to publish erudite papers and even books, regardless of whether they had the opportunity for formal advanced education, writing popular science allowed the women to expand their reach and a chance at earning an income in a way that their other intellectual endeavors did not provide.

However, most of the women with any chance of involvement in disseminating scientific knowledge were from the upper to upper-middle classes, and were born into educated (and scientific-minded) families. The intellectual mobility that the democratization of knowledge was supposed to accord was not as available to women except during extenuating circumstances, such as in the absence of men and labor shortage during the war years [11].

Values internal to science and the social world that surrounds science are not exclusive to each other, either now or in the past. Politics were important to scientists of the past when it comes to justifying their theories and interpretations of experimental outcomes. Since the time of Marx, the critical reception of science has undergone several levels of development — we see the rise and fall of social constructivism (the idea that scientific knowledge is socially constructed as knowledge communities develop their own ways of knowing)[12] and relativism (that science is determined by cultural standards that are neither stable nor absolute — it overlaps with social constructivism) [13].

How do the politics of the left (together with the politics from across the spectrum) come together and negotiate policy and ethics in science? Karen Barad, a theoretical physicist and professor of feminist studies, had produced an example of such an intervention happening at the intersection of politics (specifically leftist politics), social justice movement, and theoretical physics through her work [14]. Even then, her work has been met with mixed reception, with some seeing her as a messiah for opening up the materiality of abstract science for interface with politics while others regarded her project as problematic with too many assumptions that are obscured by a dense sea of tangled critical theory.

At the end of the day, it is up to the rest of us who want to push the boundaries of the possible in science and critique of/in science to see how we can produce more pragmatic interventions through our knowledge of history without being held a prisoner of science and its difficult history. It is also up to us to discover if the Marxist materialist politics of science has anything to offer in the age of technoeconomic incursions where policies around the support of scientific production are overshadowed by the economic imperative underpinning the drive toward increased productivity via technologization.

·Writer for Original Philosophy

I write about theory, philosophy, artscience, speculations, technoscience, cultural strategies, and media industries. I may also write on personal development.

5 days ago (grantpiperwriting.medium.com)

There are millions of Christians in the world today whose entire worldview revolves around the idea of heaven and hell. Christians go to heaven. Non-believers go to hell. Therefore, it is the duty of the believer to convert non-believers to save them from hell. Fear of hell is used to keep members in line and to drive people to fervent evangelicalism. Everything is about getting into heaven and avoiding going to the bad place. However, these beliefs do not appear anywhere in the Bible. In fact, an unhealthy obsession with the afterlife is rotting Christianity from the inside out.

If heaven were so important to Jesus, you would think he would have spent most of his time preaching about it. But he didn’t. In fact, Jesus says little about heaven at all. Most of Jesus’s teachings are about the nature and intention of the law, how to treat other people, how to see people the way God sees them, and how to pray and grow near to God — in this life. All of Jesus’s teachings are about how people should act in their physical lives and not about how to get to heaven.

Jesus’s belief in heaven was not at all what people think today. In Judaism, the body and soul are inextricably linked. One cannot live without the other. In order for the soul to reach immortality, the body also has to reach immortality. That is why Jesus’s body is raised from the dead and why there is still a belief that Christians’ bodies will be raised at the end of time.

The idea that the soul is severed from the body and hidden away in heaven is a new idea and one that invalidates large swaths of the same Bible that heaven adherents claim to believe in. Believing that the supernatural realm is more important than the physical realm is contradictory to what the Bible actually says. In fact, the dichotomy between the Bible’s focus on the physical and Christian emphasis on the metaphysical gave rise to Gnosticism. Because at the end of the day, obsessing over heaven and making your life’s work about the afterlife runs counter to what God actually says and actually wants from us.

Focusing on heaven as the final goal of our physical lives is a slap to God’s face. God created the physical world, and he created it for a reason. Genesis says that God created everything, and he said that it was good. All of it was good.

God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. And there was evening, and there was morning — the sixth day. — Genesis 1:31

This lays out some very basic truths that most people gloss over. God made the physical world, and he likes the physical world. Otherwise, why make it? Why focus so much of his time and attention on it? Not only did God create the physical world, but he put man into it. He created man in his own image, breathed his breath of life into him, and set him above his physical creation. So clearly, there is a plan, a purpose, and a love for the physical world. Saying things like “I’m living for heaven” or “this is just a temporary stop before I get to heaven” completely passes over the value that God puts on our physical world.

If the physical world is completely worthless, God would have put no worth on it. But we don’t see any evidence of that. God gives numerous commands about how to treat our bodies, how to eat, and how to treat one another in a physical sense. Sex is physical. Marriage is physical. Eating is physical. Violence is physical. The Bible speaks volumes (literally) about these types of things. If these things mattered not and heaven was the only thing that mattered, then the Bible would speak volumes about heaven and the spiritual realm. Instead, the inverse is true. The Bible speaks little about the spiritual realm and speaks volumes about the physical realm.

The focus on heaven by supposed Christians flummoxed the Gnostics in early Christianity. Gnostics said that if God’s true design for humanity was metaphysical or spiritual, the physical world doesn’t make sense. And in a way, they were right. If God only cares about our souls, why stuff our souls into failable bodies and cause us pain if heaven is the true goal? To resolve this contradiction, the Gnostics claimed that the physical world was created by a pretender god who had basically stolen the worship of the real God who was hidden in the spiritual world. This is why Gnostics believed that Jesus was never physical, only spiritual, and why Gnostics said that “secret knowledge” of the spiritual world was the only way to sidestep the entrapment of the physical world.

Orthodox Christianity crushed Gnosticism without truly dealing with the contradiction that created the heresy in the first place. They put far too much emphasis on heaven. The truth is that heaven does not appear much in the Bible at all.

If we all go to heaven when we die, why would we want to be resurrected back into physical bodies? The resurrection of the body doesn’t make sense if the soul immediately goes to heaven upon death. Who would sign up to leave heaven? Only Jesus did, and it was a burden. If we are already in heaven when we die, why come back to face judgment in the end? It doesn’t make sense.

The Old Testament speaks very little about the idea of heaven. The word for heaven in ancient Hebrew is שמים or shamayim. This word refers to the skies and the stars and is often used in conjunction with the word for land. In this context, the word is used to describe all of God’s physical dominion (the skies and the land.) A derivative of this word can also be used to describe the place where God lives when his presence is not on Earth. God dwells in heaven, but it is not a place that the Jews believed that they could enter. The words “heaven” and “heavens” appear numerous times in the Old Testament but never describe where human souls go after they die.

Again, Jews believed that the soul must reside in the body, which is why the resurrection of the body is such an important part of Jewish and early Christian literature.

Many people like to point to the story in the Old Testament where the prophet Elijah is “taken up into heaven,” but this context only says that Elijah was brought up into the sky. Many believed that Elijah was simply moved to another place. They even went out and looked for him, and a letter from Elijah to a wicked king is recorded as having been written years after he was supposedly taken up into heaven. Elijah never went to the heavenly realms because they are not places that humans can go.

Bible Answers writes on this topic, saying:

As these passages show, a careful reading of the Scriptures shows that Elijah’s miraculous removal in a fiery chariot involved transporting him to another location in the area, not to eternal life in heaven.

Without this story, heaven is completely absent from the Old Testament. The same Old Testament Jesus taught and the same Old Testament that supposedly shows the original revelation of God. If God had nothing to say about heaven over multiple centuries and generations, why should we believe that it is an important cornerstone of our religion today?

Jesus is the founder and perfector of the Christian faith. If heaven was such an important part of his plan, he would have spoken extensively on it. Instead, like the prophets before him, Jesus speaks little to none about heaven. Jesus speaks extensively about the Kingdom of God, but that kingdom is an earthly one. It is here. It is now. Living as followers of Jesus with hearts actively seeking God is the kingdom of heaven.

Jesus spells out exactly what eternal life is, and it is not heaven.

Now this is eternal life: that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent. — John 17:3

Jesus also says:

Then he said to them all: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me.” — Luke 9:23

People must take up their cross daily in this life and follow Jesus now — not in heaven. Jesus was focused on the physical world, just as the Father is. Why ask people to take up their cross daily in this life if heaven is the real goal? If heaven is the real goal, people should only have to pick up their cross once like Jesus did. And indeed, many Christians erroneously believe that you only have to say something or do something once to be saved. But that isn’t what Jesus teaches. Jesus teaches us that following him and seeking God is a constant endeavor.

Jesus taught that there would be a final judgment in which the righteous would be allowed to dwell with God, and the unrighteous would be destroyed. Those with hearts for God, who accept the invitation, will be allowed to live in their resurrected bodies. The rest will face annihilation. (Not hell. Annihilation is being sent to oblivion, apart from God forever.)

Paul teaches the same thing.

Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven. I tell you this, brothers: flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable. Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. — 1 Corinthians 15:49–52

Paul says that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God. The dead will rise to live with God, but that is not quite the same idea that most Christians hold of heaven.

Hebrews says the same thing:

Just as people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment. — Hebrews 9:27

Humans die, then they sleep, and then, at the end, we will all be raised to face judgment. Jesus Christ, the perfect savior and sacrifice, will intercede on behalf of those who followed Him. The rest will stand on their own. The unrighteous will be sorted and perish, and the righteous will live on in new bodies.

Jesus says no one has ascended into heaven. No one.

No one has ever gone into heaven except the one who came from heaven — the Son of Man. Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him. — John 3:13–15

Only Jesus has been to heaven. He is the only human who has experienced heaven. Jesus says that eternal life is in him and that knowing him is eternal life. Ironically, these verses immediately precede the verse that everyone knows by heart, John 3:16, but few people can recite John 3:13–15.

There are entire sects of Christianity devoted to the “sinner’s prayer.” The sinner’s prayer is a belief that a person can simply utter a few words in a moment of passion and suddenly be saved for all eternity. People who utter the sinner’s prayer are saved from hell, and they will go to heaven when they die. That is not what Christianity is about because Christianity is not about going to heaven. Christianity is about following Jesus with the goal of knowing God in this life. God wants to dwell with humanity in this creation, and sin prevents us from growing close to God. Jesus can remove the sin blocking us from God’s presence. In this life.

David and Jesus are held up as great examples of those that God loves. Both of them actively sought God and worked hard to find him in this life. Neither of them was obsessed with heaven, dying, or the afterlife. They were focused on finding God and seeking after him in their physical bodies. Jesus and David both wanted to dwell with God, know God, love God, and follow God. That is what we should strive to emulate.

Christianity is not about heaven. It has never been about heaven. It is not about saving an arbitrary number of souls to live in heaven. Making it about heaven cheapens the religion and simplifies a complex and ancient set of beliefs. The Bible is not focused on heaven, so why are we?

The only thing that would prevent this brand of heaven-centric Christianity from becoming a death cult is the belief that suicide is a sin. (Suicide is a sin because it unlawfully damages God’s physical creation. It is a violent act against a body that God created.) Without that barrier, what would prevent everyone from simply offing themselves to get to God?

Christianity is about following Jesus. Following Jesus allows us to grow close to God. God wants to grow close to us in this life. At the end of the age, God will resurrect everyone’s bodies, and those who have grown near him will be allowed to dwell with him, but not in the way that everyone thinks. Those people who get to dwell with God are the ones who are already dwelling with God in the present physical world (or are striving to). Heaven, in this context is a continuation of the ideal state of being, not a new state of being.

Everyone else will be destroyed and are thus denied access to God. But these people have already set themselves against God in this life and thus will continue to be denied access to God.

The idea that souls will go to heaven when you die and live eternally is a fabrication that switches focus from God to heaven. God wants us to know him in this life. Knowing God is eternal life. The privilege of knowing God is what we should all be striving for. The kingdom of God is here, and now it is not someplace far away that we can only go to when we die.

The modern idea of heaven invalidates much of the Bible. Why focus on the physical if heaven is the goal? Why would God torture us in a physical life if it ultimately doesn’t matter? Why is physical sin such a big deal if God can eliminate it all in heaven? Why did God send his son into the physical world if the physical world doesn’t matter?

The truth is that the idea of following Jesus in this life isn’t all that popular. Heaven is popular. The idea that humans can get an eternal reward for very little actual work on Earth is a tantalizing fabrication. Telling people that following Jesus allows us to get a glimpse of God the Father in this life is the ultimate reward, but it is not as enticing as promising them heaven.

Would it not be the most devious thing to twist God’s teachings to frame it about a fictional heaven in order to turn people away from God’s actual teaching and purpose?

Professional writer. Amateur historian. Husband, father, Christian.

The Majority Report w/ Sam Seder • Premiered 10 hours ago • MR Live Podcast Episodes Happy Martin Luther King Day! MR’s compilation of MLK-related audio returns! Excerpts include: -A previously unheard speech from MLK on reparations, white economic anxiety and guaranteed income -Dr. King’s first TV “interview” from the show “The Open Mind – The New Negro” in 1957, hosted by Professor Richard D. Hefner. -“Beyond Vietnam”, the speech delivered on April 4, 1967 at Riverside Church in New York City. -MLK’s last speech, “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution“, delivered at the National Cathedral, Washington, D.C., on 31 March 1968. -Walter Cronkite reporting King’s assassination in 1968. -Nina Simone performing the song “Why?” live, 3 days following MLK’s assassination at the Westbury Music Fair on Long Island in April 1968.

Coursing through every civilization are the myths that shape what its people come to believe about reality and possibility. Some of them are healing and some damaging. Some are easy to recognize for what they are — almost all isms are damaging myths. But some are more subtle, more pernicious, permeating the substratum of culture and the marrow of the psyche.

One of Western culture’s most damaging myths, largely inherited from the Romantics, is that of the tortured genius — the suffering artist who needs to have suffered and must go on suffering in order to create works of beauty and poignancy, portals to the sacred. The truth, of course, is far more nuanced — artists are simply people who feel life deeply in all of its dimensions, who are awake and alive to both its tragedy and its transcendence, who put their heightened sensitivity in the service of wakefulness and aliveness for others.

Virginia Woolf knew this when she wrote of the shock-receiving capacity necessary for being an artist. In his diary, Walt Whitman contemplated the superior porousness of the creative spirit to both life’s “sunny expanses and sky-reaching heights” and its “bare spots and darknesses,” believing that “no artist or work of the very first class may be or can be without them.”

These, of course, are the polarities we all live with, the polarities that live in us, which Maya Angelou channeled in her stunning poem “A Brave and Startling Truth.” The artist is humanity’s magnifying lens for the inherent dualities of human nature — something James Baldwin captured in his insistence that an artist’s role is “to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.” The measure of our creative vitality lies in how intimately we contact both the doom and the glory of being, what we make of the restless tension between our own poles, how we harmonize them into something beautiful.

Hermann Hesse

In the interlude between two world wars, as humanity hungered for beauty to controvert its own brutality, Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877–August 9, 1962) considered the inner life of the creative spirit in a poignant passage from his 1927 novel Steppenwolf (public library), painting the artist as a divided creature that yearns for wholeness and turns that yearning into the creative act:

Many artists… have two souls, two beings within them. There is God and the devil in them; the mother’s blood and the father’s; the capacity for happiness and the capacity for suffering; and in just such a state of enmity and entanglement towards and within each other as were the wolf and man.

For Hesse’s artist, riven by these inner tensions, “life has no repose.” And yet out of that restlessness comes the artist’s gift to the world:

[Artists] live at times in their rare moments of happiness with such strength and indescribable beauty, the spray of their moment’s happiness is flung so high and dazzlingly over the wide sea of suffering, that the light of it, spreading its radiance, touches others too with its enchantment. Thus, like a precious, fleeting foam over the sea of suffering arise all those works of art, in which a single individual lifts himself for an hour so high above his personal destiny that his happiness shines like a star and appears to all who see it as something eternal and as a happiness of their own.

Complement with other excellent reflections on what it means to be an artist from e.e. cummings, M.C. Richards, Egon Schiele, and Marina Abramović, then revisit Hesse on the courage to be yourself, the wisdom of the inner voice, and how to be more alive.

“The body provides something for the spirit to look after and use,” computing pioneer Alan Turing wrote as he contemplated the binary code of body and spirit in the spring of his twenty-first year, having just lost the love of his life to tuberculosis. Nothing garbles that code more violently than illness — from the temporary terrors of food poisoning to the existential tumult of a terminal diagnosis — our entire mental and emotional being is hijacked by the demands of a malcontented body as dis-ease, in the most literal sense, fills sinew and spirit alike. These rude reminders of our atomic fragility are perhaps the most discomfiting yet most common human experience — it is difficult, if at all possible, to find a person unaffected by illness, for we have all been or will be ill, and have all loved or will love someone afflicted by illness.

No one has articulated the peculiar vexations of illness, nor addressed the psychic transcendence accessible amid the terrors of the body, more thoughtfully than Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) in her 1926 essay “On Being Ill,” later included in the indispensable posthumous collection of her Selected Essays (public library).

Portrait of Virginia Woolf from Literary Witches.

Half a century before Susan Sontag’s landmark book Illness as Metaphor, Woolf writes:

Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness, how we go down into the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers when we have a tooth out and come to the surface in the dentist’s arm-chair and confuse his “Rinse the mouth — rinse the mouth” with the greeting of the Deity stooping from the floor of Heaven to welcome us — when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. Novels, one would have thought, would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia; lyrics to toothache. But no; with a few exceptions — De Quincey attempted something of the sort in The Opium Eater; there must be a volume or two about disease scattered through the pages of Proust — literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear, and, save for one or two passions such as desire and greed, is null, and negligible and non-existent.

Five years earlier, the ailing Rilke had written in a letter to a young woman: “I am not one of those who neglect the body in order to make of it a sacrificial offering for the soul, since my soul would thoroughly dislike being served in such a fashion.” Woolf, writing in the year of Rilke’s death and well ahead of the modern scientific inquiry into how the life of the body shapes the life of the mind, rebels against the residual Cartesianism of the mind-body divide with her characteristic fusion of wisdom and wry humor, channeled in exquisite prose:

All day, all night the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February. The creature within can only gaze through the pane — smudged or rosy; it cannot separate off from the body like the sheath of a knife or the pod of a pea for a single instant; it must go through the whole unending procession of changes, heat and cold, comfort and discomfort, hunger and satisfaction, health and illness, until there comes the inevitable catastrophe; the body smashes itself to smithereens, and the soul (it is said) escapes. But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record. People write always of the doings of the mind; the thoughts that come to it; its noble plans; how the mind has civilised the universe. They show it ignoring the body in the philosopher’s turret; or kicking the body, like an old leather football, across leagues of snow and desert in the pursuit of conquest or discovery. Those great wars which the body wages with the mind a slave to it, in the solitude of the bedroom against the assault of fever or the oncome of melancholia, are neglected. Nor is the reason far to seek. To look these things squarely in the face would need the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth. Short of these, this monster, the body, this miracle, its pain, will soon make us taper into mysticism, or rise, with rapid beats of the wings, into the raptures of transcendentalism.

Art from the vintage science primer The Human Body: What It Is and How It Works.

“Is language the adequate expression of all realities?” Nietzsche had asked when Woolf was just genetic potential in her parents’ DNA. Language, the fully formed human argues as she considers the unreality of illness, has been utterly inadequate in conferring upon this commonest experience the dignity of representation it confers upon just about every other universal human experience:

To hinder the description of illness in literature, there is the poverty of the language. English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache. It has all grown one way.

In a passage Oliver Sacks could have written, Woolf pivots to the humorous, somehow without losing the profundity of the larger point:

Yet it is not only a new language that we need, more primitive, more sensual, more obscene, but a new hierarchy of the passions; love must be deposed in favour of a temperature of 104; jealousy give place to the pangs of sciatica; sleeplessness play the part of villain, and the hero become a white liquid with a sweet taste — that mighty Prince with the moths’ eyes and the feathered feet, one of whose names is Chloral.

And then, just like that, in classic Woolfian fashion, she fangs into the meat of the matter — the way we plunge into the universality of illness, so universal as to border on the banal, until we reach the rock bottom of utter existential aloneness:

That illusion of a world so shaped that it echoes every groan, of human beings so tied together by common needs and fears that a twitch at one wrist jerks another, where however strange your experience other people have had it too, where however far you travel in your own mind someone has been there before you — is all an illusion. We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others. Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest in each; a snowfield where even the print of birds’ feet is unknown. Here we go alone, and like it better so. Always to have sympathy, always to be accompanied, always to be understood would be intolerable.

Art by Nina Cosford from the illustrated biography of Virginia Woolf

In health, Woolf argues, we maintain the illusion, both psychological and outwardly performative, of being cradled in the arms of civilization and society. Illness jolts us out of it, orphans us from belonging. But it also does something else, something beautiful and transcendent: In piercing the trance of busyness and obligation, it awakens us to the world about us, whose smallest details, neglected by our regular societal conscience, suddenly throb with aliveness and magnetic curiosity. It renders us “able, perhaps for the first time for years, to look round, to look up — to look, for example, at the sky”:

The first impression of that extraordinary spectacle is strangely overcoming. Ordinarily to look at the sky for any length of time is impossible. Pedestrians would be impeded and disconcerted by a public sky-gazer. What snatches we get of it are mutilated by chimneys and churches, serve as a background for man, signify wet weather or fine, daub windows gold, and, filling in the branches, complete the pathos of dishevelled autumnal plane trees in autumnal squares. Now, lying recumbent, staring straight up, the sky is discovered to be something so different from this that really it is a little shocking. This then has been going on all the time without our knowing it! — this incessant making up of shapes and casting them down, this buffeting of clouds together, and drawing vast trains of ships and waggons from North to South, this incessant ringing up and down of curtains of light and shade, this interminable experiment with gold shafts and blue shadows, with veiling the sun and unveiling it, with making rock ramparts and wafting them away…

But in the consolations of this transcendent communion with nature resides the most disquieting fact of existence — the awareness of an unfeeling universe, operating by impartial laws unconcerned with our individual fates:

Divinely beautiful it is also divinely heartless. Immeasurable resources are used for some purpose which has nothing to do with human pleasure or human profit.

Drawing from The Comet Book — a 16th-century pre-astronomical document of magical thinking about the laws of the universe.

It would take Woolf more than a decade to fully formulate, in a most stunning reflection, the paradoxical way in which these heartless laws are the very reason we are called to make beauty and meaning within their unfeeling parameters: “There is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself,” she would write in 1939. Now, in her meditation on illness, she hones the anchor of these ideas:

Poets have found religion in nature; people live in the country to learn virtue from plants. It is in their indifference that they are comforting. That snowfield of the mind, where man has not trodden, is visited by the cloud, kissed by the falling petal, as, in another sphere, it is the great artists, the Miltons and the Popes, who console not by their thought of us but by their forgetfulness.

[…]

It is only the recumbent who know what, after all, Nature is at no pains to conceal — that she in the end will conquer; heat will leave the world; stiff with frost we shall cease to drag ourselves about the fields; ice will lie thick upon factory and engine; the sun will go out.

This sudden awareness of elemental truth renders the ill person a sort of seer, imbued with an almost mystical understanding of existence, beyond any intellectual interpretation. Nearly a century before Patti Smith came to contemplate how illness expands the field of poetic awareness, Woolf writes:

In illness words seem to possess a mystic quality. We grasp what is beyond their surface meaning, gather instinctively this, that, and the other — a sound, a colour, here a stress, there a pause — which the poet, knowing words to be meagre in comparison with ideas, has strewn about his page to evoke, when collected, a state of mind which neither words can express nor the reason explain. Incomprehensibility has an enormous power over us in illness, more legitimately perhaps than the upright will allow. In health meaning has encroached upon sound. Our intelligence domineers over our senses. But in illness, with the police off duty, we creep beneath some obscure poem by Mallarmé or Donne, some phrase in Latin or Greek, and the words give out their scent and distil their flavour, and then, if at last we grasp the meaning, it is all the richer for having come to us sensually first, by way of the palate and the nostrils, like some queer odour.

Complement this portion of Woolf’s thoroughly fantastic Selected Essays with Roald Dahl on how illness emboldens creativity and Alice James — Henry and William James’s brilliant sister, whom Woolf greatly admired — on how to live fully while dying, then revisit Woolf on the art of letters, the relationship between loneliness and creativity, the creative potency of the androgynous mind, and her transcendent account of a total solar eclipse.

“Pay attention. It’s all about paying attention. It’s all about taking in as much of what’s out there as you can, and not letting the excuses and the dreariness of some of the obligations you’ll soon be incurring narrow your lives. Attention is vitality. It connects you with others. It makes you eager. Stay eager.”

–SUSAN SONTAG

Susan Lee Sontag (January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) was an American writer, critic, and public intellectual. She mostly wrote essays, but also published novels; she published her first major work, the essay “Notes on ‘Camp’ “, in 1964. Wikipedia

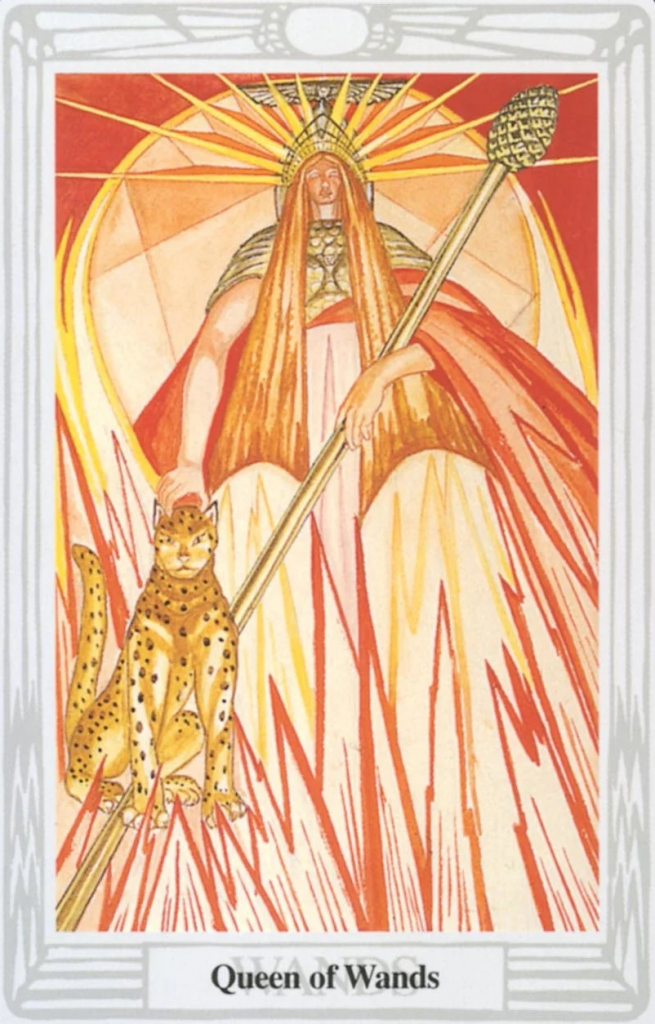

| The Queen of Wands As a suit, Wands are direct, determined and connected to Will and its appropriate application. The Queen of Wands represents a woman who knows exactly what she wants out of life, and aims at her goals with great dedication.She is often a woman who has experienced conflict and trauma, and learned from these. She’s usually independent, forthright and self-motivated. As a friend she will be loyal and honest, though sometimes given to handing out unwelcome advice, and taking over.As a parent she can be quite dominant, claiming that she wants her off spring to be self-reliant and confident, but sometimes tending to become impatient, and do things on their behalf in her own way, rather than allowing her children to make up their own minds.She’s a fighter, who does not suffer fools gladly. She will support and assist those who are vulnerable and needy, offering unceasing energy and determination. She takes up causes readily, and proves herself a worthy adversary. However she has a tendency not to know when to stop, and enjoys being at the forefront of the battle, rather than beavering away on the more routine aspects of any campaign.This is a forceful and proud woman. She applies high standards to everything she becomes involved in. As a result, she can sometimes be somewhat intolerant of people who do things differently.So – The Queen of Wands – a fine ally, and a dangerous enemy! |

Coordinates:  40°10′51″N 76°10′57″W

40°10′51″N 76°10′57″W

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Ephrata.

| Ephrata, PennsylvaniaEffridaa(Pennsylvania German) | |

|---|---|

| Borough | |

| Main Street during the Ephrata Fair | |

| Etymology: Ephrath | |

| Location of Ephrata in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania | |

Coordinates:  40°10′51″N 76°10′57″W 40°10′51″N 76°10′57″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Lancaster |

| Incorporated | August 22, 1891 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ralph Mowen |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 3.46 sq mi (8.97 km2) |

| • Land | 3.42 sq mi (8.85 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.11 km2) |

| Elevation | 358 ft (109 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 13,794 |

| • Density | 4,035.69/sq mi (1,558.18/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 17522 |

| Area codes | 717 |

| Website | ephrataboro.org |

Ephrata (/ˈɛfrətə/ EF-rə-tə; Pennsylvania German: Effridaa) is a borough in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located 42 miles (68 km) east of Harrisburg and about 60 miles (97 km) west-northwest of Philadelphia and is named after Ephrath, the former name for current-day Bethlehem.[3] In its early history, Ephrata was a pleasure resort and an agricultural community.

Ephrata’s population has steadily grown over the last century. In 1900, 2,452 people lived there, and by 1940, the population had increased to 6,199. The population was 13,818 at the 2020 census.[4] Ephrata is the most populous borough in Lancaster County.

Ephrata’s sister city is Eberbach, Germany, the city where its founders originated.

Ephrata is noteworthy for having been the former seat of the Mystic Order of the Solitary, a semimonastic order of Seventh-Day Dunkers. The community, which contained both men and women, was founded by Johann Conrad Beissel in 1732.

Many of the members were well-educated; Peter Miller, second prior of the monastery, translated the Declaration of Independence into seven languages, at the request of Congress. At the period of its greatest prosperity, the community contained nearly 300 persons.[5][6]

The Ephrata Commercial Historic District, Ephrata Cloister, Eby Shoe Corporation buildings, Connell Mansion, Mentzer Building, and Mountain Springs Hotel are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[7]

Ephrata is located in northeastern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania at 40°10′51″N 76°10′57″W (40.17870, −76.17744).[8] U.S. Route 322 passes through the center of the borough as Main Street; it leads northwest 28 miles (45 km) to Hershey and southeast 35 miles (56 km) to West Chester. Pennsylvania Route 272 passes through the northwest side of Ephrata, leading northeast 8 miles (13 km) to Adamstown and southwest 13 miles (21 km) to Lancaster, the county seat. Like the rest of the county, the surrounding land is mostly flat and suitable for farming.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the borough has a total area of 3.4 square miles (8.8 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2), or 1.27%, are water.[9] Cocalico Creek flows through the borough just north of the center of town; it is a southwest-flowing tributary of the Conestoga River and part of the Susquehanna River watershed.

Ephrata has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa), and average monthly temperatures range from 30.0 °F (−1.1 °C) in January to 74.6 °F (23.7 °C) in July.[10] The hardiness zone is 6b.

More at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ephrata,_Pennsylvania

“We think we can play with love, but we are mistaken. Love plays with us. It is far more powerful than we are, and if at first we seem to be fitting love into our lives, this is only love’s way of smiling at us as we are drawn under its thrall. Lightly, ecstatically, we cross the bridge that love lays down for us. And soon enough we are fighting for our lives.”

–Jacob Needleman from The Wisdom of Love

Jacob Needleman (October 6, 1934 – November 28, 2022) was an American philosopher, author, and religious scholar. Needleman was Jewish and was educated at Harvard University, Yale University, and the University of Freiburg, Germany. He was deeply involved in the Gurdjieff Work and the Gurdjieff Foundation of San Francisco. Wikipedia