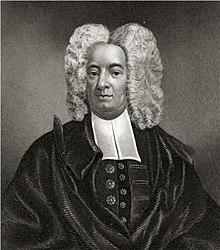

Cotton Mather, FRS (February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728; A.B. 1678, Harvard College; A.M. 1681, honorary doctorate 1710, University of Glasgow) was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author, and pamphleteer. He left a scientific legacy due to his hybridization experiments and his promotion of inoculation for disease prevention, though he is most frequently remembered today for his vigorous support for the Salem witch trials. He was subsequently denied the presidency of Harvard College which his father, Increase Mather, had held.

Life and work

Mather was born in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, the son of Maria (née Cotton) and Increase Mather, and grandson of both John Cottonand Richard Mather, all also prominent Puritan ministers. Mather was named after his maternal grandfather John Cotton. He attended Boston Latin School, where his name was posthumously added to its Hall of Fame, and graduated from Harvard in 1678 at age 15. After completing his post-graduate work, he joined his father as assistant pastor of Boston’s original North Church (not to be confused with the Anglican/Episcopal Old North Church of Paul Revere fame). In 1685, Mather assumed full responsibilities as pastor of the church.[1]:8

Mather lived on Hanover Street, Boston, 1688–1718[2]

Mather wrote more than 450 books and pamphlets, and his ubiquitous literary works made him one of the most influential religious leaders in America. He set the moral tone in the colonies, and sounded the call for second- and third-generation Puritans to return to the theological roots of Puritanism, whose parents had left England for the New England colonies of North America. The most important of these was Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) which comprises seven distinct books, many of which depict biographical and historical narratives.[citation needed]

The Mather tomb in Copp’s Hill Cemetery

Mather was not known for writing in a neutral, unbiased perspective. Many, if not all, of his writings had bits and pieces of his own personal life in them or were written for personal reasons. According to literary historian Sacvan Bercovitch:[3]

Few puritans more loudly decried the bosom serpent of egotism than did Cotton Mather; none more clearly exemplified it. Explicitly or implicitly, he projects himself everywhere in his writings. In the most direct compensatory sense, he does so by using literature as a means of personal redress. He tells us that he composed his discussions of the family to bless his own, his essays on the riches of Christ to repay his benefactors, his tracts on morality to convert his enemies, his funeral discourses to console himself for the loss of a child, wife, or friend.

Mather influenced early American science. In 1716, he conducted one of the first recorded experiments with plant hybridizationbecause of observations of corn varieties. This observation was memorialized in a letter to his friend James Petiver:[4]

First: my Friend planted a Row of Indian corn that was Coloured Red and Blue; the rest of the Field being planted with corn of the yellow, which is the most usual color. To the Windward side, this Red and Blue Row, so infected Three or Four whole Rows, as to communicate the same Colour unto them; and part of ye Fifth and some of ye Sixth. But to the Leeward Side, no less than Seven or Eight Rows, had ye same Colour communicated unto them; and some small Impressions were made on those that were yet further off.[5]

In November 1713, Mather’s wife, newborn twins, and two-year-old daughter all succumbed during a measles epidemic.[6] He was twice widowed, and only two of his 15 children survived him; he died on the day after his 65th birthday and was buried on Copp’s Hill, near Old North Church.[1]: