From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

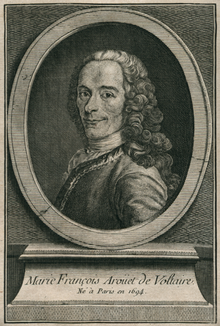

| Voltaire | |

|---|---|

| Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière, c. 1720s | |

| Born | François-Marie Arouet 21 November 1694 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 30 May 1778 (aged 83) Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris, France |

| Occupation | Writer, philosopher |

| Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Collège Louis-le-Grand |

| Partner | Émilie du Châtelet (1733–1749), Marie Louise Mignot (1744–1778) |

| Philosophy career | |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy French philosophy |

| School | Lumières Philosophes Deism Classical liberalism |

| Main interests | Political philosophy, literature, historiography, biblical criticism |

| Notable ideas | Philosophy of history,[1] freedom of religion, freedom of speech, separation of church and state |

| showInfluences | |

| showInfluenced | |

| Signature | |

François-Marie Arouet (French: [fʁɑ̃swa maʁi aʁwɛ]; 21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his nom de plume M. de Voltaire (/vɒlˈtɛər, voʊl-/;[5][6][7] also US: /vɔːl-/;[8][9] French: [vɔltɛːʁ]), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—especially of the Roman Catholic Church—and of slavery. Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

Voltaire was a versatile and prolific writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, histories, and scientific expositions. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and 2,000 books and pamphlets.[10] Voltaire was one of the first authors to become renowned and commercially successful internationally. He was an outspoken advocate of civil liberties and was at constant risk from the strict censorship laws of the Catholic French monarchy. His polemics witheringly satirized intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day. His best-known work and magnum opus, Candide, is a novella which comments on, criticizes, and ridicules many events, thinkers, and philosophies of his time.

Early life

François-Marie Arouet was born in Paris, the youngest of the five children of François Arouet (1649–1722), a lawyer who was a minor treasury official, and his wife, Marie Marguerite Daumard (c. 1660–1701), whose family was on the lowest rank of the French nobility.[11] Some speculation surrounds Voltaire’s date of birth, because he claimed he was born on 20 February 1694 as the illegitimate son of a nobleman, Guérin de Rochebrune or Roquebrune.[12] Two of his older brothers—Armand-François and Robert—died in infancy, and his surviving brother Armand and sister Marguerite-Catherine were nine and seven years older, respectively.[13] Nicknamed “Zozo” by his family, Voltaire was baptized on 22 November 1694, with François de Castagnère, abbé de Châteauneuf [fr], and Marie Daumard, the wife of his mother’s cousin, standing as godparents.[14] He was educated by the Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704–1711), where he was taught Latin, theology, and rhetoric;[15] later in life he became fluent in Italian, Spanish, and English.[16]

By the time he left school, Voltaire had decided he wanted to be a writer, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to become a lawyer.[17] Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a notary, spent much of his time writing poetry. When his father found out, he sent Voltaire to study law, this time in Caen, Normandy. But the young man continued to write, producing essays and historical studies. Voltaire’s wit made him popular among some of the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. In 1713, his father obtained a job for him as a secretary to the new French ambassador in the Netherlands, the marquis de Châteauneuf [fr], the brother of Voltaire’s godfather.[18] At The Hague, Voltaire fell in love with a French Protestant refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer (known as ‘Pimpette’).[18] Their affair, considered scandalous, was discovered by de Châteauneuf and Voltaire was forced to return to France by the end of the year.[19]

Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille from 16 May 1717 to 15 April 1718 in a windowless cell with ten-foot-thick walls.[20]

Most of Voltaire’s early life revolved around Paris. From early on, Voltaire had trouble with the authorities for critiques of the government. As a result, he was twice sentenced to prison and once to temporary exile to England. One satirical verse, in which Voltaire accused the Régent of incest with his daughter, resulted in an eleven-month imprisonment in the Bastille.[21] The Comédie-Française had agreed in January 1717 to stage his debut play, Œdipe, and it opened in mid-November 1718, seven months after his release.[22] Its immediate critical and financial success established his reputation.[23] Both the Régent and King George I of Great Britain presented Voltaire with medals as a mark of their appreciation.[24]

He mainly argued for religious tolerance and freedom of thought. He campaigned to eradicate priestly and aristo-monarchical authority, and supported a constitutional monarchy that protects people’s rights.[25][26]

Arouet adopted the name Voltaire in 1718, following his incarceration at the Bastille. Its origin is unclear. It is an anagram of AROVET LI, the Latinized spelling of his surname, Arouet, and the initial letters of le jeune (“the young”).[27] According to a family tradition among the descendants of his sister, he was known as le petit volontaire (“determined little thing”) as a child, and he resurrected a variant of the name in his adult life.[28] The name also reverses the syllables of Airvault, his family’s home town in the Poitou region.[29]

Richard Holmes[30] supports the anagrammatic derivation of the name, but adds that a writer such as Voltaire would have intended it to also convey connotations of speed and daring. These come from associations with words such as voltige (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), volte-face (a spinning about to face one’s enemies), and volatile (originally, any winged creature). “Arouet” was not a noble name fit for his growing reputation, especially given that name’s resonance with à rouer (“to be beaten up”) and roué (a débauché).

In a letter to Jean-Baptiste Rousseau in March 1719, Voltaire concludes by asking that, if Rousseau wishes to send him a return letter, he do so by addressing it to Monsieur de Voltaire. A postscript explains: “J’ai été si malheureux sous le nom d’Arouet que j’en ai pris un autre surtout pour n’être plus confondu avec le poète Roi“, (“I was so unhappy under the name of Arouet that I have taken another, primarily so as to cease to be confused with the poet Roi.”)[31] This probably refers to Adenes le Roi, and the ‘oi’ diphthong was then pronounced like modern ‘ouai’, so the similarity to ‘Arouet’ is clear, and thus, it could well have been part of his rationale. Voltaire is known also to have used at least 178 separate pen names during his lifetime.[32]

Career

Early fiction

Voltaire’s next play, Artémire, set in ancient Macedonia, opened on 15 February 1720. It was a flop and only fragments of the text survive.[33] He instead turned to an epic poem about Henry IV of France that he had begun in early 1717.[34] Denied a licence to publish, in August 1722 Voltaire headed north to find a publisher outside France. On the journey, he was accompanied by his mistress, Marie-Marguerite de Rupelmonde, a young widow.[35]

At Brussels, Voltaire and Rousseau met up for a few days, before Voltaire and his mistress continued northwards. A publisher was eventually secured in The Hague.[36] In the Netherlands, Voltaire was struck and impressed by the openness and tolerance of Dutch society.[37] On his return to France, he secured a second publisher in Rouen, who agreed to publish La Henriade clandestinely.[38] After Voltaire’s recovery from a month-long smallpox infection in November 1723, the first copies were smuggled into Paris and distributed.[39] While the poem was an instant success, Voltaire’s new play, Mariamne, was a failure when it first opened in March 1724.[40] Heavily reworked, it opened at the Comédie-Française in April 1725 to a much-improved reception.[40] It was among the entertainments provided at the wedding of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska in September 1725.[40]

Great Britain

In early 1726, the aristocratic chevalier de Rohan-Chabot taunted Voltaire about his change of name, and Voltaire retorted that his name would win the esteem of the world, while Rohan would sully his own.[41] The furious Rohan arranged for his thugs to beat up Voltaire a few days later.[42] Seeking redress, Voltaire challenged Rohan to a duel, but the powerful Rohan family arranged for Voltaire to be arrested and imprisoned without trial in the Bastille on 17 April 1726.[43][44] Fearing indefinite imprisonment, Voltaire asked to be exiled to England as an alternative punishment, which the French authorities accepted.[45] On 2 May, he was escorted from the Bastille to Calais and embarked for Britain.[46]

Elémens de la philosophie de Neuton, 1738

In England, Voltaire lived largely in Wandsworth, with acquaintances including Everard Fawkener.[47] From December 1727 to June 1728 he lodged at Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, now commemorated by a plaque, to be nearer to his British publisher.[48] Voltaire circulated throughout English high society, meeting Alexander Pope, John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and many other members of the nobility and royalty.[49] Voltaire’s exile in Great Britain greatly influenced his thinking. He was intrigued by Britain’s constitutional monarchy in contrast to French absolutism, and by the country’s greater freedom of speech and religion.[50] He was influenced by the writers of the time, and developed an interest in English literature, especially Shakespeare, who was still little known in continental Europe.[51] Despite pointing out Shakespeare’s deviations from neoclassical standards, Voltaire saw him as an example for French drama, which, though more polished, lacked on-stage action. Later, however, as Shakespeare’s influence began growing in France, Voltaire tried to set a contrary example with his own plays, decrying what he considered Shakespeare’s barbarities. Voltaire may have been present at the funeral of Isaac Newton,[a] and met Newton’s niece, Catherine Conduitt.[48] In 1727, he published two essays in English, Upon the Civil Wars of France, Extracted from Curious Manuscripts and Upon Epic Poetry of the European Nations, from Homer Down to Milton.[48] Voltaire also published a letter about the Quakers after he attended one of their services.[52]

After two and a half years in exile, Voltaire returned to France, and after a few months in Dieppe, the authorities permitted him to return to Paris.[53] At a dinner, French mathematician Charles Marie de La Condamine proposed buying up the lottery that was organized by the French government to pay off its debts, and Voltaire joined the consortium, earning perhaps a million livres.[54] He invested the money cleverly and on this basis managed to convince the Court of Finances of his responsible conduct, allowing him to take control of a trust fund inherited from his father. He was now indisputably rich.[55][56]

Further success followed in 1732 with his play Zaïre, which when published in 1733 carried a dedication to Fawkener praising English liberty and commerce.[57] He published his admiring essays on British government, literature, religion, and science in Letters Concerning the English Nation (London, 1733).[58] In 1734, they were published in Rouen as Lettres philosophiques, causing a huge scandal.[59][b] Published without approval of the royal censor, the essays lauded British constitutional monarchy as more developed and more respectful of human rights than its French counterpart, particularly regarding religious tolerance. The book was publicly burnt and banned, and Voltaire was again forced to flee Paris.[25]

Château de Cirey

In the frontispiece to Voltaire’s book on Newton’s philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire’s muse, reflecting Newton’s heavenly insights down to Voltaire.[60]

In 1733, Voltaire met Émilie du Châtelet (Marquise du Châtelet), a mathematician and married mother of three, who was 12 years his junior and with whom he was to have an affair for 16 years.[61] To avoid arrest after the publication of Lettres, Voltaire took refuge at her husband’s château at Cirey on the borders of Champagne and Lorraine.[62] Voltaire paid for the building’s renovation,[63] and Émilie’s husband sometimes stayed at the château with his wife and her lover.[64] The intellectual paramours collected around 21,000 books, an enormous number for the time.[65] Together, they studied these books and performed scientific experiments at Cirey, including an attempt to determine the nature of fire.[66]

Having learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began his habit of avoiding open confrontation with the authorities and denying any awkward responsibility.[67] He continued to write plays, such as Mérope (or La Mérope française) and began his long researches into science and history. Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire were the years of his British exile, during which he had been strongly influenced by the works of Isaac Newton. Voltaire strongly believed in Newton’s theories; he performed experiments in optics at Cirey,[68] and was one of the promulgators of the famous story of Newton’s inspiration from the falling apple, which he had learned from Newton’s niece in London and first mentioned in his Letters.[48]

Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1735

In the fall of 1735, Voltaire was visited by Francesco Algarotti, who was preparing a book about Newton in Italian.[69] Partly inspired by the visit, the Marquise translated Newton’s Latin Principia into French, which remained the definitive French version into the 21st century.[25] Both she and Voltaire were also curious about the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary and rival of Newton. While Voltaire remained a firm Newtonian, the Marquise adopted certain aspects of Leibniz’s critiques.[25][70] Voltaire’s own book Elements of the Philosophy of Newton made the great scientist accessible to a far greater public, and the Marquise wrote a celebratory review in the Journal des savants.[25][71] Voltaire’s work was instrumental in bringing about general acceptance of Newton’s optical and gravitational theories in France, in contrast to the theories of Descartes.[25][72]

Voltaire and the Marquise also studied history, particularly the great contributors to civilization. Voltaire’s second essay in English had been “Essay upon the Civil Wars in France”. It was followed by La Henriade, an epic poem on the French King Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, which established religious toleration. There followed a historical novel on King Charles XII of Sweden. These, along with his Letters on the English, mark the beginning of Voltaire’s open criticism of intolerance and established religions.[citation needed] Voltaire and the Marquise also explored philosophy, particularly metaphysical questions concerning the existence of God and the soul. Voltaire and the Marquise analyzed the Bible and concluded that much of its content was dubious.[73] Voltaire’s critical views on religion led to his belief in separation of church and state and religious freedom, ideas that he had formed after his stay in England.

In August 1736, Frederick the Great, then Crown Prince of Prussia and a great admirer of Voltaire, initiated a correspondence with him.[74] That December, Voltaire moved to Holland for two months and became acquainted with the scientists Herman Boerhaave and Willem ‘s Gravesande.[75] From mid-1739 to mid-1740 Voltaire lived largely in Brussels, at first with the Marquise, who was unsuccessfully attempting to pursue a 60-year-old family legal case regarding the ownership of two estates in Limburg.[76] In July 1740, he traveled to the Hague on behalf of Frederick in an attempt to dissuade a dubious publisher, van Duren, from printing without permission Frederick’s Anti-Machiavel.[77] In September Voltaire and Frederick (now King) met for the first time in Moyland Castle near Cleves and in November Voltaire was Frederick’s guest in Berlin for two weeks,[78] followed by a meeting in September 1742 at Aix-la-Chapelle.[79] Voltaire was sent to Frederick’s court in 1743 by the French government as an envoy and spy to gauge Frederick’s military intentions in the War of the Austrian Succession.[80]

Though deeply committed to the Marquise, Voltaire by 1744 found life at her château confining. On a visit to Paris that year, he found a new love—his niece. At first, his attraction to Marie Louise Mignot was clearly sexual, as evidenced by his letters to her (only discovered in 1957).[81][82] Much later, they lived together, perhaps platonically, and remained together until Voltaire’s death. Meanwhile, the Marquise also took a lover, the Marquis de Saint-Lambert.[83]