From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Eriugena” redirects here. For other uses, see Eriugena (disambiguation).

Not to be confused with John Duns Scotus.

| John Scotus Eriugena | |

|---|---|

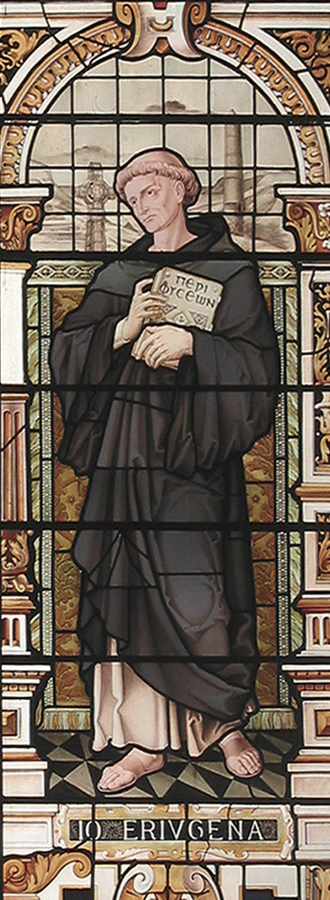

| Stained glass window in the chapel of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Depicted as an early Benedictine monk, holding his book De Divisione Naturae. Behind him, seen against the night-sky, are an Irish Round Tower and a Celtic cross. (1884) | |

| Born | 5 November, c. 815[3] Ireland |

| Died | c. 877 (age c. 62) probably West Francia or Kingdom of Wessex |

| Other names | Johannes Scottus Eriugena, Johannes Scotus Erigena, Johannes Scottigena |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism Augustinianism[1] |

| Main interests | Free Will, Intersubjectivity, Logic, Metaphysics, |

| Notable ideas | Four divisions of nature[2] |

| Part of a series on |

| Scholasticism |

|---|

| showSchools |

| showMajor works |

| showPrecursors |

| showPhilosophers |

| showRelated |

| vte |

John Scotus Eriugena,[a] also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena,[b] John the Scot, or John the Irish-born[4] (c. 800 – c. 877)[5] was an Irish Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet of the Early Middle Ages. Bertrand Russell dubbed him “the most astonishing person of the ninth century“.[6] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that he “is the most significant Irish intellectual of the early monastic period. He is generally recognized to be both the outstanding philosopher (in terms of originality) of the Carolingian era and of the whole period of Latin philosophy stretching from Boethius to Anselm“.[7]

He wrote a number of works, but is best known today for having written De Divisione Naturae (“The Division of Nature”), or Periphyseon, which has been called the “final achievement” of ancient philosophy, a work which “synthesizes the philosophical accomplishments of fifteen centuries”.[8] The principal concern of De Divisione Naturae is to unfold from φύσις (physis), which John defines as “all things which are and which are not”[9] the entire integrated structure of reality. Eriugena achieves this through a dialectical method elaborated through exitus and reditus, that interweaves the structure of the human mind and reality as produced by the λόγος (logos) of God.[10]

Eriugena is generally classified as a Neoplatonist, though he was not influenced directly by such pagan philosophers as Plotinus or Iamblichus. Jean Trouillard stated that, although he was almost exclusively dependent on Christian theological texts and the Christian Canon, Eriugena “reinvented the greater part of the theses of Neoplatonism”.[11]

He succeeded Alcuin of York (c. 735–804) as head of the Palace School at Aachen. He also translated and made commentaries upon the work of Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite and was one of the few Western European philosophers of his day who knew Greek, having studied it in Ireland.[12][13] A later medieval tradition recounts that Eriugena was stabbed to death by his students at Malmesbury with their pens, although this may rather be allegorical.[14]

Name

The form “Eriugena” is used by John Scotus to describe himself in one manuscript.[15] It means “Ireland (Ériu)-born”. “Scottus” in the Middle Ages was the Latin term for “Irish or Gaelic“, so his full name translates as “John, the Irish-born Gael”. “Scotti” was the late Latin term for the Irish people, with Ireland itself being Scotia (or in the Medieval period “Scotia Major”, to distinguish it from Scotia Minor, i.e. modern Scotland).[16] The spelling “Scottus” has the authority of the early manuscripts until perhaps the 11th century. Occasionally he is also named “Scottigena” (“Irish-born”) in the manuscripts.

According to Jorge Luis Borges, John’s byname may therefore be construed as the repetitious “Irish Irish”.[17]

He is not to be confused with the later, Scottish philosopher John Duns Scotus.

Life

Johannes Scotus Eriugena was educated in Ireland. He moved to France (about 845) at the invitation of Carolingian King Charles the Bald. He succeeded Alcuin of York (735–804), the leading scholar of the Carolingian Renaissance, as head of the Palace School.[12] The reputation of this school increased greatly under Eriugena’s leadership, and he was treated with indulgence by the king.[18] Whereas Alcuin was a schoolmaster rather than a philosopher, Eriugena was a noted Greek scholar, a skill which, though rare at that time in Western Europe, was used in the learning tradition of Early and Medieval Ireland, as evidenced by the use of Greek script in medieval Irish manuscripts.[12] He remained in France for at least thirty years, and it was almost certainly during this period that he wrote his various works.

Whilst eating with King Charles the Bald John broke wind. This was acceptable in Irish society but not in Frankish. The King is then said to have said “John tell me what separates a Scottus (Irishman) from a situs (a fool)?”. John replied “Oh just a table” and the king laughed.[4]

The latter part of his life is unclear. There is a story that in 882 he was invited to Oxford by Alfred the Great, labored there for many years, became abbot at Malmesbury, and was stabbed to death by his pupils with their styli.[18] Whether this is to be taken literally or figuratively is not clear,[19] and some scholars think it may refer to some other Johannes.[20] William Turner says the tradition has no support in contemporary documents and may well have arisen from some confusion of names on the part of later historians.[21]

He probably never left France, and the date of his death is generally given as 877.[22] From the evidence available, it is impossible to determine whether he was a cleric or a layman; the general conditions of the time make it likely that he was a cleric and perhaps a monk.[21]

Theology

Eriugena’s work is largely based upon Origen, St. Augustine of Hippo, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, St. Maximus the Confessor, and the Cappadocian Fathers. Eriugena’s overall view of reality, both human and divine, was strongly influenced by Neoplatonism. He viewed the totality of reality as a “graded hierarchy” cosmology of gradual declensions from the Godhead, similar to Proclus,[23] and likewise saw in all things a dual movement of procession and reversion: that every effect remains in its cause or constitutive principle, proceeds from it, and returns to it. According to Deirdre Carabine, both “ways” must be understood as intrinsically entwined and are not separate movements or processes.[24]

“For the procession of the creatures and the return of the same are so intimately associated in the reason which considers them that they appear to be inseparable the one from the other, and it is impossible for anyone to give any worthy and valid account of either by itself without introducing the other, that is to say, of the procession without the return and collection and vice versa.”[25]

John Scotus Eriugena was also a devout Catholic. Pittenger argues that, too often, those who have written about him seem to have pictured John as one who spent his life in the endeavor to dress up his own personal Neoplatonism in a thin Christian garb, but who never quite succeeded in disguising his real tendency. “This is untrue and unfair. Anyone who has taken the trouble to read Erigena, and not merely to read about him, and more particularly one who has studied the De Divisione Naturae sympathetically, cannot question the profound Christian faith and devotion of this Irish thinker nor doubt his deep love for Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God. In the middle of long and some what arid metaphysical discussions, one comes across occasional passages such as the following, surely the cry of a passionately Christian soul: O Domine Jesu, nullum aliud praemium, nullam aliam beatitudinem, nullum aliud gaudium a te postulo, nisi ut ad purum absque ullo errore fallacis theoriae verba tua, quae per tuum sanctum Spiritum inspirata sunt, intelligam (Migne ed., ioioB).”[26] The Greek Fathers were Eriugena’s favourites, especially Gregory the Theologian, and Basil the Great. Of the Latins he prized Augustine most highly. The influence of these was towards freedom and not towards restraint in theological speculation. This freedom he reconciled with his respect for the teaching authority of the Church as he understood it.[21]