Comedy Central • Jul 22, 2014 Jon tries to have a calm discussion about Israel’s ground offensive in the Gaza Strip, but he is quickly thwarted by The Best F#@king News Team Ever. Watch full episodes of The Daily Show now: http://on.cc.com/1zI8VsE About The Daily Show with Jon Stewart: The Daily Show with Jon Stewart was an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning program that looked at politics, pop culture, sports and entertainment through a sharp, reality-based lens. Stewart and The Best F#@king News Team Ever covered the day’s top stories like no one, using footage, field reports and guest interviews to deliver fake news that was even better than the real thing.

Tag Archives: Palestine

Irish minister Matt Carthy TD: “Palestine has the right to defend itself.”

Celtic fans show huge display of solidarity with Palestine

Islam Channel • Oct 25, 2023 • #celtic #palestine #newsDespite the club’s position on Palestine flags, Celtic fans created a huge display of solidarity before their match against Atletico Madrid.

Who Can Claim Palestine?

Oct 16, 2023 (tomaspueyo.medium.com)

One of the key questions in the conflict between Israel and Palestine is this: Who can legitimately claim the land? The underlying question is: Who deserves to have a state there, and to live there? To answer these questions, we need to understand the historic legitimacy of the claims of Israel and Palestine, and for that we must know who owned what, when.

In this article, I’ll refer to Palestine as the historical region of Palestine, a label that Romans adopted. It perdured for 2,000 years, and the British kept that label.

Ancient Israel

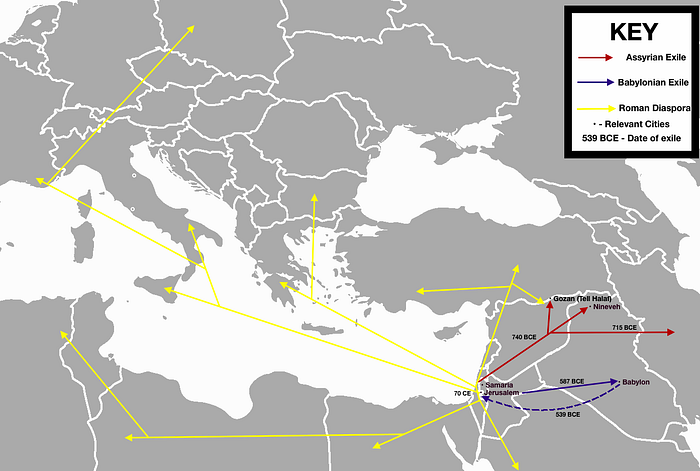

In the previous article, we covered the origin of the ancient Kingdom of Israel, and the Jews who inhabited it 3,000 years ago, how some were captured and sent to Babylon, and how they returned and formed a semi-autonomous kingdom.

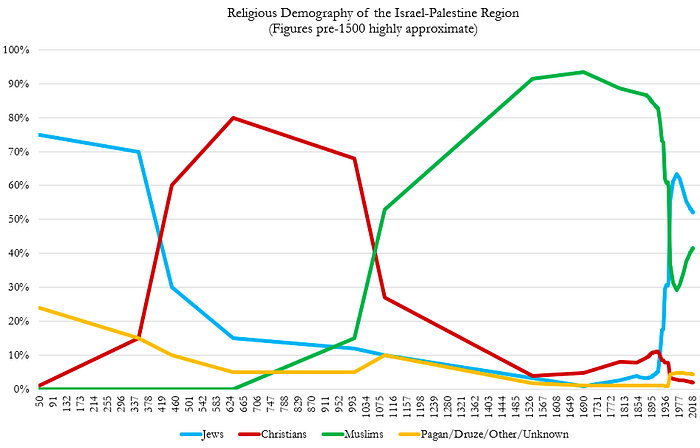

At that time, the number of Jews was growing until the Romans subdued them again. Their numbers started dwindling in clashes with the Roman Empire, which eventually triggered the Jewish Diaspora: Most of the Jews left the Levant and spread across countries.

After the Romans, the Byzantines took over the Levant, and then the Arab Muslims.

Arab and Muslim Rule

Muslim empires controlled the Levant for about 1,100 years between 650 AC and 1918, with the crusades as the only interlude, which lasted about 200 years.

Many of these early Muslim empires were Arab (Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, Fatimid, Ayyubid), but later ones were not (Seljuks were Persian, Mamluks were originally a warrior slave class from around the Black Sea, and the Ottomans were from Turkey).

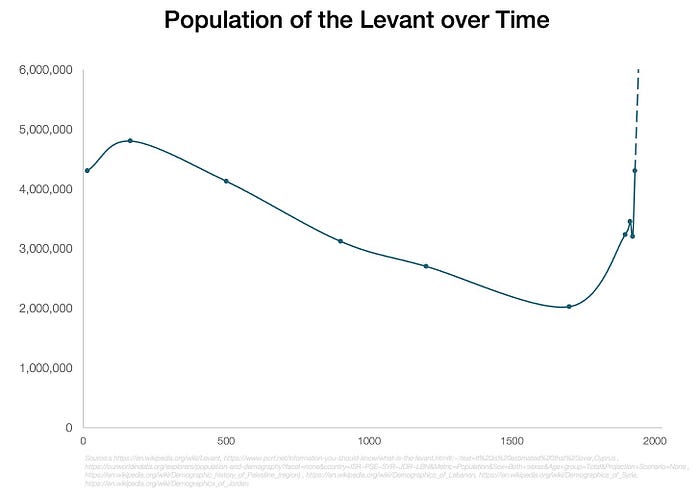

During the rule of all these empires, the many wars and the lack of local kingdoms probably affected the population negatively, so much so that by the early 20th century, the population of the Levant was lower than in Roman times.

Zionism

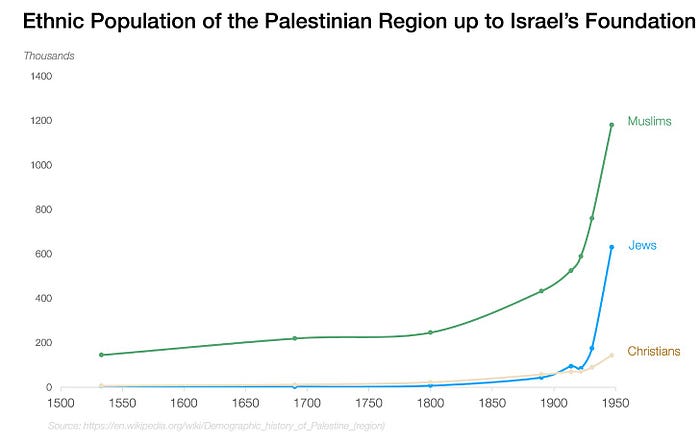

By the end of the 19th century, the share of Jewish population in Palestine was very low, antisemitism was rampant in Europe, and ideas of nations were en vogue. This is when Zionism appeared: the proposal to create a new Jewish state that could host and defend all Jews. Zionists created the typical elements of nation-building — a flag, a language — and decided on a place to recreate Israel. The obvious candidate was where it had all started, in the Levant, where Jews had dreamed of going back at some point.

In waves of immigration since the 1880s, hundreds of thousands of Jews arrived in the region, focusing on Palestine.

So many that, after thousands of years, their presence once more became sizable:

The strategy was conscious and thorough: Organize Jews across the world to buy land in Israel to establish themselves there.

By the early 1900s, tens of thousands of Jews were in Palestine. This brings us to the key pivotal point of the Palestinian conflict: World War I.

How to Split an Empire

It’s 1917. The Ottoman Empire is fighting alongside Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Allies are fighting the Central Powers. But there’s a stalemate. How can they tilt the balance?

One of their approaches is to open new fronts against the Ottomans in their overextended empire. So they enlist the Arabs, promising them a big nation in the Arabian Peninsula. This leads to the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans.

But the British also wanted the support of Jews, who now counted in the tens of thousands in the Ottoman region of Palestine. So they made the Balfour Declaration, promising them a “national home” in Palestine at the end of the war.

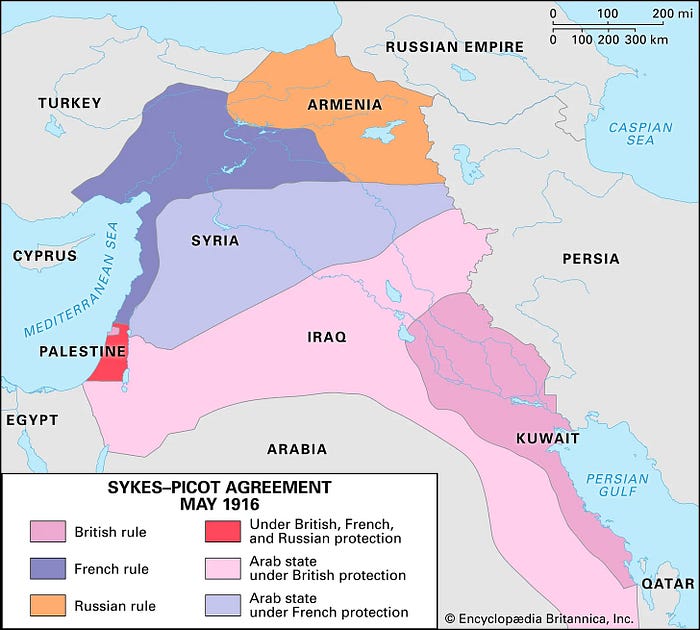

And of course, the Brits were not the only allied power in WWI. They had to decide how to split a conquered Ottoman Empire in the future with France, Russia, and Italy. So they signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which would split the region into French and British areas of influence.

The Arab leader, Hussein Bin Ali, didn’t accept this, but the Allied powers nevertheless went for it. In the following struggle, the UK created several protectorates in the region, of which two would be ruled by Hussein’s children (Iraq and Transjordan), and the Al Saud family took over most of Arabia:

The UK’s Quagmire: Mandatory Palestine

This left the UK in a weird position in the region they called Mandatory Palestine. They ruled it, but didn’t give it to Hussein. They had promised a homeland for Jews, but Arabs were a majority in the region and also wanted their own country. Remember, this is in the early 20th century, a time when the new idea of nationalism is exploding, and everybody wants land to build into a nation and rule, while the idea of the consent of the governed is taking hold: The legitimacy of a government depends on the agreement of its people.

Jews and Arabs had been clashing for years. Jews wanted their own country — and were OK with an Arab country — but the Arabs weren’t. They didn’t want to give up any land to the Jews. They also didn’t want any more Jewish immigration, given that the Zionist movement was in full swing, and Jewish immigrants kept coming.

Arabs and Jews clashed in 1928, 1929, and 1936. While local Arabs sold land to immigrating Jews, Arab leaders asked London to stop Jewish immigration, prevent land sales to Jews, and create an Arab country.

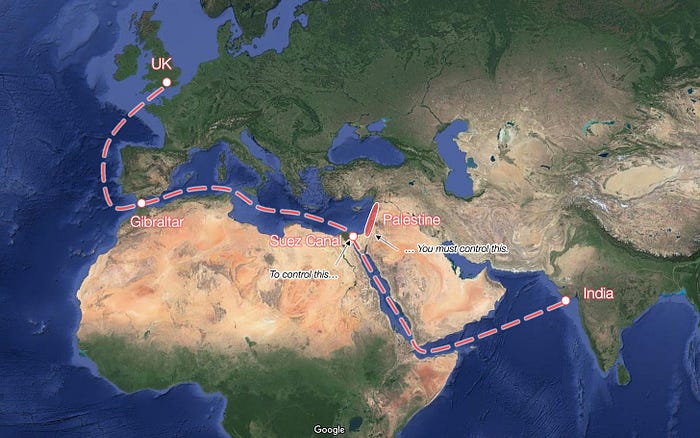

The British wanted to keep control over the region, because giving it away would have threatened the Suez Canal, a key artery for the UK in its communications with India.

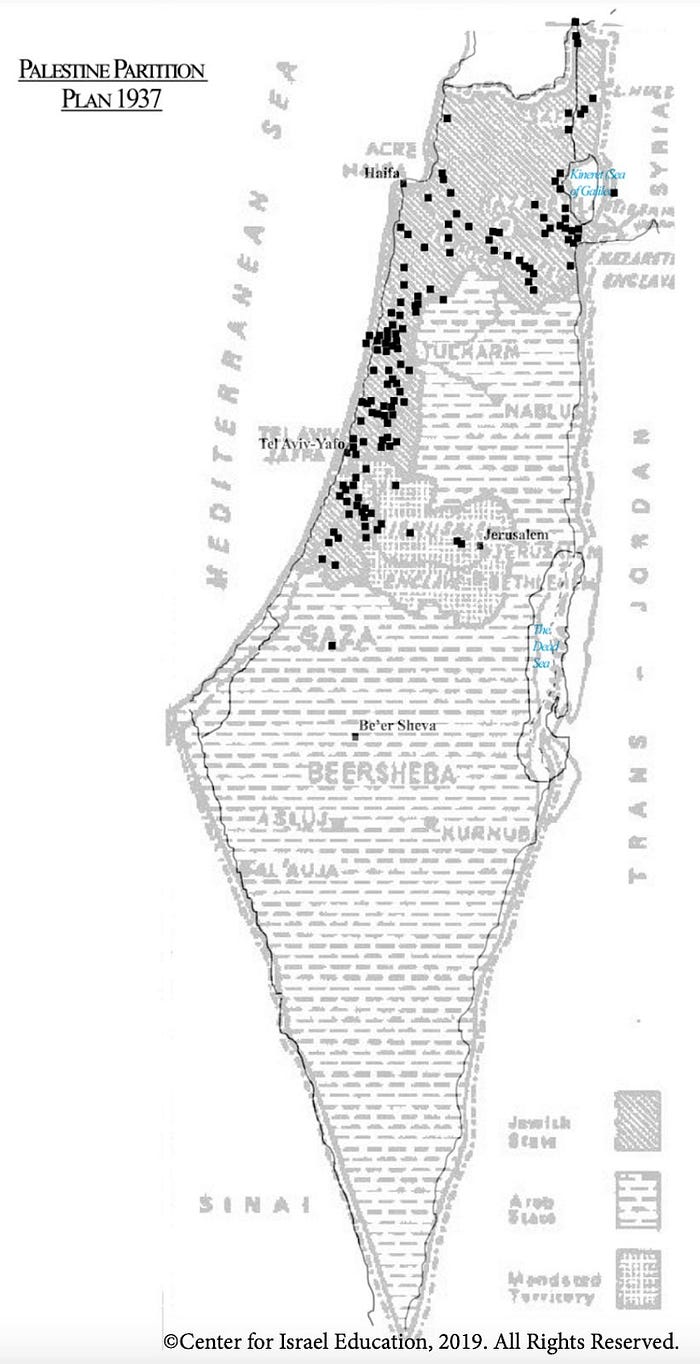

Issued in July 1937, the 400-page Peel Report ascertained that the underlying causes of the recent disturbances were the same as those in 1920, 1921, 1929, and 1933: the Arab desire for independence, the Arab hatred and fear of the Jewish national home and the determination of the Jewish national movement to realize its goals. It concluded that the two communities’ aspirations were irreconcilable, that the Mandate in its existing form was unworkable, and that Palestine should be partitioned into distinct Jewish and Arab entities. The Report attached a map of the proposed Arab and Jewish states and a neutral enclave for British control of the Holy Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. — Source.

The Arab community in Palestine utterly rejected the notion of partition, as did neighboring Arab leaders and states: in September 1937, in Bludan, Syria, a non-governmental pan-Arab Congress of over 400 Arab delegates rejected the partition of Palestine, declaring instead its goal as “liberation of the country and establishment of an Arab government.” The Zionist response was more nuanced, neither endorsing partition nor rejecting it outright. Zionists, while happy to hear that the British recommended partition, believed the time was not yet ripe and that the proposed Jewish state was too small.

London realized it couldn’t find a solution. So it invited Arab and Jewish leaders to hash it out. They couldn’t. At the same time, conflict in Europe was escalating, so the UK simply decided to freeze the situation with the 1939 White Paper by slowing down Jewish immigration and land acquisition, and suggesting a blurry “Jewish National Home within an independent Arab state”. Regardless, WWII broke out, and the Palestinian issue became secondary.

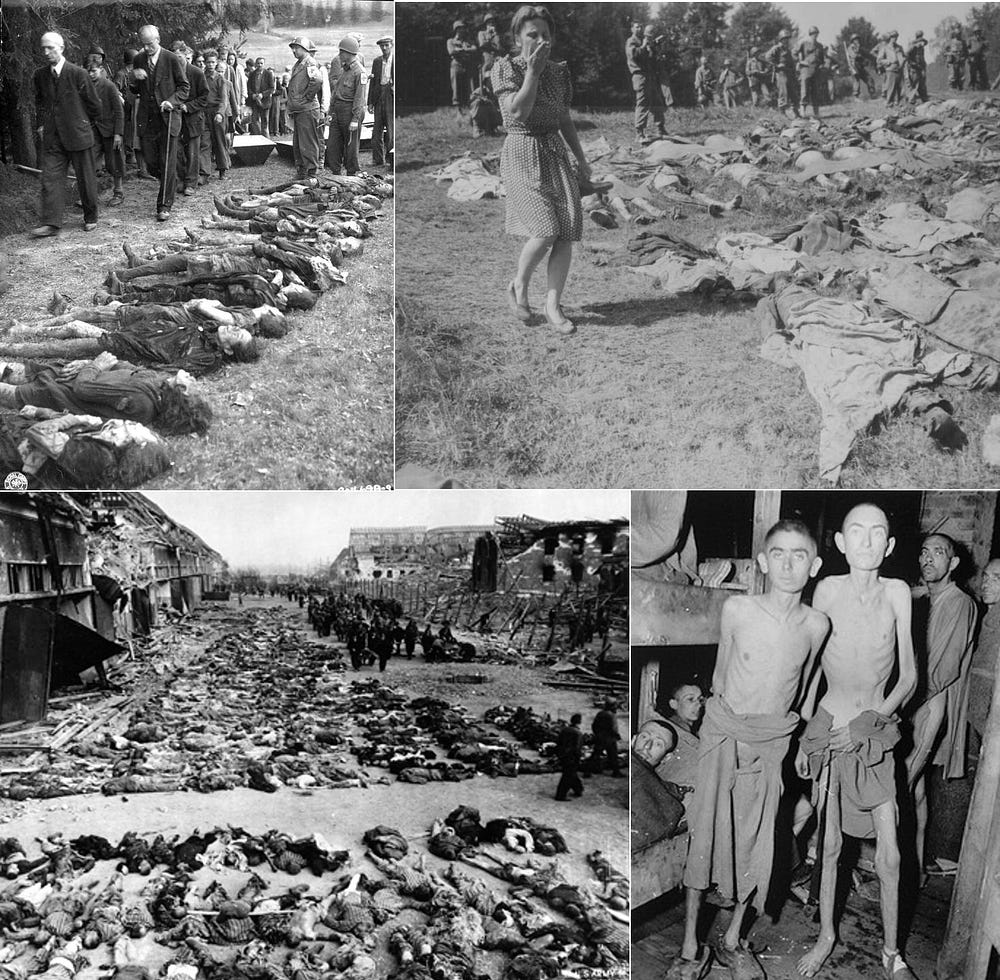

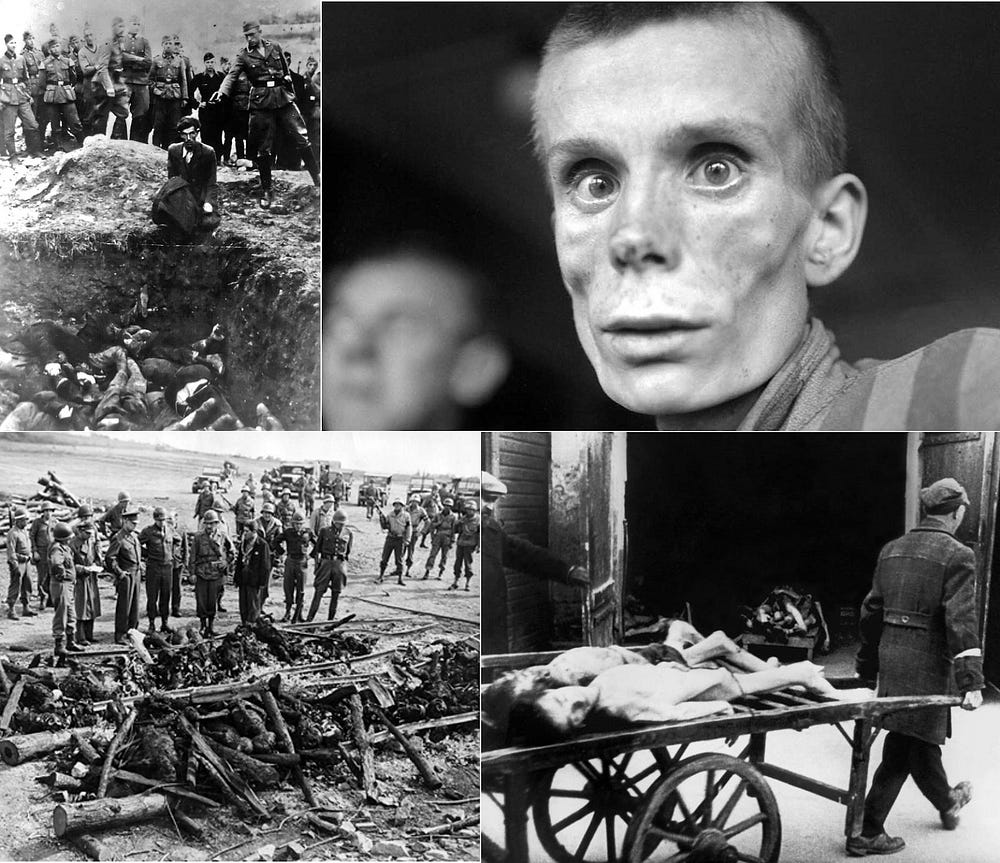

The Holocaust

As you know, six million Jews were exterminated during WWII — about one third of the world’s Jewish population at the time. I think images speak louder than words here.

What Should We Do after WWII?

The war gave a massive boost to the Zionist movement. Jews around the world yearned for a place where the Holocaust couldn’t happen to them anymore, and sympathy grew towards them, especially in the Western World.

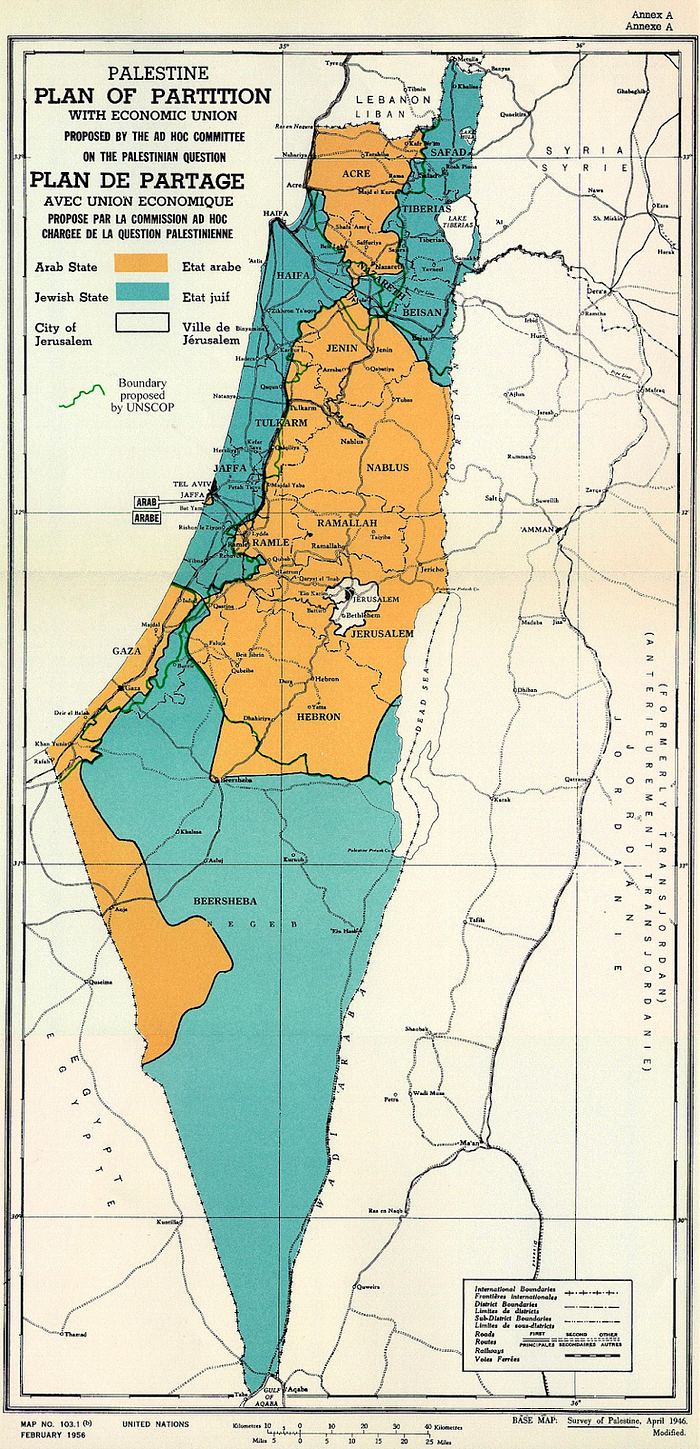

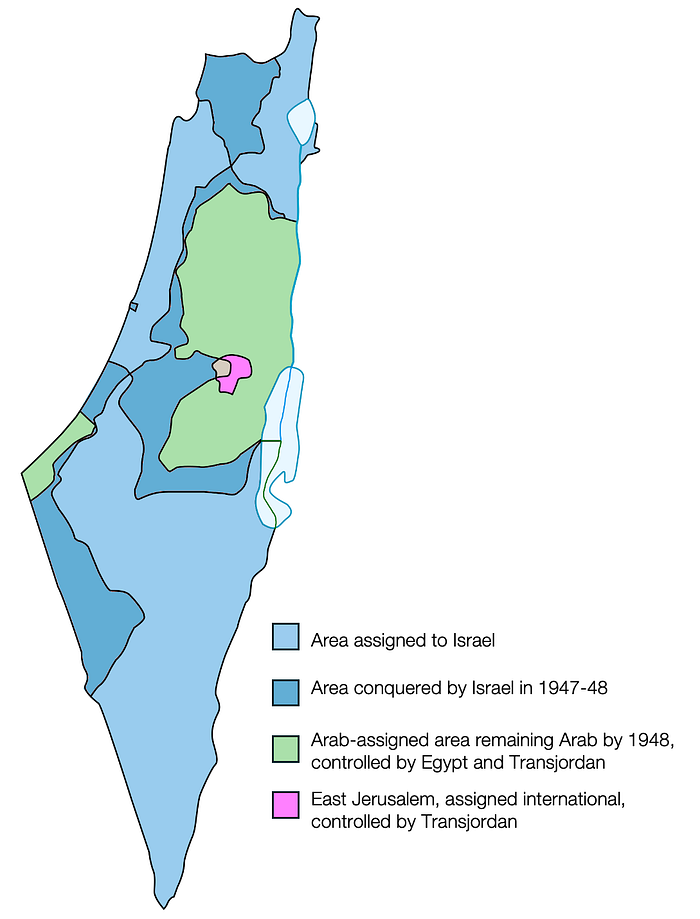

At the same time, the UK started withdrawing from its colonies. Given the complexity of the Palestinian situation, it just dropped the problem like a hot potato and asked the UN to come up with a plan. The UN proposed a two-state solution:

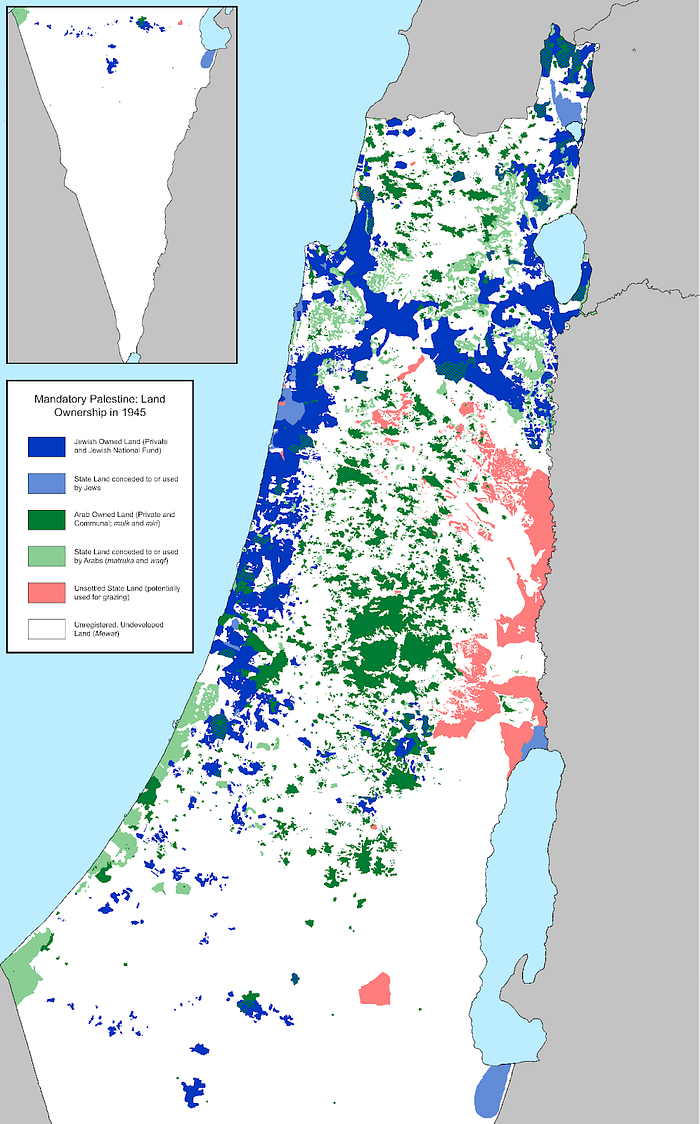

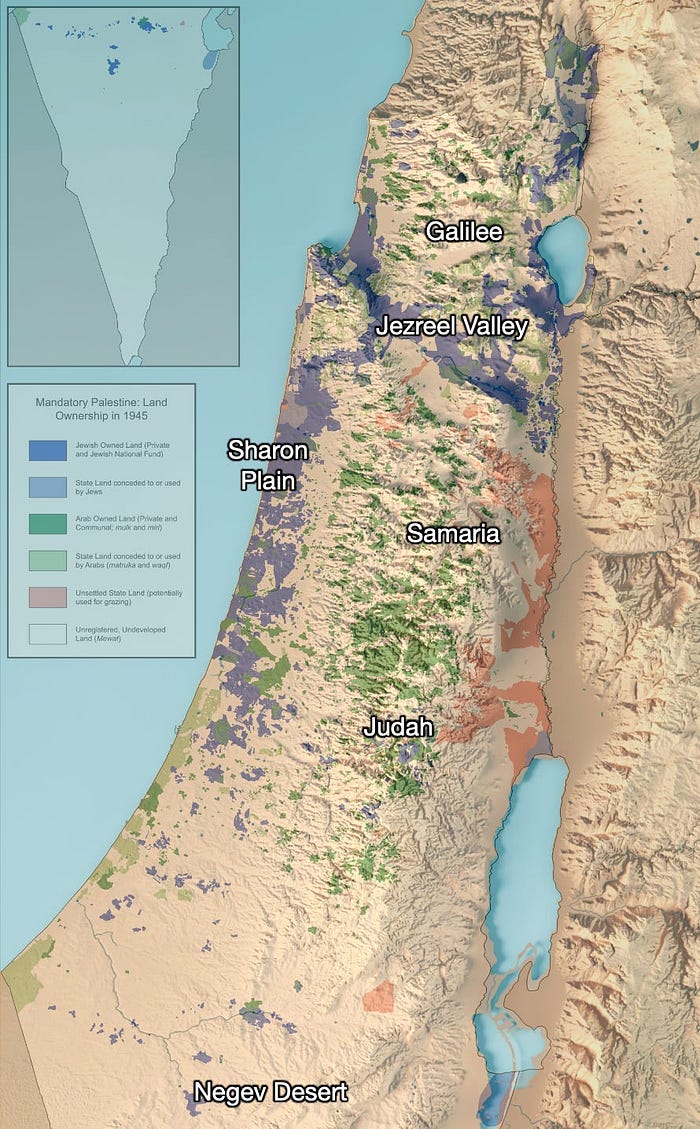

This map had changed substantially from the one proposed by the UK a few years earlier. It gave a big chunk of the north of the country (Galilee) to the Arabs, but it gave the Jews the lion’s share of the Negev desert in the south. This increased the allocation of land to the Jews. Why? These were the settled areas at the time:

Jews had focused their settlements in specific areas: the northern coast, the Jezreel Valley, Galilee, and the Negev desert. They had not settled the southern coast and central mountains.

The UN had several goals. The main one was to provide land to each side that would reflect where they lived, as well as to make room for further Jewish immigration. The result is that areas with Jewish majority or heavy minority were allocated to Jews. Meanwhile, the Negev desert, which represents 60% of the land of Israel even today, was very sparsely populated but had been intensely settled by Jews in the previous decade. It was allocated to Israel.

Another goal of the UN was to allow each state to be as contiguous as possible. Contiguity was important for economic and defense purposes, but this map made it really awkward, with two narrow points connecting disjointed parts of each country.

The result of all of this was that the existence of a Jewish country would entail providing 56% of the land to one third of the population, while creating two semi-split countries.

At the UN, the plan was approved by the General Assembly by over 66% of the vote.

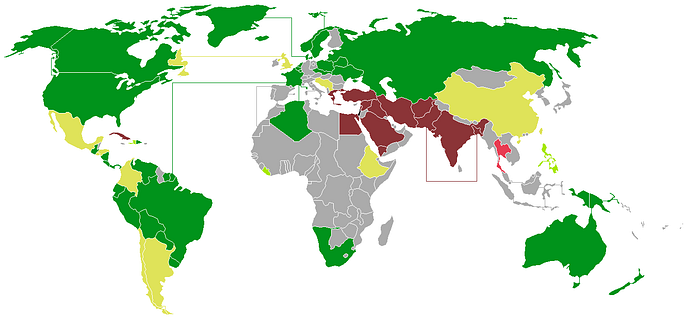

The Jews accepted it, while Arab and Muslim countries didn’t.

The Arab reaction covered the entire spectrum, from the thought that this deal was good because it would preempt Israelis from furthering their advantages, to the desire to commit a genocide against them. The most common reaction was one of preferring war to giving in to a two-state solution.

Personally I hope the Jews do not force us into this war because it will be a war of elimination and it will be a dangerous massacre which history will record similarly to the Mongol massacre or the wars of the Crusades. We will sweep them [the Jews] into the sea. — Azzam Pasha, General Secretary of the Arab League.

We shall eradicate Zionism. — Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli

[Arabs will] continue fighting until the Zionists are annihilated. — Haj Amin al-Husseini, Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

So Arab countries went to war.

The Formation of the New Israel

The British Mandate in Palestine ended on May 14th 1948.

That day, Israel declared its independence.

The day after, Arab countries attacked.

Egypt, Transjordan (now Jordan), Syria, and expeditionary forces from Iraq entered Palestine in unison.

Somehow, the Israelis won the war and expanded their land beyond what was assigned to them by the UN in 1947.

This was the third opportunity for Arabs to create a Palestinian independent state, after the British and UN proposals. But Egypt and Transjordan had different aims. They simply took over the Arab regions for themselves. Egypt took over the Gaza strip (the small green band on the left), and Transjordan took over the West Bank (the bigger green blob on the right). Israel signed truces with all its neighbors, but not lasting peace agreements.

Around 750,000 Arab Palestinians fled or were expelled from the Israeli areas, in what they call the Nakba (“disaster”). The causes are complex, and range from straight expulsion by Israeli forces to requests from Arab leaders for the population to leave, to fear of hostilities, or confidence they could return after the conflict. About 150,000 Arabs remained and became Israeli citizens. Arab nations refused to absorb Palestinian refugees, instead keeping them in refugee camps while insisting that they be allowed to return.

Another UN resolution supported the right to return of these refugees.

This reflects a similar migration of Jews from Arab countries. Between 1948 and 1970, around 900,000 Jews emigrated from Muslim countries around the world — mostly Arab — into Israel. In some cases, they were attracted by the Israeli project. This was the majority of emigration from Morocco, Algeria, Tunis, or Turkey. However, in many other countries like Egypt, Iraq, Syria, or Sudan, Jews were persecuted.

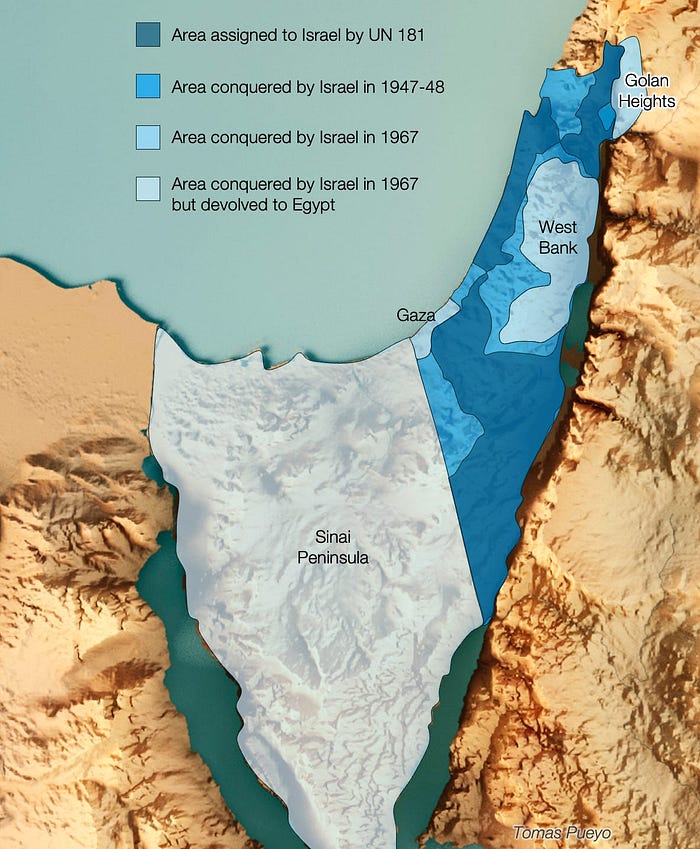

The Expansion of Israel

Israel would attack Egypt in a smaller war in 1956 for the Suez Canal and to keep access to the oceans from its southern tip.

About ten years later, Egypt blocked that access and prepared for another war with Israel, amassing military personnel along the border and asking UN forces to leave the area. The Jewish state preempted an attack and targeted the air forces of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, eliminating them in the first day of what’s called the six-day war. Jordanian and Syrian forces were misled by Egypt into thinking it was winning and started shelling Israel. Israel counterattacked and took over Gaza, the Sinai peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights.

About 300,000 Palestinians left the West Bank, and about 100,000 Syrians left the Golan Heights.

Six years later, in 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel again, in the Yom Kippur War. Initially they were successful, before being pushed back by Israeli forces, which advanced on Cairo and Damascus, the capitals of Egypt and Syria.

After this, Egypt decided to bid for peace with Israel. Israel returned the Sinai, and they signed peace agreements following the Camp David Accords of 1978. In 1994, Israel signed a peace treaty with Jordan, which relinquished its claims on the West Bank. In 2020, under the Abraham Accords, Israel signed peace treaties with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. In the last 50 years, Israel has gone from having no relations with the majority of countries in the world, to having relations with all countries but for some Muslim ones and some dictatorships.

I haven’t talked much yet about the Arab Palestinians who live in occupied territories. I will soon. But we already have a bunch of information from which to start drawing conclusions.

Who Deserves the Land of Palestine?

It depends. Who do you want?

We can’t answer this question before acknowledging here the massive biases. People don’t have hard moral rules that they apply consistently across situations. They have an intuition, and then they try to justify it morally.

This, of course, is toxic in a situation like this one, where there is a small land that must be split between two parties. The size of the pie is settled, and we can only fight for the biggest slice. So instead of having a predetermined answer and then trying to justify it, we should come up with moral rules of legitimacy, and see where they take us. So what factors decide whether a land should belong to one group or the other?

Who ruled first?

Israel.

They were there 3,000 years ago. They were there 1,600 years before Islam even existed, or Arabs conquered the region.

But that’s a long time ago. Who controlled the land first, but recently?

How recently? How do you know what’s the relevant recency? When should you start counting?

If you start counting 3,000 years ago, that’s Jews.

2,000 years ago, still Jews.

The centuries before 1900? The area was controlled by the Mamluk, who were Turkic soldiers from Egypt, and then the Ottomans, who were Turkic. Both were Muslim, but neither was Arabic. The Seljuk were not Arab either.

There was never an independent Arab state in the region. There was Arab rule, however, but the most recent one was about 700 years ago or so, the Ayyubid Sultanate. Unless you count the Mamluks, in which case it was 500 years ago.

What about Muslim rule, not Arab rule?

This is something that many think but few voice out loud, I believe. There is a significant religious component in all of this. Indeed, the region was ruled by Muslims for about 1,300 years, between about 650 and 1918, with a 200 year hiatus due to the Crusaders. It has not had Muslim rule since.

Should we consider religion as a basis for legitimacy of a state there?

Maybe. Should there be a Muslim state in Palestine because the region was ruled by Muslims for over one thousand years?

What about the fact that Jews ruled there for over 1,000 years?

When is the appropriate time to take this into consideration?

Israel is officially a Jewish state. Does it deserve at least one state in the world, since Muslims have plenty?

Should other religions be able to claim a country?

Who rules doesn’t matter, what matters is the people. Who was there first?

The Canaanites, from whom both Arabs and Jews in the region descend.

After them, it was the Jews, who had a strong presence there for 1,100 years, and some stayed there for 500 years more before Arabs started appearing in the region.

What about more recently?

In Israel, Jews are a majority. In the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank, Arabs are a majority.

What about just before the Israelis came back during the Zionist movement?

There was a strong Arab majority.

Was it a lot of people?

No. The population was pretty small at the time, as this region was neither contested nor important strategically, and its economy had suffered in the previous centuries.

What about the *religion* of the people?

Israel and Palestine had a majority of Jews until the late Roman Empire, for about 1,500 years.

Then for about 600 years it was a Christian majority. Should it be Israeli because Jews were there first?

Christians fought the crusades because at some point the Arabs decided to kick them out. Should the region be Christian because the Arab Muslim colonizers kicked them out?

Muslims were probably a majority for the last 900 years, before Jews took over. Are these the ones that really count? Or did they prevail the very same way as Arab Muslims did before them?

The UK is a majority-Christian country. It won the area fair and square. Should the region be Christian?

What about what’s morally right?

On one hand, Jews suffered the Holocaust. Maybe they deserve a country to ensure that never happens again? Remember, they don’t have any, but there’s plenty of Arab and Muslim countries. Does that matter?

On the other hand, they arrived and took over the local land. Some consider this colonization. I don’t think this qualifies, as colonizers have a home country and want to extract wealth from the colony. Jews don’t want to extract wealth from Israel. They made it their home. Maybe that’s reprehensible and they should leave?

But also the local population colonized it from other populations. It’s assholes all the way down. Dozens of empires have been battling for this piece of land for centuries. Which one is the legitimate one?

What about state building?

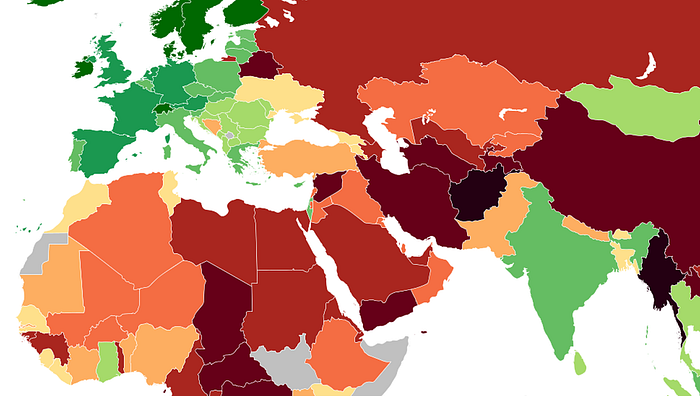

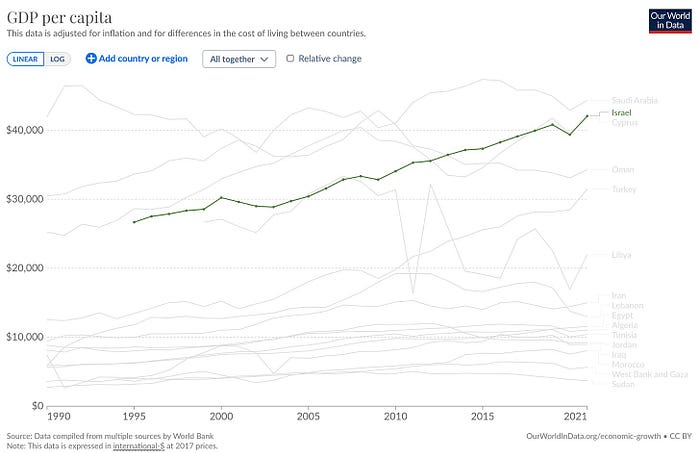

Israel is the most democratic country in the region by far. It has created a rich and prosperous country. Excluding petrostates, Israel is the richest across the region and compared to other Arab states, the one with the highest human development index, the lowest corruption, the highest business freedom, rule of law, innovation…

Surely we want more successful countries like this?

Well… Do you want your country to stop existing because it stagnates? Should Europeans colonize Africa again to make sure it grows?

I’m going to assume you don’t think so. So even if you *root* for this type of country, it is not a legitimate basis on which to decide whether one deserves to exist or not.

What about might is right?

Then Israel currently controls the land and should keep it. But then this entices imperial powers to conquer their weaker neighbors. If you don’t like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or you don’t want China to invade Taiwan, you shouldn’t be cheering Israel for controlling Palestine by force.

Should we penalize the Palestinians because Arabs had plenty of opportunities to get an Arab state?

It’s true that Arabs have had many occasions to get an Arab state: the British proposal in the 1930s, the UN proposal, several offers from Israel since…

But honestly, who could blame them for it? From their perspective, in each one of these proposals, they were getting a worse deal than what had been the reality a few decades earlier. And every time, they were just one successful war away from taking over the region. So they gambled, and they lost. The current situation is the consequence. Should it mean that millions of people who feel Palestinian and are governed by an occupying force don’t deserve a country? I don’t think so.

What would you have done in their position? A bunch of immigrants systematically come to the area where you live, and a few decades later they demand their own country. What would you do?

Plus, in many of these situations, it was not the Palestinians voting, but other Arab countries, which, as we’ve seen, don’t usually have the best for the Palestinians in mind. For example, Jordan took over the West Bank, and Egypt took over Gaza when they had the opportunity.

So who deserves the land then?!

This question has no answer. You can simply choose whatever suits you to legitimize your position. Both have many legitimate claims. If you wanted to be really objective, you would need to create a mathematical formula that accounts for things like rulers, populations, their sizes, and a factor to discount time, so that more recent times count more than older times. Of course, whoever does that would likely tweak the parameters to make their answer seem like the right one. Jews might want to discount time a lot (or very little) to win, because they’ve controlled the land both recently and long ago. They might also weigh the ethnicity that ruled more heavily, since Arabs haven’t ruled the area for centuries. Meanwhile, Arabs would weigh religion and the ethnicity of the local populations more, but not too recently.

So nobody deserves this land, because for the last 3,000 years, dozens of peoples have fought for it, all until very recently, and the mixes of religion, rulers, and ethnicities are too complex.

How should we decide then?

Geography, history, legality, people, rulers, morality… So many factors. The problem is that these are easy to bias. Those who use this type of bias tend to adapt their rules depending on the situation, to favor them. But that makes no sense. If somebody thinks the region should be Israeli because that’s right for Jews, or vice-versa, who’s to say that this rule should be limited to a specific area? Why not make the entire world that way?

We need rules that are objective and can be accepted by all.

Internationally, the set of rules that determines statehood is the Montevideo Convention:

The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

Additionally, regions can’t be countries, and countries can’t gain independence through military action.

As of today, in my humble opinion, neither Israel, nor Gaza, nor the West Bank respect these four. The population in the West Bank keeps changing because of Jewish settlements. Israel’s territory keeps changing for the same reason. Hamas is not a government for Gaza, and is in no position to enter into relations with the other states. None of the groups have a total claim on the region. Of course, nobody would say that none of these countries deserve their own state.

Another important factor is that political legitimacy comes from the consent of the people. In other words, self-determination. This resonates with me, because it’s the translation of freedom at the level of the people. If a large majority of the people in a region consistently believes over time that it should belong to a separate country, and it emphatically pushes for this to happen, it should be respected.

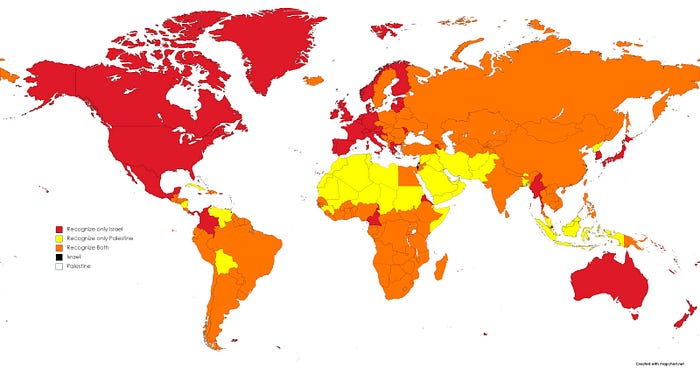

Another factor is international recognition.

The truth is that the vast majority of countries recognize both countries, and the only countries that recognize only one of them are allies of one side or the other. In other words, they’re biased. Having lived in many countries that don’t recognize Palestine, I can confidently say that everybody in these countries knows Palestine is a reality.

In summary, who deserves a claim on Palestine?

Israelis make up the vast majority of the population in Israel, and have done so for decades. They want their state to be independent. Most countries recognize Israel exists. It’s a stable country, with a permanent population, defined territory, and government. It has a strong historic, moral, and geographic claim. It deserves to exist.

Similarly, Palestinians make up the vast majority of the population in Palestinian territories, and have done so for decades. They want their state to be independent. Most countries recognize Palestine exists, even if not officially. It’s a country with stable borders, with a permanent population, and defined territory. It has a strong historic, moral, and geographic claim. Despite what Westerners think, their government has been stable (both Fatah and Hamas in their respective territories have governed for over 15 years now). Palestine deserves to exist, even if it needs help getting its government to reasonable international standards.

Israel and Palestine deserve to be countries.

If you’ve been debating the roles of Israel and Palestine in the past few days with somebody, share this article with them. I hope it helps you reconcile different points of view.

How do you go from this conclusion to actually making it happen?

What about the settlements?

What about the right to return?

What about safety on each side?

What about the government failure on the Palestinian side?

I’m going to cover these next, and for that, we will tackle the geopolitics of Palestine next. To receive my emails, scroll down until you see my name and click on the little envelope to the right.

2 MSc in Engineering. Stanford MBA. Ex-Consultant. Creator of applications with >20M users. Currently leading a billion-dollar business @ Course Hero

There Is a Jewish Hope for Palestinian Liberation. It Must Survive.

Oct. 14, 2023 (NYTimes.com)

By Peter Beinart

Mr. Beinart is a journalist and commentator who writes frequently about American foreign policy.

In 1988, bombs exploded at restaurants, sporting events and arcades in South Africa. In response, the African National Congress, then in its 77th year of a struggle to overthrow white domination, did something remarkable: It accepted responsibility and pledged to prevent its fighters from conducting such operations in the future. Its logic was straightforward: Targeting civilians is wrong. “Our morality as revolutionaries,” the A.N.C. declared, “dictates that we respect the values underpinning the humane conduct of war.”

Historically, geographically and morally, the A.N.C. of 1988 is a universe away from the Hamas of 2023, so remote that its behavior may seem irrelevant to the horror that Hamas unleashed last weekend in southern Israel. But South Africa offers a counter-history, a glimpse into how ethical resistance works and how it can succeed. It offers not an instruction manual, but a place — in this season of agony and rage — to look for hope.

There was nothing inevitable about the A.N.C.’s policy, which, as Jeff Goodwin, a New York University sociologist, has documented, helped ensure that there was “so little terrorism in the anti-apartheid struggle.” So why didn’t the A.N.C. carry out the kind of gruesome massacres for which Hamas has become notorious? There’s no simple answer. But two factors are clear. First, the A.N.C.’s strategy for fighting apartheid was intimately linked to its vision of what should follow apartheid. It refused to terrify and traumatize white South Africans because it wasn’t trying to force them out. It was trying to win them over to a vision of a multiracial democracy.

Second, the A.N.C. found it easier to maintain moral discipline — which required it to focus on popular, nonviolent resistance and use force only against military installations and industrial sites — because its strategy was showing signs of success. By 1988, when the A.N.C. expressed regret for killing civilians, more than 150 American universities had at least partially divested from companies doing business in South Africa, and the United States Congress had imposed sanctions on the apartheid regime. The result was a virtuous cycle: Ethical resistance elicited international support, and international support made ethical resistance easier to sustain.

In Israel today, the dynamic is almost exactly the opposite. Hamas, whose authoritarian, theocratic ideology could not be farther from the A.N.C.’s, has committed an unspeakable horror that may damage the Palestinian cause for decades to come. Yet when Palestinians resist their oppression in ethical ways — by calling for boycotts, sanctions and the application of international law — the United States and its allies work to ensure that those efforts fail, which convinces many Palestinians that ethical resistance doesn’t work, which empowers Hamas.

The savagery Hamas committed on Oct. 7 has made reversing this monstrous cycle much harder. It could take a generation. It will require a shared commitment to ending Palestinian oppression in ways that respect the infinite value of every human life. It will require Palestinians to forcefully oppose attacks on Jewish civilians, and Jews to support Palestinians when they resist oppression in humane ways — even though Palestinians and Jews who take such steps will risk making themselves pariahs among their own people. It will require new forms of political community, in Israel-Palestine and around the world, built around a democratic vision powerful enough to transcend tribal divides. The effort may fail. It has failed before. The alternative is to descend, flags waving, into hell.

As Jewish Israelis bury their dead and recite psalms for their captured, few want to hear at this moment that millions of Palestinians lack basic human rights. Neither do many Jews abroad. I understand; this attack has awakened the deepest traumas of our badly scarred people. But the truth remains: The denial of Palestinian freedom sits at the heart of this conflict, which began long before Hamas’s creation in the late 1980s.

Most of Gaza’s residents aren’t from Gaza. They’re the descendants of refugees who were expelled, or fled in fear, during Israel’s war of independence in 1948. They live in what Human Rights Watch has called an “open-air prison,” penned in by an Israeli state that — with help from Egypt — rations everything that goes in and out, from tomatoes to the travel documents children need to get lifesaving medical care. From this overcrowded cage, which the United Nations in 2017 declared “unlivable” for many residents in part because it lacks electricity and clean water, many Palestinians in Gaza can see the land that their parents and grandparents called home, though most may never set foot in it.

Palestinians in the West Bank are only slightly better off. For more than half a century, they have lived without due process, free movement, citizenship or the ability to vote for the government that controls their lives. Defenseless against an Israeli government that includes ministers openly committed to ethnic cleansing, many are being driven from their homes in what Palestinians compare to the mass expulsions of 1948. Americans and Israeli Jews have the luxury of ignoring these harsh realities. Palestinians do not. Indeed, the commander of Hamas’s military wing cited attacks on Palestinians in the West Bank in justifying its barbarism last weekend.

Just as Black South Africans resisted apartheid, Palestinians resist a system that has earned the same designation from the world’s leading human rights organizations and Israel’s own. After last weekend, some critics may claim Palestinians are incapable of resisting in ethical ways. But that’s not true. In 1936, during the British mandate, Palestinians began what some consider the longest anticolonial general strike in history. In 1976, on what became known as Land Day, thousands of Palestinian citizens demonstrated against the Israeli government’s seizure of Palestinian property in Israel’s north. The first intifada against Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which lasted from roughly 1987 to 1993, consisted primarily of nonviolent boycotts of Israeli goods and a refusal to pay Israeli taxes. While some Palestinians threw stones and Molotov cocktails, armed attacks were rare, even in the face of an Israeli crackdown that took more than 1,000 Palestinian lives. In 2005, 173 Palestinian civil society organizations asked “people of conscience all over the world to impose broad boycotts and implement divestment initiatives against Israel similar to those applied to South Africa in the apartheid era.”

But in the United States, Palestinians received little credit for trying to follow Black South Africans’ largely nonviolent path. Instead, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement’s call for full equality, including the right of Palestinian refugees to return home, was widely deemed antisemitic because it conflicts with the idea of a state that favors Jews.

It is true that these nonviolent efforts sit uncomfortably alongside an ugly history of civilian massacres: the murder of 67 Jews in Hebron in 1929 by local Palestinians after Haj Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, claimed Jews were about to seize Al Aqsa Mosque; the airplane hijackings of the late 1960s and 1970s carried out primarily by the leftist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Yasir Arafat’s nationalist Fatah faction; the 1972 assassination of Israeli athletes in Munich carried out by the Palestinian organization Black September; and the suicide bombings of the 1990s and 2000s conducted by Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Fatah’s Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, whose victims included a friend of mine in rabbinical school who I dreamed might one day officiate my wedding.

And yet it is essential to remember that some Palestinians courageously condemned this inhuman violence. In 1979, Edward Said, the famed literary critic, declared himself “horrified at the hijacking of planes, the suicidal missions, the assassinations, the bombing of schools and hotels.” Rashid Khalidi, a Palestinian American historian, called the suicide bombings of the second intifada “a war crime.” After Hamas’s attack last weekend, a member of the Israeli parliament, Ayman Odeh, among the most prominent leaders of Israel’s Palestinian citizens, declared, “It is absolutely forbidden to accept any attacks on the innocent.”

Tragically, this vision of ethical resistance is being repudiated by some pro-Palestinian activists in the United States. In a statement last week, National Students for Justice in Palestine, which is affiliated with more than 250 Palestinian solidarity groups in North America, called Hamas’s attack “a historic win for the Palestinian resistance” that proves that “total return and liberation to Palestine is near” and added, “from Rhodesia to South Africa to Algeria, no settler colony can hold out forever.” One of its posters featured a paraglider that some Hamas fighters used to enter Israel.

The reference to Algeria reveals the delusion underlying this celebration of abduction and murder. After eight years of hideous war, Algeria’s settlers returned to France. But there will be no Algerian solution in Israel-Palestine. Israel is too militarily powerful to be conquered. More fundamentally, Israeli Jews have no home country to which to return. They are already home.

Mr. Said understood this. “The Israeli Jew is there in the Middle East,” he advised Palestinians in 1974, “and we cannot, I might even say that we must not, pretend that he will not be there tomorrow, after the struggle is over.” The Jewish “attachment to the land,” he added, “is something we must face.” Because Mr. Said saw Israeli Jews as something other than mere colonizers, he understood the futility — as well as the immorality — of trying to terrorize them into flight.

The failure of Hamas and its American defenders to recognize that will make it much harder for Jews and Palestinians to resist together in ethical ways. Before last Saturday, it was possible, with some imagination, to envision a joint Palestinian-Jewish struggle for the mutual liberation of both peoples. There were glimmers in the protest movement against Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul, through which more and more Israeli Jews grasped a connection between the denial of rights to Palestinians and the assault on their own. And there were signs in the United States, where almost 40 percent of American Jews under the age of 40 told the Jewish Electoral Institute in 2021 that they considered Israel an apartheid state. More Jews in the United States, and even Israel, were beginning to see Palestinian liberation as a form of Jewish liberation as well.

That potential alliance has now been gravely damaged. There are many Jews willing to join Palestinians in a movement to end apartheid, even if doing so alienates us from our communities, and in some cases, our families. But we will not lock arms with people who cheer the kidnapping or murder of a Jewish child.

The struggle to persuade Palestinian activists to repudiate Hamas’s crimes, affirm a vision of mutual coexistence and continue the spirit of Mr. Said and the A.N.C. will be waged inside the Palestinian camp. The role of non-Palestinians is different: to help create the conditions that allow ethical resistance to succeed.

Palestinians are not fundamentally different from other people facing oppression: When moral resistance doesn’t work, they try something else. In 1972, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, which was modeled on the civil rights movement in the United States, organized a march to oppose imprisonment without trial. Although some organizations, most notably the Provisional Irish Republican Army, had already embraced armed resistance, they grew stronger after British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians in what became known as Bloody Sunday. By the early 1980s, the Irish Republican Army had even detonated a bomb outside Harrods, the department store in London. As Kirssa Cline Ryckman, a political scientist, observed in a 2019 paper on why certain movements turn violent, a lack of progress in peaceful protest “can encourage the use of violence by convincing demonstrators that nonviolence will fail to achieve meaningful concessions.”

Israel, with America’s help, has done exactly that. It has repeatedly undermined Palestinians who sought to end Israel’s occupation through negotiations or nonviolent pressure. As part of the 1993 Oslo Accords, the Palestine Liberation Organization renounced violence and began working with Israel — albeit imperfectly — to prevent attacks on Israelis, something that revolutionary groups like the A.N.C. and the Irish Republican Army never did while their people remained under oppression. At first, as Khalil Shikaki, a Palestinian political scientist, has detailed, Palestinians supported cooperation with Israel because they thought it would deliver them a state. In early 1996, Palestinian support for the Oslo process reached 80 percent while support for violence against Israelis dropped to 20 percent.

The 1996 election of Benjamin Netanyahu, and the failure of Israel and its American patron to stop settlement growth, however, curdled Palestinian sentiment. Many Jewish Israelis believe that Ehud Barak, who succeeded Mr. Netanyahu, offered Palestinians a generous deal in 2000. Most Palestinians, however, saw Mr. Barak’s offer as falling far short of a fully sovereign state along the 1967 lines. And their disillusionment with a peace process that allowed Israel to entrench its hold over the territory on which they hoped to build their new country ushered in the violence of the second intifada. In Mr. Shikaki’s words, “The loss of confidence in the ability of the peace process to deliver a permanent agreement on acceptable terms had a dramatic impact on the level of Palestinian support for violence against Israelis.” As Palestinians abandoned hope, Hamas gained power.

After the brutal years of the second intifada, in which Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups repeatedly targeted Israeli civilians, President Mahmoud Abbas of the Palestinian Authority and Salam Fayyad, his prime minister from 2007 to 2013, worked to restore security cooperation and prevent anti-Israeli violence once again. Yet again, the strategy failed. The same Israeli leaders who applauded Mr. Fayyad undermined him in back rooms by funding the settlement growth that convinced Palestinians that security cooperation was bringing them only deepening occupation. Mr. Fayyad, in an interview with The Times’s Roger Cohen before he left office in 2013, admitted that because the “occupation regime is more entrenched,” Palestinians “question whether the P.A. can deliver. Meanwhile, Hamas gains recognition and is strengthened.”

As Palestinians lost faith that cooperation with Israel could end the occupation, many appealed to the world to hold Israel accountable for its violation of their rights. In response, both Democratic and Republican presidents have worked diligently to ensure that these nonviolent efforts fail. Since 1997, the United States has vetoed more than a dozen United Nations Security Council resolutions criticizing Israel for its actions in the West Bank and Gaza. This February, even as Israel’s far-right government was beginning a huge settlement expansion, the Biden administration reportedly wielded a veto threat to drastically dilute a Security Council resolution that would have condemned settlement growth.

Washington’s response to the International Criminal Court’s efforts to investigate potential Israeli war crimes is equally hostile. Despite lifting sanctions that the Trump administration imposed on I.C.C. officials investigating the United States’s conduct in Afghanistan, the Biden team remains adamantly opposed to any I.C.C. investigation into Israel’s actions.

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, or B.D.S., which was founded in 2005 as a nonviolent alternative to the murderous second intifada and which speaks in the language of human rights and international law, has been similarly stymied, including by many of the same American politicians who celebrated the movement to boycott, divest from and sanction South Africa. Joe Biden, who is proud of his role in passing sanctions against South Africa, has condemned the B.D.S. movement, saying it “too often veers into antisemitism.” About 35 states — some of which once divested state funds from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa — have passed laws or issued executive orders punishing companies that boycott Israel. In many cases, those punishments apply even to businesses that boycott only Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Palestinians have noticed. In the words of Dana El Kurd, a Palestinian American political scientist, “Palestinians have lost faith in the efficacy of nonviolent protest as well as the possible role of the international community.” Mohammed Deif, the commander of Hamas’s military wing, cited this disillusionment during last Saturday’s attack. “In light of the orgy of occupation and its denial of international laws and resolutions, and in light of American and Western support and international silence,” he declared, “we’ve decided to put an end to all this.”

Hamas — and no one else — bears the blame for its sadistic violence. But it can carry out such violence more easily, and with less backlash from ordinary Palestinians, because even many Palestinians who loathe the organization have lost hope that moral strategies can succeed. By treating Israel radically differently from how the United States treated South Africa in the 1980s, American politicians have made it harder for Palestinians to follow the A.N.C.’s ethical path. The Americans who claim to hate Hamas the most have empowered it again and again.

Israelis have just witnessed the greatest one-day loss of Jewish life since the Holocaust. For Palestinians, especially in Gaza, where Israel has now ordered more than one million people in the north to leave their homes, the days to come are likely to bring dislocation and death on a scale that should haunt the conscience of the world. Never in my lifetime have the prospects for justice and peace looked more remote. Yet the work of moral rebuilding must begin. In Israel-Palestine and around the world, pockets of Palestinians and Jews, aided by people of conscience of all backgrounds, must slowly construct networks of trust based on the simple principle that the lives of both Palestinians and Jews are precious and inextricably intertwined.

Israel desperately needs a genuinely Jewish and Palestinian political party, not because it can win power but because it can model a politics based on common liberal democratic values, not tribe. American Jews who rightly hate Hamas but know, in their bones, that Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is profoundly wrong must ask themselves a painful question: What nonviolent forms of Palestinian resistance to oppression will I support? More Palestinians and their supporters must express revulsion at the murder of innocent Israeli Jews and affirm that Palestinian liberation means living equally alongside them in safety and freedom.

From those reckonings, small, beloved communities can be born, and grow. And perhaps one day, when it finally becomes hideously clear that Hamas cannot free Palestinians by murdering children and Israel cannot subdue Gaza, even by razing it to the ground, those communities may become the germ of a mass movement for freedom that astonishes the world, as Black and white South Africans did decades ago. I’m confident I won’t live to see it. No gambler would stake a bet on it happening at all. But what’s the alternative, for those of us whose lives and histories are bound up with that small, ghastly, sacred place?

Like many others who care about the lives of both Palestinians and Jews, I have felt in recent days the greatest despair I have ever known. On Wednesday, a Palestinian friend sent me a note of consolation. She ended it with the words “only together.” Maybe that can be our motto.

Peter Beinart (@PeterBeinart) is a professor of journalism and political science at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York. He is also an editor at large of Jewish Currents and writes The Beinart Notebook, a weekly newsletter.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

A version of this article appears in print on Oct. 15, 2023, Section SR, Page 4 of the New York edition with the headline: The Work of Moral Rebuilding Must Begin Now. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

(Contributed by Michael Kelly, H.W.)

Israeli Airstrikes Have Killed Over 320 Children in Gaza: Health Ministry

A man carries a child, wounded by Israeli airstrikes, into a hospital in Gaza City on October 11, 2023.

(Photo: Mohammed Abed/AFP via Getty Images)

“Where is the outrage we saw when Israeli children were killed?” asked a co-founder of IfNotNow.

Oct 11, 2023 (CommonDreams.org)

Israel’s retaliatory airstrikes across the Gaza Strip after Hamas’ weekend attack have killed at least 1,100 people in the besieged enclave, including 326 children, the Palestinian Ministry of Health said Wednesday.

Gaza-based Hamas launched a major surprise attack against Israel on Saturday, a Jewish holiday, and the Israeli death toll has now surpassed 1,200. The far-right Israeli government and Israel Defense Forces (IDF) responded with Operation Swords of Iron, bombing Gazan residential, medical, and educational buildings, and intensifying a 16-year blockade of the region.

Defense for Children International – Palestine (DCIP), which has documented cases of over 2,400 Palestinian kids killed by Israeli forces and settlers since 2000, has so far confirmed 105 of the 326 deaths.

“Intensive Israeli bombardment throughout the Gaza Strip, lack of electricity, Israeli airstrikes on telecommunications infrastructure, and the unprecedented rate of daily child fatalities has resulted in a lag between confirmed fatalities by DCIP and the overall total child fatalities published regularly by the Ministry of Health in Gaza,” the group said.

Responding to the new Ministry of Health figure, Yonah Lieberman, a co-founder of the American Jewish group IfNotNow, asked on social media, “Where is the outrage we saw when Israeli children were killed?”

DCIP’s Miranda Cleland said that from her time with the organization, she has learned that “all the dead Palestinian babies in Gaza won’t humanize Palestinians to the Israeli war machine, funded by the U.S. government, cheering on their killings.”

GAZA UPDATE: Israeli airstrikes have killed at least 326 Palestinian children in Gaza. @DCIPalestine has been able to confirm 105 Palestinian child fatalities in Gaza, including six-month-old Diaa' Ahmad Abdulati Salah from Jabalia refugee camp. https://t.co/tN3cZtIlE0 pic.twitter.com/4hEEXYNFgD

— Defense for Children (@DCIPalestine) October 11, 2023

The United States gives Israel $3.8 billion in annual military aid under a 10-year deal from 2016. U.S. President Joe Biden said Tuesday that his administration had begun sending additional assistance and he will seek further support from Congress.

The American group Jewish Voice for Peace argued Wednesday that “the U.S. must work to immediately de-escalate to prevent the further loss of life, and not fuel and exacerbate the violence by sending more weapons to Israel. There is only one way to end violence: to address its root cause, 75 years of Israeli military occupation and apartheid. We must end U.S. complicity in this systemic oppression.”

Some members of Congress have spoken out against Israel’s recent killing of Palestinian civilians. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) said Wednesday that while he welcomes the Biden administration’s offer of “solidarity and support to Israel” following Hamas’ deadly attack, “we must also insist on restraint from Israeli forces attacking Gaza and work to secure U.N. humanitarian access.”

“The targeting of civilians is a war crime, no matter who does it. Israel’s blanket denial of food, water, and other necessities to Gaza is a serious violation of international law and will do nothing but harm innocent civilians,” he stressed. “Let us not forget that half of the 2 million people in Gaza are children. Children and innocent people do not deserve to be punished for the acts of Hamas.”

The population of Gaza is about 2 million. Nearly half are children.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) October 11, 2023

Millions of innocent people cannot be made to pay for Hamas’ horror.

Collective punishment is a war crime. So are blockades to food and water.

We cannot allow dehumanization to descend into further atrocity. https://t.co/fRnbV29lVU

Ayed Abu Eqtaish, accountability program director at DCIP, noted Wednesday that the IDF is expected to continue ramping up its operation.

“Israeli forces are destroying entire neighborhoods in the Gaza Strip as an apparent full-scale ground assault is imminent,” he said. “Immediate humanitarian relief is necessary to protect civilians as Israeli forces prepare to intensify attacks and Israeli officials declare their intention to commit further war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is seeking $104 million to provide humanitarian aid across the Gaza Strip and beyond over the next couple of months.

“What is unfolding is already an unprecedented humanitarian tragedy. Whatever the circumstances are, rules apply in times of conflict and this one is no exception. Aid to civilians who have nowhere to flee must be immediate: water, food, medicine,” UNRWA Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini said Wednesday. “It is of utmost urgency that access to humanitarian assistance and protection be upheld for all civilians.”

Catherine Russell, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), this week has also emphasized the necessity of ensuring access to humanitarian aid in the region, along with denouncing all recent attacks on civilians, especially kids.

“I am also deeply concerned about measures to block electricity and prevent food, fuel, and water from entering Gaza, which may put the lives of children at risk,” she said. “I remind all parties that in this war, as in all wars, it is children who suffer first and suffer most.”

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Jessica Corbett is a senior editor and staff writer for Common Dreams.

And from Haaretz.com:

“Anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas,” he told a meeting of his Likud party’s Knesset members in March 2019. “This is part of our strategy – to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.”

–Netanyahu

Seeking a Moral Compass in Gaza’s War

[Note: This an opinion piece by New York Times writer Nicholas Kristof, and does not reflect the editorial opinion of the Bathtub Bulletin. –m.z.]

NICHOLAS KRISTOF

Oct. 11, 2023

Opinion Columnist

The terror attacks by Hamas against civilians who were in their homes and dancing at a concert are being called Israel’s Sept. 11, and that’s a fair comparison.

Let’s hope that Israel responds to this outrage more wisely than we in the United States did to the attack on our country.

There’s a lot of loose talk about eliminating Hamas, and Hamas deserves it. As a journalist who has traveled repeatedly to Gaza, I’m appalled by the sympathy that some Americans and Europeans have shown for a misogynist and repressive terror organization like Hamas. If you care about human rights, you want to see Hamas eliminated.

Yet dismantling terrorist organizations can be harder than it looks and can raise troubling moral questions about collateral damage. The Taliban also deserved elimination, yet in the end it was the United States that was eliminated from Afghanistan. I worry that Israel may charge into Gaza with a ground invasion as thoughtlessly as we plowed into Iraq.

Neal Keny-Guyer, a former chief executive of Mercy Corps, knows Gaza well and thinks it is possible for Israel to kill or capture most Hamas leaders. “But at what cost to civilian lives?” he asked me. He noted that street fighting might well spill over into an uprising in the West Bank and a war on the Lebanon border as well.

Gaza is half the size of New York City and home to some 2.2 million people, almost half of whom are children. Global sympathies are overwhelmingly with Israel in the aftermath of the terror attacks, as they should be, but will that be sustained if a ground invasion leads to thousands of Gazan children dying in house-to-house fighting?

Israelis grieving their dead may not care. The Israeli journalist Haviv Rettig Gur argues that the country has undergone a tectonic shift and is now determined to do what it takes, whatever the cost.

“A safe Israel can spend much time and resources worrying about the humanitarian fallout from a Gaza ground war; a more vulnerable Israel cannot,” he wrote in The Times of Israel on Sunday. Israeli officials have struck a similar tone.

“We are fighting human animals, and we are acting accordingly,” said the Israeli defense minister, Yoav Gallant. Another official was quoted as saying that Gaza would be turned into “a city of tents.”

Rabbi Jonathan Jaffe in Chappaqua, N.Y., issued an open letter noting that Jews have been traumatized by the terror attacks. “Now, Israel will act like any other country would if it was invaded by a bloodthirsty neighbor and its citizens murdered, tortured, kidnapped and mutilated,” he wrote. “And when the world inevitably protests the Jewish use of force, we won’t care.”

I empathize with that trauma and anger. Who can watch the video of Shani Louk, a 22-year-old woman kidnapped by Hamas and paraded half-naked and badly injured in Gaza, and not feel rage?

Yet this mood reminds me of the aftermath of Sept. 11 in the United States, when we sailed into trouble. I wrote column after column warning of the risks of invading Iraq, but Americans brimmed with pain, confidence and resolve. What we needed was a companion dose of humility.

The Middle East is an ongoing education in such humility. Israel originally helped nurture Hamas in Gaza because it thought religious leaders would hang out in the mosque and be less dangerous than nationalist ones. Likewise, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 inadvertently laid the seeds for Hezbollah on the northern border.

There’s a reason that four successive Israeli prime ministers have chosen not to invade and occupy Gaza. Urban combat is a nightmare, whether for Americans in Falluja or Russians in Grozny, and civilian casualties are often enormous. That’s particularly true in a place like Gaza, where civilians cannot flee.

If we owe a moral responsibility to Israeli children, then we owe the same moral responsibility to Palestinian children. Their lives have equal weight. If you care about human life only in Israel or only in Gaza, then you don’t actually care about human life.

What that means in practice is difficult to navigate. Israel has a right to respond, and in war, civilians inevitably suffer.

“Today I woke up to see my neighborhood completely wiped off, including the building where I have my apartment,” Wafa Ulliyan, a Gazan aid worker who immigrated to Canada a few years ago, told me. “It became ashes.”

Ulliyan said she doesn’t want to see either Israelis or Palestinians targeted but just wants two states to live in peace. I’ve met plenty of people like her in Gaza — although of course there are also some who celebrate when rockets targeting Israel go off.

I flinch when I hear the defense minister refer to Palestinians as animals. Hamas dehumanized Israelis, and we must not dehumanize innocent people in Gaza.

There will be no optimal solution in Gaza, any more than there was in Afghanistan or Iraq. We are fated to inhabit a world with more problems than solutions, and it’s fair to feel conflicted about next steps. Israel will face hard choices in the coming weeks; its challenge will be to respond to war crimes without committing war crimes.

We don’t want to replicate in Gaza the approach reportedly expressed by an American Army major in Vietnam in 1968: “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.”

The counsel we Americans should offer Israel is threefold and admittedly difficult to follow. First, Israel has right on its side when it goes after its assailants. Second, urban combat has a poor record in achieving its goals — and a considerable history of horrendous casualties. Third, if your moral compass is attuned to the suffering of only one side, your compass is broken, and so is your humanity.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Nicholas Kristof joined The New York Times in 1984 and has been a columnist since 2001. He has won two Pulitzer Prizes, for his coverage of China and of the genocide in Darfur. You can follow him on Instagram, Facebook and Threads. His forthcoming memoir is “Chasing Hope: A Reporter’s Life.” @NickKristof • Facebook

A version of this article appears in print on , Section A, Page 26 of the New York edition with the headline: Turning Our Moral Compass to Suffering on Both Sides. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

(Contributed by Michael Kelly, H.W.)

THE JEWISH POLITICAL TRADITION DEMANDS SOLIDARITY WITH PALESTINE

Dave Zirin discusses identity and political evolution on his journey to solidarity with Palestinian liberation.

BY MARC STEINER SEPTEMBER 5, 2023 (therealnews.com)

Palestinians gather on the Israeli border to the east of Gaza City, protesting the killing of 11 Palestinians in the raid carried out by the Israeli army in West Bank city of Nablus, on February 23, 2023 in Gaza City, Gaza. Photo by Ali Jadallah/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

In a special crossover moment for The Real News, Dave Zirin of Edge of Sports joins The Marc Steiner Show for an installment of ‘Not In Our Name’—a series of conversations and reflections from the Jewish diaspora on Palestinian liberation. In a meandering conversation, Dave and Marc discuss their own personal journeys through the many sides of Jewish politics and history, the current state of antisemitism in the world of sports, and more.

Studio Production: David Hebden

Post-Production: David Hebden

TRANSCRIPT

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Marc Steiner:

Welcome to The Marc Steiner Show here on The Real News. I’m Marc Steiner. It’s great to have y’all with us. And welcome to another edition of Not in Our Name, our series of conversations with Jews from around the world saying, “No to the occupation of Palestinian Land, and homes, and the ongoing oppression of Palestinians. There is another way.” And today, we hear from this man, Dave Zirin. Now, I’ve known Dave for some years now and he’s been a guest of my show on public radio before. I don’t think ever before here on The Real News, but that’s okay because The Real News now has him here on the edge of sports, which is playing on The Real News.

Dave Zirin writes a column in that name for The Nation magazine. He’s acknowledged around the world as one of the best sports analysts, commentators, and writers, not just covering the games that we play and love, but diving into the social, cultural, and political worlds twirling around and through that world of sports. He’s the author of numerous books, including his latest Game Over, How Politics Has Turned the Sports World Upside Down, and of course, The John Carlos Story, The Sports Moment That Changed the World that won the NAAC Image Award. And let me leave time for our conversation. Dave, welcome. Good to have you with us, man.

Dave Zirin:

Oh, I’m just thrilled to be here and honored. Thank you so much.

Marc Steiner:

Oh, no. I’m looking forward to this. I didn’t know until I thought about having you on this segment, not in our name, that you have been around doing this for a while, talking at conferences, speaking out as a Jewish saying no. Talk about that sojourn for yourself.

Dave Zirin:

No. Absolutely, I was raised in a very Jewish family like so many Jews in the United States. My grandparents and great-grandparents fled to this country from Eastern Europe to flee pogroms like so many Jews in this country. I lack a large family for the reason of the Holocaust. Like so many Jews, the stories of my grandparents, and from what I hear, great-grandparents of the shtetl in which they were raised no longer exist and are even difficult. We had to go through some efforts, even find out the names of said shtetl. Like a lot of Jews, although not all Jews, my grandparents and great-grandparents were very wary about speaking Yiddish in front of me. I would catch them doing it, but they were very insistent on English because they were very one to this idea that America could be a place where they would be safe. And if there’s one thing I’m happy about, when I think of my grandparents, is that they didn’t live to see Charlottesville, that they didn’t live to see the Tree of Life massacre in Pittsburgh.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

I’m actually grateful for that, not just because they led long lives and they would be 115 if they had lived that long, but also because they did have the illusion. And I do think it is an illusion that this country would be safe for the Jewish people, but they had a bigger illusion than that, which was that if the country would not be safe for Jewish people, if that day would come, then they had Israel almost like a place to go where they could be safe in a world built around in their mind, understandably, a history of attempted extermination by dominant cultures that Israel would be able to protect them from that. I grew up with that idea very strongly. I went to Hebrew school where what was taught often was Zionism and supporting Israel more than the Bible and the services and the historical culture. I had a teacher, I’ll never forget an instructor who joked we’re over 5,000 years old as a people, but in this room we’re going to stick to the last 30.

Almost like Judaism is born in 1948 or 1967, that’s where you get Judaism in full until we have our own homeland, how can you really call us a people? I mean, that is something I’ve heard people like Arch Zionists say that it’s almost the negation of Judaism to not have a homeland. Now, I grew up and like yourself, Marc, I found myself very in sync with a more radical set of politics than what was on offer from the Democrats and the Republican Party. Started seeing change as being a product, much more of social movements and individuals rather than in the result of people cutting deals in back rooms on Capitol Hill. And that’s what I dedicated myself to, but I held onto those Zionist ideas. So I would say things like, “I’m against all war, but Israel has the right to defend itself.”

I’m against all nationalisms, although except for I think Israel is really an exception to that, I’m against all nationalisms except nationalisms of oppressed people like Black nationalism. I will always proudly stand with Latinx nationalism, Chicano nationalism. But at the same time… This is such a long answer, is that okay?

Marc Steiner:

That’s cool, man. Listen. Go ahead.

Dave Zirin:

All right. But at the same time I would be like, Israel is the exception. Israel is the exception. And obviously I was always, because I was in these radical circles, I was in debates with Palestinians, with other Jews, with people I respected deeply, people from the Middle East.

Marc Steiner:

This is in your 20s?

Dave Zirin:

Yeah, yeah. Right now when I’m talking to you, I’m between the ages of 18 and 20.

Marc Steiner:

Okay. Right.

Dave Zirin:

My mom is hearing this. She’s going to wish I was in class more, but in college I was doing most of my reading outside the classroom, if I’m being really honest.

Marc Steiner:

I understand that completely. Yes. I got you.

Dave Zirin:

And I was reading, believe me, just wasn’t what I was being told to read. And finally the contradiction just became too great. I want to see liberation for all people, and that means liberation for the Palestinian people. I want to see liberation to the for Jewish people, of course, but I don’t think, certainly not now, I could say I don’t think a right-wing theocracy is an avenue towards liberation. But even in those days when people were hopeful about Rabin, and Arafat, and Oslo, when there was this sense of hope of a two state solution, even then I was like, “I need to reject this and really stand for one state with equal rights for all because a two state solution would be an unequal relationship and further oppression by different means.”

We need to have a South Africa mindset to this, where we have to identify apartheid as apartheid and as consistent anti-racists and anti-oppression activists. We need to take this on. Now, I had Jewish people in my home be like, “Racism, what are you talking about? This isn’t Black and white.” And that only made me more firm in my beliefs because if you can understand historically how the English oppressed the Irish, and if you understand historically that race is just an idiotic construct that’s constructed as a modes of oppression, then I think racism has to be identified as such a dominant feature of Israeli society and one that’s longstanding, and let alone talking about today, where they’re now actually talking actual legislation for different punishments based on your ethnicity and based on your religion.

Marc Steiner:

In Israel at this moment?

Dave Zirin:

Yes.

Marc Steiner:

Right. But there’s new right-wing government.

Dave Zirin:

Yes, exactly.

Marc Steiner:

Fascist government.

Dave Zirin:

Yes. But this fascist government, to me, all it is the fruit from a poison tree. It’s something that has been coming to fruition for some time. And the last thing I’ll say is when people say to me, “Well, what did you read to shape your politics about this?” It’s like, of course I read some of the most famous stuff that’s been out there about this by some of the great anti-Zionist writers, Jewish, and otherwise. And I’ve read some things I’ve disagreed with by people like Norman Finkelstein, for example. But part of me also really respects the way he stuck his neck out there for all these years. But although there are parts of me that disagree with him a lot, but that’s another question. But the real thing that I read that really started to shift me honestly, was the op-ed page of Haaretz, which to a lot of folks in Israel is effectively The New York Times of Israel, for folks who don’t know.

Marc Steiner:

Exactly.

Dave Zirin:

And reading in the op-ed page that they used words that were not allowed to say in the United States like apartheid. That to me-

Marc Steiner:

Referring to Israel as an apartheid place?

Dave Zirin:

Referring to Israel as apartheid place and talking about a Jewish writers speaking about that openly and what the responsibility is of Jews in that context, that to me was just like, “Okay. There’s justice and injustice in this case. This is straight up a which side are you on question.” We can’t straddle the middle on this. And that made me a fighter for Palestinian liberation, which I’ve proudly been in the decade since.

Marc Steiner:

A lot of things popped in my head as you were speaking. And I was thinking about this poster that I got in Cuba in 1968 when I went there for the first time. And the poster was a picture, a drawing of the entire state of Israel, Palestine as one. And it said, “One state, two peoples, three faiths,” suppose where I still have hanging in my study.

Dave Zirin:

That’s beautiful.

Marc Steiner:

And it struck me because, at that point, I really newly minted against Zionism, Israeli state after, as I told you before in the air that thinking about volunteering for the Israeli army to fight in the ’67 war.

Dave Zirin:

When you said that… I jump in real quick-

Marc Steiner:

Yeah, sure. Go ahead, man.

Dave Zirin:

… because this speaks to when you came of age. I once had someone tell me this amazing story, and this just says something about why a lot of Jewish people feel a great deal of confusion on some of these questions. I think that their synagogue in 1964 gave a youth, their youth group had the option to go on the Freedom Riders or go to Israel and work in a kibbutz or something of that nature. And it’s just so interesting to me that they saw no contradiction on that whatsoever.

Marc Steiner:

None. All none.

Dave Zirin:

I mean, none.

Marc Steiner:

You talk about the Freedom Riders, we don’t want to digress too deeply into this, but 70% of the white Freedom Riders were Jews.

Dave Zirin:

Yes. Wow. Which speaks to a lot of the right-wing, and we don’t talk about this nearly enough, but a lot of antisemitism from the right about the ’60s movements, SDS, et cetera.

Marc Steiner:

So let me ask you this difficult question.

Dave Zirin:

Sorry.

Marc Steiner:

No, you just raised it. You’ve spoken about this. I’ve seen at some of the conferences you’ve been to and things you’ve written, and the quote you had at the beginning of our discussion today, the right-wing Christian nationalist movement in this country, which is hugely powerful and is seizing power across this country right now, really dangerous for our future. They are at the same time they are anti-Semitic, they are pro-Israel. And so it creates this real confusion. And let me add to that something even more difficult to me in some levels, you have these conversations you’ve had with a number of people, like with Michael Bennett, and we’ll talk about that man. And Kyrie Irving, and it also goes into this difficult area of Jewish racism and Black antisemitism. They both exist and it complicates this struggle. Both those things. Talk a bit about your thoughts around that and how we navigate ourselves through that.

Dave Zirin:

Absolutely. The starting point is asking the question of navigation of a very difficult question. And that navigation begins with history. So the history between Black people and Jewish people in the United States is extremely complicated, extremely multilayered, and has been written about in great detail by authors. Both Jewish and Black have pondered this from, of course, James Baldwin, Richard Wright. I mean, there’s a real pondering of what do we make of Jews? Are they our comrades in struggle or not? And one of the things, and of course much has been written by Jews of all stripes about how do we work with Black people? How do we fight racism? Why do we feel like it’s an obligation to fight racism?

Like what you mentioned about the percentage of Jews involved in the Freedom Rides. I mean, that comes from a faith that says we need to stand with Black people. But that’s only one side of that tradition. And that tradition is important though because the other side, and I’m going to surprise you with what I say the other side is I think, the other side, which doesn’t get talked about nearly enough, is that Black people have put their lives on the line fighting fascism since the 1930s-

Marc Steiner:

Easily, yes.

Dave Zirin:

… 1920s, even with the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini. And that’s never talked about. I feel sometimes that, particularly Jewish liberals are like, “Why don’t you support us to the Black community? We have fought for you for so long, not with you, but for you.”

Marc Steiner:

For you, which is a whole different concept.

Dave Zirin:

Whole different concept. It’s like you owe me something. And I feel like, “Wait a minute, do you realize that Black people died in Spain fighting the Spanish Civil War to keep Franco from taking power?” I mean, they put themselves on the line against international fascism time and again. Not to mention you think of people like Paul Robeson taking a stand against McCarthyism, which was a wholeheartedly anti-Semitic institution among anti… just about everything institution. So I think that part of the history needs to be known. The other part of the history, which I know you’re familiar with, Marc, but just saying it for-

Marc Steiner:

No. Please, go ahead.

Dave Zirin:

… the listeners out there, is you have to deal with the economic basis of the cities of the United States to understand the tension, and you have to understand whiteness, and what I refer to sometimes as conditional whiteness. Jewish people in the cities striving, attempting to make it in this country. Strong emphasis on community and education, strong emphasis on rising, and a strong emphasis on patriotism as well. Eventually leaving the inner city, setting up camp in wealthier, more affluent neighborhoods, or even just neighborhoods that are not so people living on top of each other, housing projects and the like, but they’re still owning a lot of the local businesses and running a lot of the local businesses.

And then Black people, the great migration coming up from the south, living in cities. So if you are Black and living in a city a hundred years ago and you feel generally screwed over by society, who is the face of society that you see every day, it’s not somebody running a Wall Street bank. It’s not somebody in the Oval Office. It’s the person you see every day at the local store, every day at the cleaners, every day, what have you. And on the other side of the law, who is running the numbers in places like Harlem, who’s got the power? There’s the local guy, but then there’s the man. And the Jewish mafia was very real at that time.

Marc Steiner:

I knew them well. Yes, they’re [inaudible 00:16:04].

Dave Zirin: