The nineteenth century was a watershed for western civilisation. It was, for Nietzsche, the beginning of a great crisis for mankind.

Secularism spread rapidly across Europe but there was nothing to fill the void that religion had left.

The sciences, that had been so preoccupied with physics and cosmology in the centuries before, had suddenly begun to systematise life itself. Halfway through the century, evolutionists broke the news that human beings were likely the descendants of apes.

It is against this backdrop that Nietzsche proclaimed: “God is Dead. We have killed Him.”

The upshot of this, according to Nietzsche, was nihilism: a spiritual sickness in which we have become bereft of purpose and meaning.

But Nietzsche is the great psychologist-philosopher, a man who had a profound understanding of what it was to be human. He believed he had the antidote for our psychological ills, both as individuals and as a civilisation.

When Nietzsche set about curing our ills he asked the most fundamental question:

What is driving us?

Firstly, to be driven is to change. Nietzsche believed that the idea of “becoming” should take precedence over the idea of “being”. In ancient Greece, two schools of thought emerged regarding the nature of the universe. While Parmenides believed change to be an illusion, Heraclitus of Ephesus reasoned that the only constant thing in the world is change.

“All entities move and nothing remain still […] You cannot step in the same river twice.”

To Heraclitus, the world is an “eternal fire”:

“ This world, which is the same for all, no one of gods or men has made. But it always was and will be: an ever-living fire, with measures of it kindling, and measures going out.”

We only have fragments of Heraclitus’s wisdom saved for posterity in the writings of later philosophers like Plato. What little there is of Heraclitus’ words impressed themselves immensely on Nietzsche.

The philosopher agreed with Heraclitus that the world is constantly changing and that fact is all that we can really be sure of.

While Heraclitus conceived of the fundamental substance of change to be fire, Nietzsche thought along more modern lines. The philosopher believed the fundamental engine of change to be “The Will to Power” (“Wille zur Macht”).

The Will to Power

For Nietzsche, this fundamental driving force was the “unexhausted procreative will of life” in all things. In the 1880s when Nietzsche wrote most frequently about the Will to Power, a number of sciences and philosophies were emerging that sought a general principle of what actually drives people, or even living things as a whole.

Psychoanalysis gave us the pleasure principle, Evolutionism gave us survival, Utilitarianism gave us happiness, and Marxism gave us an overarching narrative of class struggle. All of these sciences or philosophies built an explanation of human behaviour on these basic principles.

One of Nietzsche’s most eminent influences, Arthur Schopenhauer, posited the idea of the “Will to Life” as the driving force of all living things. This was close to the idea of Darwinian evolution’s principle of natural selection. Power, according to these theories, was simply a means to survival.

But Nietzsche believed power to be the ends of all effort. This is explained by behaviour that contradicts survival instincts. Many organisms, particularly human beings, risk death to flourish.

Nietzsche broadly accepted the theory of evolution but disputed its purpose. At one point (in his book The Twilight of the Idols), he called himself the “anti-Darwin”, because he felt so strongly that self-preservation wasn’t man’s primary drive. Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil:

“Physiologists should think twice before positioning the drive for self-preservation as the cardinal drive of an organic being. Above all, a living thing wants to discharge its strength — life itself is will to power: self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most infrequent consequences of this.”

Nietzsche went as far as claiming the Will to Power was a fundamental metaphysical truth about the universe, not just an explanation for the behaviour of people. “World is the will to power — and nothing besides!”

The idea of the Will to Power has been widely misunderstood. It is one of the most controversial aspects of Nietzsche’s philosophy. Many have assumed that the philosopher is applauding the characteristics of the brute or the sociopath.

Part of the reason for this is because the Nazis reinterpreted the idea to mean power as domination. The philosopher’s sister, Elizabeth, the custodian of his writings after his death, was a Nazi sympathiser and an anti-semite. (Nietzsche himself thought racism to be stupid and aligned himself with no political programme.)

The Nazis glorified the Aryan militarist and authoritarian at the apex of the racial hierarchy. This distortion of Nietzsche’s ideas stuck until the philosopher’s reputation was resuscitated in the 1960s.

In some passages, Nietzsche does indeed accommodate the idea that some “races” have acted as predators or “blond beasts” — by this Nietzsche was evoking the lion (with its characteristic blond mane) — in their preying of other peoples and cannot really be blamed for doing so.

This historical generalisation (that is admittedly unpalatable by today’s standards) was merely used to underscore the existence of the Will to Power. It was interpreted by the Nazis to mean the Aryan race as typified by northern European blond peoples.

The Nazi idea had little resemblance to what the philosopher meant. “Power” in the way Nietzsche used the word, on the whole, has more to do with growth than domination; more about power over the self than power over others.

Power is intrinsic to his idea of self-overcoming. The problem is that power does not drive us as individuals. Power as a general principle drives everything. That means that ideas and biological systems even at a cellular level have within them the Will to Power.

The human being is a zone of competing drives and ideas that often contradict one another. Here’s a very simple example: you may have the urge to eat that sugar-glazed doughnut with creme inside and chocolate sprinkles, but you also have the drive to keep your weight down.

Ideas are the same. We have many competing ideas in our psyche about morality or what the world is like. We often do things that we come to regret, and we change our minds constantly. This is why human beings are so complicated.

Nietzsche’s second step to Self-overcoming is to examine ourselves. We must ask ourselves two questions: What are all these competing drives in our psyche? And where did they come from?

Genealogy of Our Morals

One of Nietzsche’s most innovative contributions to philosophy was to look at the past in order to diagnose contemporary attitudes and dogmas of morality. He wrote The Genealogy of Morals to investigate the origins of Western values that he felt had caused a spiritual sickness in western society.

The principles of The Genealogy of Morals can be applied to your own belief system. If you examine your own history (and indeed history before you existed), you’ll find that your values are derivatives from the values of others.

“Direct self observation is not nearly sufficient for us to know ourselves: we need history, for the past flows on within us in a hundred waves.”

We cannot untangle ourselves from the past. Self-mastery requires us to understand how it has shaped our circumstances, our attitudes, beliefs and our values.

When we understand how enmeshed we are in the attitudes and beliefs handed down to us, we can begin to untangle ourselves and start to think about what we really value.

This would allow us to start to understand the conflicting drives within us. Nietzsche warns us that this is not an easy process, to peel away the layers of the psyche is to open old wounds and to experience hard truths.

But the Will to Power manifests itself in so many subtle ways, and it’s difficult to know what we should channel our power to.

Nietzsche believed that the universe has no inherent meaning. It is up to us as individuals to find meaning and purpose in an otherwise meaningless world. In short, you need passion.

You must have the need to be powerful, otherwise you will never become powerful. All those inherited and contradictory drives and your instincts will take precedence in your psyche. Nietzsche wrote in his philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “He who cannot obey himself will be commanded.”

But if you have passions, the Will to Power will be channelled into them. In other words: you can harness the Will to Power.

Your passions will lead you to obstacles and resistance, but that, to Nietzsche, is a good thing. Overcoming resistance is gaining strength. Just as lifting weights build muscle, the problems we face when we follow our passions will make us grow and flourish as individuals.

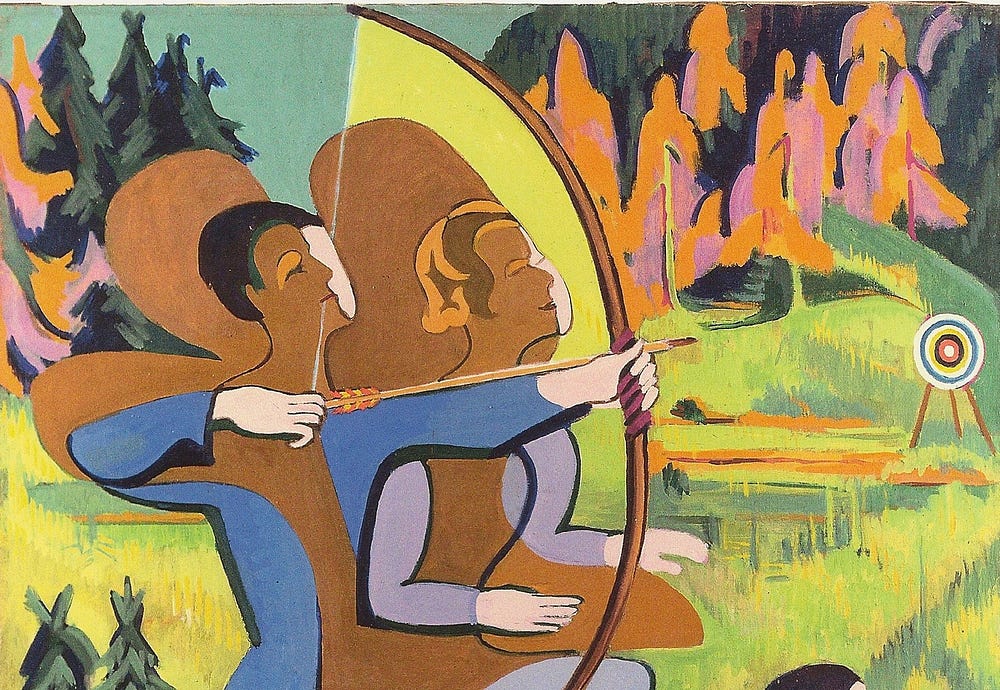

Heraclitus wrote that “there is harmony in the bending back, as in the bow or the lyre.” The tension of the bowstring is necessary to shoot the arrow, the lyre string to play the note. The opposition of forces — the effort — is required to create the effect. “All things come into being by a conflict of opposites,” Heraclitus wrote.

So what does the human being who has overcome their self look like? Nietzsche wrote a great deal about this. He presented his readers with an ideal. He set a goal of a greatness that humanity must somehow meet. That goal was the “Overman”.

The Overman

Nietzsche introduces the idea of the Overman (Übermensch) in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1886). The Overman is presented as an ideal human being that is not yet realised. (It’s worth noting that “mensch” does not specifically mean “man”, but “human being” and so the concept is not an exclusively male one).

Nietzsche draws from the science of evolution, comparing man to the potential Overman, as an “embarrassment” in the way the “ape is an embarrassment to man.” Mankind as a transitory phase:

“Man is a rope, tied between beast and overman–a rope over an abyss. What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end: what can be loved in man is that he is an overture and a going under.”

The Overman is not a physical evolution of man, but rather a spiritual evolution. The process is not determined and Nietzsche feared that the Overman’s time may not come if we do not have the courage for self-overcoming.

“one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star. I say unto you: you still have chaos in yourselves. Alas, the time is coming when man will no longer give birth to a star. Alas, the time of the most despicable man is coming, he that is no longer able to despise himself.”

The “dancing star” the philosopher refers to is the Overman. He feared that the nihilism of the modern world was giving rise to what he called the “Last Man” the lazy nihilist who only seeks contentment. The Overman, in contrast, would risk everything to overcome himself.

Nietzsche mentioned a few in history who he felt came close to being Overmen. Napoleon and Goethe are examples he goes back to often. Napoleon was the amoral conquerer who risked his life (many times) for the glory of his own imperial state.

Goethe was the great polymath, one of the most accomplished writers in history, who also contributed enormously to scientific and philosophical fields.

Both these men were almost Overmen, but not quite. Perhaps the Overman is an impossible goal for a person like a utopia is for a place. The point of the Overman is to set in place an ideal that is opposed to the common ideals of moral virtue. To Nietzsche, these ideals are negative, they stop people from mastering their own selves.

Negativity

Nietzsche found two causes of negativity that hold people back from embracing self-overcoming: self-preservation and the hope for a better life after death.

For Nietzsche, the promise of heaven as a reward for meek and humble behaviour in this life was a terrible waste. The earthly realm is our one shot at life and we must make the most of it. Self-overcoming — for whatever purpose we give ourselves — is the greater meaning of our lives. He wrote:

“The overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the overman shall be the meaning of the earth! I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes! Poison-mixers are they, whether they know it or not. Despisers of life are they, decaying and poisoned themselves, of whom the earth is weary: so let them go.”

If this is uncomfortable reading for some people, Nietzsche would reply that we should emanate goodness and positivity from who we are, not for a reward of eternal life. If we behave well for a reward, we’re not really behaving with integrity.

Self-preservation is also counter to self-overcoming. As has already been covered, the Will-to-Power transcends the Will-to-Survive. Many living things risk literally everything they have to grow.

Those who choose easy contentment and material happiness will never come close to achieving the exuberance of the Overman. The secret to finding true happiness, as far as Nietzsche presents it — to rejoice in one’s strength and exuberance — is to risk happiness.

As reckless as that sounds, it perhaps is the antidote to the modern epidemic of nihilism.

Thank you for reading, I hope you learned something new.

WRITTEN BY